Jazz Fest: How New Orleans is Jazz Fest, Pt. 3

Now that we've looked at the numbers, what do we do with that information?

Mardi Gras is the source from which all things flow in New Orleans, and Jazz Fest is perhaps its most important product. For that reason, conversations about Jazz Fest are almost always conversations about New Orleans as well. Anxieties about change in one reflect anxieties about change in the other.

When you look at Jazz Fest schedule changes over the years, it’s easy to see why some think it has changed in a meaningful way. With its “jazz and heritage” orientation, Jazz Fest has been a home for those who love “real music,” and Festival Productions has booked artists whose work embraced classic musical values—good singing, good playing. The marketplace’s focus on popularity didn’t seem to be a concern at Jazz Fest, where well-known and lesser-known bands played sets of similar lengths, and artists from New Orleans who didn’t sell (by national standards) headlined with the few performers booked who did. Outside of New Orleans, The Neville Brothers were a mystery. How could they be so good and not sell? At Jazz Fest, they were heroes, and great, eccentric talents such as Professor Longhair, Snooks Eaglin, James Booker, Earl King, and Eddie Bo were similarly revered.

A similar tension exists in numerous genres, particularly Americana, where for a long time fans of the genre defined the music by what it wasn’t—contemporary, suburban Nashville country—than by what it was. But people battling the “real music” question in other genres don’t have their civic identity threatened by the outcome. Whatever battle for the soul of jazz that is likely being waged somewhere doesn’t affect residents of New York, Boston, or Philadelphia. Because of the intensity of our identification with our musicians, if New Orleans music loses, we lose.

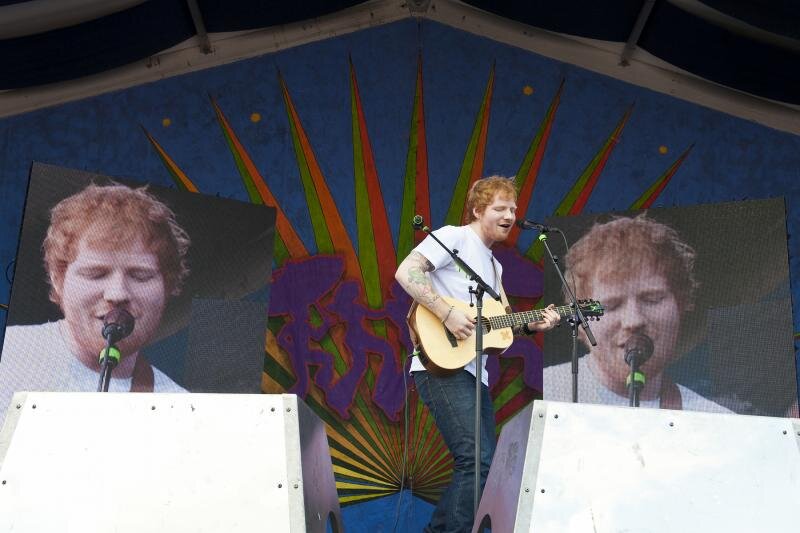

The shift reflected in larger touring acts getting longer spans of time has made Jazz Fest look depressingly familiar. The music marketplace values that affect media coverage and radio play—values that have excluded artists from New Orleans for decades—seemed to have greater sway over the festival than they once did. New Orleanians once again get respect, praise, and token attention while national and international stars get prime time and prime time money. Bon Jovi can be big everywhere; do they have to be big at Jazz Fest too? Is there no Bon Jovi-free zone?

It doesn’t help that the Festival Productions/AEG Live partnership that made this change possible started in 2004, the year before Hurricane Katrina. The helplessness we felt as decisions about the city’s future were out of our hands is also felt by those sorry to see the changes to Jazz Fest but unable to do anything about it. The changes also come at least partly from forces beyond our control.

Jazz Fest producer Quint Davis has quoted Mayor Mitch Landrieu on a number of occasions as having said after Katrina, “Not having Jazz Fest is not an option.” It’s unlikely Landrieu said that solely out of concern for the well-being of music lovers. New Orleans’ shift toward a tourism-based economy was already well underway, and the mayor knew how devastating it would be for one of the bedrock events of the city’s tourist trade to skip a year. Famously, money made during Jazz Fest helps clubs, restaurants, and businesses get through the summer, and with that in mind, it's hard to imagine that civic leaders see any problem with giving two or more hours over to the Boss or Rod Stewart or Fleetwood Mac. At least then there would be somebody they know at the Fair Grounds.

Yesterday I asked who would headline the main stages these days if not touring bands. Who’s big enough locally to close the Acura, Gentilly, and Congo Square stages? It’s tempting to take the question as an indictment of New Orleans, but it’s likely a national issue. As the monoculture fragmented through the ‘80s and ‘90s, the lines of transmission that could connect genuinely mass audiences came down. The other major summer festivals including Voodoo—the season ender—deal with a version of the same question because there few acts from the last 10-15 years who can reliably deliver festival headliner crowds. It’s not a New Orleans problem; it’s a 21st Century problem.

