Jazz Fest: How New Orleans is Jazz Fest - A Coda

Some final thoughts on our examination of Jazz Fest schedules to assess the ongoing relationship between the festival and the New Orleans music community. Where do we go from here?

[Updated] Jazz Fest 2015 is over, and the approximately 460,000 people made it the best-attended post-Katrina Jazz Fest but still nowhere near 2001’s 650,000. During the festival, we ran a three-part series examining lineup and schedule changes over the years, and we found that the festival actually presents more New Orleans and Louisiana talent than ever because it presents more talent period—180 more artists between 1992 and 2015. At the same time, the percentage of New Orleans and Louisiana acts remained roughly the same as part of the overall talent pool.

But we did see signs of change for New Orleans and Louisiana artists. Once, most of the acts played sets of similar lengths regardless of popularity, talent, or length of career, but recent lineups have been stratified, with more and more national acts playing longer, higher profile sets. In 1992, the New Orleans Musicians' Alumni Association played a two-hour set on the Lagniappe Stage. After that, the longest set was 80 minutes and seven artists played shows that long—Neville Brothers, The Radiators, CJ Chenier, Illinois Jacquet, Dr. John, Huey Lewis and the News, and Bobby Cure and the Summertime Blues. This year, 22 acts were scheduled to play shows 85 minutes long or more, and five had shows two hours’ long or more. Only two of those acts were by regional bands, with Brass Bed and The Voice of the Wetland All-Stars playing 85 minutes. How long someone gets to play isn’t a precise barometer of value, but the lack of proportion creates the appearance that local artists are the opening acts for national headliners, particularly on the Acura, Gentilly, and Congo Square stages.

My take is that the anxiety over the New Orleans-ness of Jazz Fest reflects a concern that Jazz Fest no longer belongs to its true believers, and that it is no longer a gathering of their people nor a reflection of their values. Or, that it reflects them and their interests less strongly than it once did.

Saturday’s crowd plays into that narrative. When the size of the audience makes jumping from stage to stage and food booth to food booth prohibitively difficult, the crowd is too big for Jazz Fest to be Jazz Fest—record or not. A crowd that swamps the Fair Grounds for hours plays into the idea that Jazz Fest is just about the money.

Since we ran our story, people have suggested new studies to help get at similar questions, and I think more data-driven examinations of the festival are in order. Memories, anecdotes and incorrect suppositions have become such a part of our Jazz Fest conversation that grounding it in math helps to stabilize discussions that can easily become wobbly with emotion and wrongly drawn conclusions treated like fact. Our study used stats as an attention-getter and to start a conversation, but we were limited by manpower and time as to how far we could go. We took data snapshots to get some insight, but a more complete look would certainly tell the story more precisely. Someone who can do better than an english major’s math will produce stronger data.

One study I’d love to see would put ticket prices in perspective although, admittedly, it’s not an issue I connect to. People grouse that tickets are too expensive to go every day anymore, but it was too expensive for me to go everyday in the early ’90s when our study began. I’ve never felt so flush that I could afford more than two or three days per festival, so my intuition says the question is more complex than simply one of price points. Perhaps if someone looks at the rising ticket prices in contrast to the wages and other expenses of likely festgoers, we’d get a better sense of the effect of ticket prices. Could it be that this year’s $58 in advance/$70 at the door would be more easily spent by the average festgoer if he/she was a college student with mom and dad helping with the overhead, or a renter with no mortgage, no kids, and few of the expenses that come with maturity? One musician told me his African-American neighbors could no longer afford to go for even a day, but he conceded, “They tend to regard it as an expensive, out-of-town white people thing that isn't of much interest to them,” and that they’d be unlikely to go if the festival was free. That suggests values are a part of the conversation, and that other priorities also affect ticket purchases.

Alec Vance of Chef Menteur shared a chart he did in a Facebook conversation that shows the steep climb in ticket prices. Graph wages, tickets as a percentage of household expenses, and comparative festival ticket prices on to that we have the start of a better understanding of that annual hot button issue. It would also be interesting to track changes in the festival’s demographics. Who’s buying the tickets? Is it an out-of-town white person thing? Can we know more exactly whose thing Jazz Fest is?

Another study I’d love to see done that more directly connects to ours is an examination of the talent payroll to see what story that tells. We can talk about placement on the schedule, on the promotional materials, and the time allotted each performer, but money is a signifier that we all understand of how valued someone or something is. I fear that in recent years, the story the payroll tells has been an ugly one, and that Jazz Fest has its own small-but-growing class of One Percenters, and that the sort of economic disparity we see in society is playing out at Jazz Fest as well. Million dollar contracts may be the cost of doing business with some acts, but if wages go up at the top without movement upward as well in the lower ranks, it’s going to be hard to get music fans and musicians to feel the festival’s love.

I suspect--This is at least the second or third supposition in this section. To be clear, I’m spitballing--that the festival would say that part of the compensation for playing Jazz Fest is exposure, and it would be right. While I was at OffBeat, we regularly heard from fans of New Orleans music from around the world, and many of the bands they loved they first heard at Jazz Fest. A circuit of clubs and festivals has developed around the country that give local artists a place to play, and many of their bookers first heard bands at Jazz Fest. Fans of The Who or Keith Urban show up, camp out, hear whoever’s on in front of them, and theoretically a percentage of them become fans as well.

