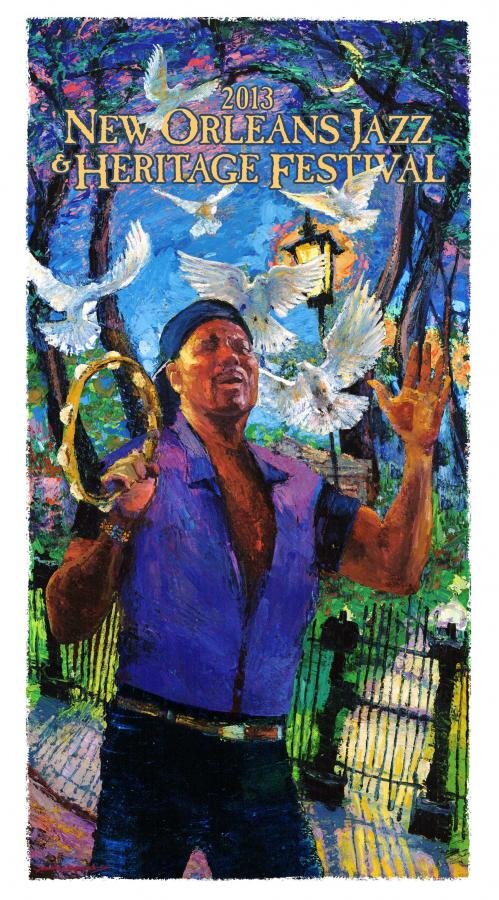

Jazz Fest: How New Orleans is Jazz Fest?

It has become a ritual to complain about the festival not being about New Orleans anymore. Is there any truth to that?

There was a time when the Jazz Fest lineup announcement was met with complaints over opportunities missed. Why weren't seemingly appropriate new bands included? When asked in 1994 if The Black Crowes and Counting Crows should be a part of Jazz Fest, producer Quint Davis said, “I think Counting Crows and Black Crowes and Pearl Crows and Nirvana-Crows and Screaming Crows and every single one of them should be at this festival, but not on the stage.”

In the early 2000s, Counting Crows lead singer Adam Duritz followed Davis’ prescription and regularly attended the festival as a civilian, and it must have worked because Counting Crows played Jazz Fest in 2002 and 2007. The Black Crowes played it in 2005, though it’s unclear whether either Robinson brother put in time in the Jazz Fest audience, and if he learned a thing while there.

It's understandable if festival organizers wonder what it takes to make people happy because in recent years, a new complaint now meets the arrival of the Jazz Fest lineup each year: Where are the locals? Big ticket, out of town talent loosely connected to “jazz and heritage” creates the narrative, rightly or wrongly, that Jazz Fest has lost its way, particularly when combined with the equally ritualized complaints about ticket prices. The anxiety is heightened by the ambient concern over gentrification and the changing place that musicians and fans feel in post-Katrina New Orleans. Is Jazz Fest one more place where New Orleans’ culture is getting nudged aside by out-of-towners?

Concerns about Jazz Fest losing its identity is partly a social media phenomenon. On the day that Jazz Fest rejection letters go out, many of the artists who once had to bear the bad news privately can now share their disappointment with online friends and family. The sad Facebook posts stack up and further feed the narrative that Jazz Fest isn't what it used to be, particularly when many of those rejected artists are quintessentially New Orleans in someone's mind.

But is it solely a social media phenomenon? Another web-based echo chamber with a mad on for Jon Bon Jovi? Or has something meaningful changed? Jazz Fest remains overwhelmingly oriented toward New Orleans and Louisiana music, and complaints that it’s “not New Orleans enough” make you wonder what percentage would be enough.

To better understand this phenomenon, we looked at past and present Jazz Fest lineups to see what the evidence says. Are locals actually losing ground to national acts? Is there any reality to support these fears and concerns? Or is another occasion where anxiety fuels suspicion which fuels sky-is-falling, doomsday proclamations? We don’t have the manpower for a comprehensive overview, but we looked at three four-year periods: the last four years (including 2015), 2001 to 2004, and 1992 to 1995 for a snapshot study to put some information into a conversation that is often dominated by emotion, memory, and anecdotal evidence.

We selected 2001 to 2004 because those were the years that led up to AEG Live coming on board as partners with producers Festival Productions to produce Jazz Fest. In 2014, Quint Davis told Keith Spera at Nola.com:

They said, “You can't cut your way out of this. In order to grow the festival, you have to spend more money, not less.”

That was the actual tipping point of how things changed with AEG. That was the sea change.

According to Spera’s article, Jazz Fest lost money in 2004, and Davis was faced with the question of how to deal with that. Festival Productions formed a partnership in 2004 with AEG Live, which also produces Coachella, and that gave Festival Productions the resources necessary to treat the Acura, Gentilly, and Congo Square stages as main stages and spend accordingly on talent. Some acts now cost more than a million dollars—a clear change from the past.

The earlier sample period was chosen with help from friends on Facebook. I asked, “ If you think Jazz Fest went off the rails, when did it happen? What band, bands, or event was the tipping point for you?” and many participants in the conversation pointed to AEG Live coming on board, while others focused on the high profile sponsorships.

“2000 was the first year that cars (Acura) came on to the fairgrounds and music went into the parking lot. It used to be the other way around,” singer Debbie Davis says. Her ironic symmetry is on point but at odds with the time line. Acura did come on board in 2000, but music first moved to the parking lot in 1994 after the grandstand burned down on December 17, 1993. The Jazz and Gospel tents moved to the parking lot in 1998.