When I’ve asked the headliner question online, there are always people who suggest cutting those headliners and making a smaller festival. Make the festival more intimate like it used to be. That’s easier said than done. It’s likely that the value of Jazz Fest’s sponsorships are tied at some level to attendance and the number of people who will see, hear and use the sponsor’s name, so a smaller festival would not only mean reduced revenue from ticket sales but reduced revenue from sponsorships, food tents and craft tents. Potential revenue decreases of that size would be hard on the festival as a whole, not only its ability to book million-dollar acts.

Jazz Fest has also become part of the national music festival conversation, so changes to its headliners would affect national interest in the festival. It is talked about along with Coachella, Bonnaroo—which was recently sold to Live Nation—and Lollapalooza, and reduced star power wouldn’t affect those for whom Jazz Fest is an annual chance to reconnect to New Orleans music. Those who plan summer trips to festivals, on the other hand, make decisions based on lineups would likely find a primarily NO/LA lineup less appealing.

If people want a NO/LA-first festival, one already exists. It’s called French Quarter Festival and it’s free. Jazz Fest is in an interesting spot as it doesn’t have as many slots available for out-of-town artists as the other major festivals, nor does it have as big a budget because its ticket is affordable by comparison. At the same time, the free French Quarter Fest has doubled down on Jazz Fest’s core constituency. It’s hard to imagine the festival’s critics feel for the bind Jazz Fest is in, but it’s equally hard to imagine that the market could bear two similar festivals, or that it would work out well for the one that has to charge admission.

Peeling a layer of star talent isn’t any more practical than trying to roll back the clock. If Festival Productions wanted to address the perception that New Orleans and Louisiana bands are the warm-up acts for the superstar headliners, it could adjust the set lengths so that they’re more equal, but entirely reining in headliners’ set lengths carries its own problems. Bruce Springsteen hasn’t played New Orleans since I moved here in 1988 except at Jazz Fest. Neither has The Who or No Doubt. If I’m a fan of these bands, I want to see the show fans in other cities see, and I wouldn’t understand why the set had to be truncated to make happy bands I could see every month if not every week. Out-of-town music fans may come for the local bands, but a lot of local fans are motivated by the bands they can’t see.

That, it seems to me, gets to the heart of the anxiety expressed about Jazz Fest. It has changed in meaningful ways, but not in the ways people often fear. In the years we studied, ranging from 1992 to 2015, pop headliners grew in number, and while the stretch to fit them under the “jazz and heritage” rubric has often strained credulity, some can’t be made to fit. The Strokes and Phoenix were interesting bookings, but they were simply from a different musical world. Their audiences didn’t stand apart from Jazz Fest regulars, in the case of The Strokes because their fans didn’t appear to show up. When Phish played in 1996, their fans shocked the faithful with their seeming disregard for the neighborhood, the Fair Grounds, and others. People tell horror stories of Phish fans buying food then sitting down in front of the booth to eat it, blocking the way for others.

As much as other bands may be a problem, it’s often their fans who are the breaking point. Dr. John fans were understandably incensed that Bon Jovi fans booed him, and Irma Thomas has had to deal with unruly crowds tired of waiting for the headliner.

It’s bad enough to have music you don’t like on a stage a New Orleanian could play, but disruptive fans are something bigger. They change the nature of the festival, so what was once an annual rendezvous of the faithful where people shared musical and likely cultural values has becom so diverse in its appeal that you can’t make any assumptions about the person next to you. I wonder if for critics of Jazz Fest, this is the core problem—that it’s no longer a gathering of the tribe, and Phish's appearance brought a clash of their tribe versus Jazz Fest's. New Orleans and its artists aren’t just ours anymore. The city and its music aren’t America’s best kept secrets anymore. This dynamic has played out in the culture-related skirmishes that have taken place in the last five years, and questions about New Orleans’ identity underlie many conversations.

Those who want New Orleans and Jazz Fest to once again be their private concern are going to be disappointed. Neither is happening. I often wonder if the desire for the better days is also a manifestation of the baby boomers’ in Jazz Fest’s audience wanting to roll back their own clocks as well, or at least get back to a simpler time when they knew all the bands, were the cool kids, and had smaller crowds to be cool in.

But the reassuring takeaway is that despite the anxiety, New Orleans’ culture continues to find ways to reassert itself for its context, and it continues to find audiences. I’d feel worse about the state of things if I saw locals playing to empty stages, but they’re not. And there were reasons other than the Acura Stage why those I saw playing less attended shows didn’t draw.

Jazz Fest is such a complex phenomenon that we can and should keep chewing on it to understand its place and influence in New Orleans. It has committed its share of sins, but on the question of how New Orleans it is, the math says not as much as it once was, but by degrees.

Thanks to Lauren Keenan, Cara Lahr, Justin Picard, Karina Aquino, Will Halnon, Brian Sibille and Amie Marvel for all their help making this piece possible.

How New Orleans is Jazz Fest, Part I

How New Orleans is Jazz Fest, Part II