With that in mind, another good study would be to discover the actual economic impact Jazz Fest has on an artist. What is the dollar value of exposure? Whatever it turns out to be, Jazz Fest will have a hard times making people believe that the festival is on the side of the musicians if the paycheck disparity is too great.

In our study, I suggested that we question the long-held belief that business done during Jazz Fest gets businesses through slow New Orleans’ summers. Another related one would be the economic impact of Jazz Fest on musicians. When I looked into whether or not musicians would get paid for a rained-out day in 2004 for Gambit, many musicians were reluctant to talk to me on the record because their economic year relied too heavily on a good Jazz Fest for them to be comfortable expressing their concerns about getting paid. They feared that speaking out would get them blackballed, and the time the 10 or so days of Jazz Fest were the biggest for album sales for artists playing the festival. Is that still the case? What other income comes as a result of Jazz Fest?

I genuinely believe Quint Davis and the staff of Jazz Fest are true believers who value New Orleans and its musicians. Davis often seems happiest when he’s talking about musicians, and while he can be guarded when talking about the festival, he has been giving of his time and candor to talk about the musicians who helped shape his life, the festival, and New Orleans’ music. His openness with journalists when talking about Bo Dollis has been invaluable for helping people assess his importance.

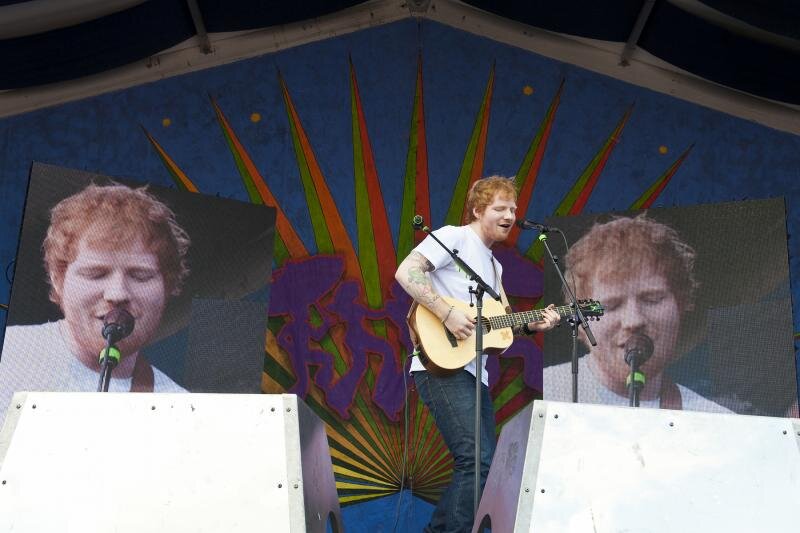

But I don’t think they’ve been hoodwinked or shanghaied by AEG Live or any of Jazz Fest’s sponsors. Festival Productions has made business choices dictated in part by the marketplace and in part by what they perceive as best for the festival’s long-term health. Bigger festivals are likely in Festival Productions’ best financial interests, and city leaders see it as in theirs as well. The throng that descended on the Fair Grounds for Elton John, Ed Sheeran and TI had to sleep somewhere and pay someone’s hotel tax, as well as eat in someone’s restaurant and drink in someone’s bar. True believers who want the festival they believed in and connected to can complain, but happy and sad tourist dollars spend the same. And, to be fair, once the last sets started on Saturday and the crowds got where they were going, the people at those shows were very happy with what they saw.

Also, to be fair, the crowd was not entirely from out of town. “I think New Orleans wants the best festival in America, the best festival in the world, the best festival they can get, talent-wise,” festival director Quint Davis told Nola.com’s Keith Spera, and there’s a lot of truth in that. Long-time devotees of New Orleans’ music may disagree, but those who only see live New Orleans music for a day during French Quarter Fest and a day at Jazz Fest likely find the festival more exciting now than it has ever been. For them, Elton John and Sheeran weren’t causes for anxiety but celebration. Again, the festival’s long-time core audience sees a Jazz Fest that’s no longer a gathering of the tribe, but a larger audience may be developing a stronger connection to the festival than it had for years. A study of attitudes toward Jazz Fest correlated with how much New Orleans music attendees see in clubs during the rest of the year would likely tell us a lot.

Some economic disparity is inevitable when The Who and Elton John are in the mix and the biggest-drawing New Orleans acts may be Dr. John and Trombone Shorty, but some of that disparity has always been in the festival. Still, there comes a point where We love you, we’re paying you the same, you’re playing at 2 can be easily confused with Piss off.

Finally, today at Nola.com, festival executive director Quint Davis talks about the crowds with Keith Spera and he sees the problem not as one of numbers but of space, and targets the chairs and blankets. That makes sense, though it opens another set of questions. The interview is worth reading because Davis is usually pretty frank with Spera, and if you don’t read him cynically, there’s a lot to be learned. You may not agree with him, but you get a clearer sense of the thinking that shapes Jazz Fest.

How New Orleans is Jazz Fest Pt. 1

How New Orleans is Jazz Fest Pt. 2

How New Orleans is Jazz Fest Pt. 3

Updated 2:30 p.m.

The WWL video was added after initial publication.