Poet Ralph Adamo had a truly old school suggestion—when the festival banned kite flying—and media producer Kim Lloyd wrote, “The change came when we no longer needed the flagpole,” a thought that is more about the march of time and technology than anything Festival Productions has or hasn’t done. Music journalist John Swenson has similarly talked in the past about the impact of time on the talent pool that once defined Jazz Fest. These days, the festival soldiers on without Professor Longhair, James Booker, Eddie Bo, Danny Barker, Snooks Eaglin, Earl King, Ernie K-Doe, and now Bo Dollis, just to name a few. The cumulative effect of these deaths is that New Orleans’ musical history and the sensibility that shaped it for so long is felt more lightly on the Fair Grounds than it once was.

But many identified years when specific bands played. Sting in 2000 and the Dave Matthews Band/Mystikal train wreck in 2001 were popular choices because they seemed to mark occasions when music in the commercial marketplace became part of the generally roots-oriented Jazz Fest. Before them, visiting artists such as Al Green and Ray Charles certainly had hits, but when they first performed at the festival—Green 1983 and Charles 1995—their days as chart-toppers were largely behind them (though to be fair, Green would return to the top ten with his cover of “Put a Little Love in Your Heart” with Annie Lennox from the Scrooged soundtrack in 1988). Before Sting, no individual act commanded a six-figure payday to play.

The economic changes that accompanied Acura and Shell were unquestionably massive game changers. Jan Clifford and Leslie Blackshear Smith’s The Incomplete, Year-by-Year, Selectively Quirky, Prime Facts Edition of the History of The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival put the value of Acura’s sponsorship in 2000—along with Riffage.com dollars to pay for webcast rights—in the neighborhood of $1.5 million. Shell came on board in 2005 as the title sponsor, and those cash infusions along with AEG Live’s bankroll clearly affected the possibilities of what Festival Productions could do.

But the money by itself doesn’t affect people’s attitudes toward the festival as much as what Festival Productions does with it. Acura on-site showrooms and Shell hospitality tents pass barely merit a grumble on a good day at Jazz Fest. Nobody complained about money spent on Bruce Springsteen and the Seeger Sessions Band in 2005, or Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in 2012. Bon Jovi, on the other hand, has become the poster band for everything wrong with a more star-oriented Jazz Fest, and it doesn’t help that they have played it twice. I settled on the years leading up to 1996 when Phish first appeared at Jazz Fest. It was the earliest point when a national band was a source of controversy that anybody in the conversation remembered.

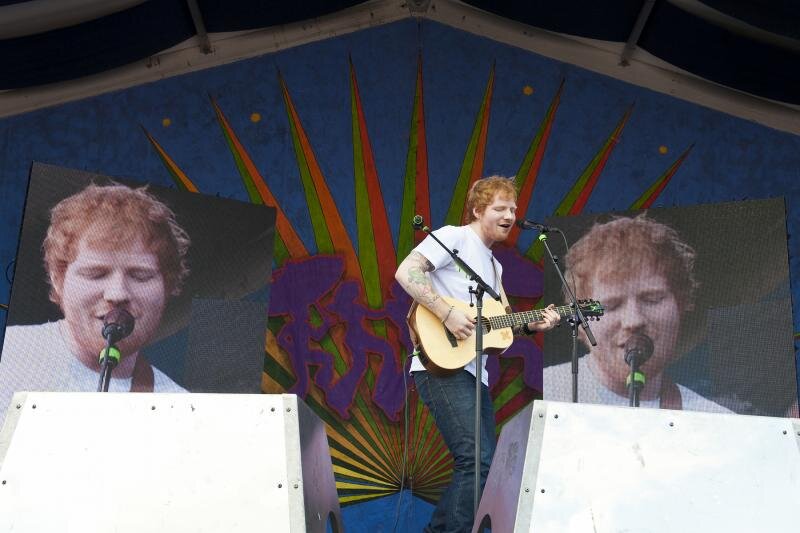

For each of these time periods, we recorded whether an act was local, from Louisiana, or from outside Louisiana, and we looked at when they played and for how long. One of the complaints is that Jazz Fest may still be New Orleans-heavy, but the emphasis is on the national acts. When this year’s talent lineup was relesed, no Louisiana act appeared until the third line, where Trombone Shorty and Orleans Avenue and Jerry Lee Lewis shared a line with Hozier and Widespread Panic. Above them were Elton John, The Who, Jimmy Buffett and the Coral Reefer Band, Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga, No Doubt, Keith Urban, John Legend, Ed Sheeran, T.I., and Chicago. The fourth line was Ryan Adams, Steve Winwood and Wilco, the fifth was The Meters. We wondered if that seeming priority structure carried over to the Fair Grounds.

One challenge we faced was the age-old question of deciding who is local. In general, we felt like you had to live in New Orleans to be considered a New Orleans act—a position that seems obvious, but what do you do with The Dixie Cups, some of whom live in Florida? Or Charles Neville, who hasn’t lived in New Orleans for years? Does Henry Butler get a pass, even though he left New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and if we did consider him a New Orleans act, how would the fact that he is playing with New Yorker Steven Bernstein affect things? Going with people who play “New Orleans music” seemed equally problematic, as did including New Orleans-friendly artists such as Texan Marcia Ball. How friendly do you have to be to be considered one of our artists? In the end, we considered them all to be from outside Louisiana.

A more finicky question we faced was a geographical one: How far from New Orleans can you live and still be a New Orleans artist? Are musicians from Slidell or Kenner or Harvey acts from New Orleans? Because deciding on a distance or dividing line seemed arbitrary, we decided to classify those acts as from Louisiana. That means our head count for New Orleans acts might be more restrictive than yours, but the New Orleans artists combined with the Louisiana artists will give us a pretty good picture of how firmly fixed to its region Jazz Fest is.

Tomorrow: Let’s Look at the Numbers