How New Orleans is Jazz Fest? Part 5

An update of our 2015 series looking at what Jazz Fest's scheduling suggests about the festival's relationship to New Orleans.

Kvetching about Jazz Fest is a spring tradition as beloved as cobbling together a Mardi Gras costume on Lundi Gras night. When the rejection letters go out, artists share the bad news on Facebook that the festival will go on without them, which prompts friends and fans to clutch their ePearls and shake their eFists at the Acura-zation of Jazz Fest.

Last year, we looked at three four-year blocks of the festival’s lineups from the mid-’90s to 2015 to gauge how Jazz Fest’s demonstrated commitment to New Orleans had evolved. I absolutely believe that in the hearts and minds of all the organizers, New Orleans is the unquestioned soul and star of the festival, but what story do the cubes tell? Do they suggest, as some fans of New Orleans' musicians charge, that Jazz Fest has forsaken the city that inspired it in favor the parade of gold and platinum-selling artists that populate the top lines of its annual talent announcement?

The answer we found was no and yes. Musicians from New Orleans and Louisiana and the roots-based music they’re associated with remain the backbone of the festival in raw numbers and percentages—between 75 and 80 percent in the last four years, just as it was in the mid-‘90s--the earliest period we looked at. At the same time, the festival schedule mirrors the marketplace more than ever as the bigger names command more time and more prominent slots. That change is a natural byproduct of Jazz Fest’s AEG Era (2005 to present) and its effort to “spend more money not less” to grow the festival, as producer Quint Davis said in 2014. You don’t pay Springsteen money to get 50 minutes out of him in the 4 o’clock hour as a lead-in to Rebirth.

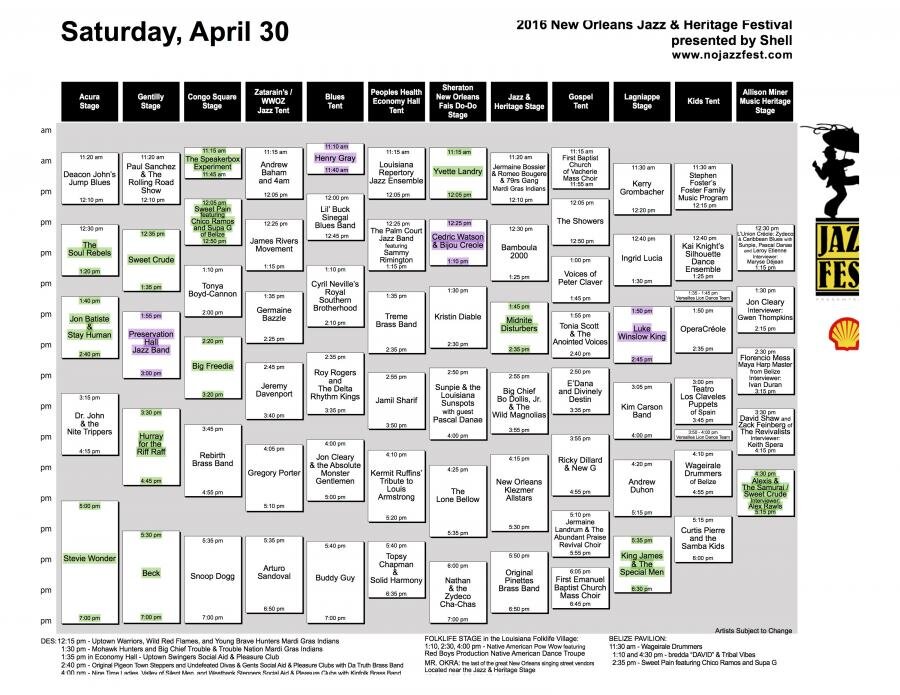

Last year we examined the whys and wherefores of that change and wondered how many headliners New Orleans actually has these days. As the city’s funkiest generation moves closer to that Last Jam, the city’s left with fewer artists who can reliably draw headliner-sized crowds. This year, Trombone Shorty and Christian Scott are the only two New Orleanians this year to close the Acura Stage, Gentilly Stage, Congo Square Stage, Blues Tent, or Zatarain’s/WWOZ Jazz Tent. Last year, we could count the number on one hand (plus two fingers): Shorty, Delfeayo Marsalis and the Uptown Jazz Orchestra, Voice of the Wetlands All-Stars, The Terence Blanchard E-Collective, Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Buddy Guy, and Dr. John’s tribute to Louis Armstrong. Of those, only Shorty and Dr. John were on the Acura and Gentilly stages.

It’s tempting to read that as an indictment of the festival or the current crop of New Orleans musicians, but a look at the small club of bands that top lineups around the country during the summer festival season shows that no city is growing headliners like it once did. The splintering of the monoculture means that people whose tastes were once shaped by the same television networks, radio stations, local papers and newsweeklies now self-sort themselves into communities built around a thousand points of cable television, satellite and Intenet radio, streaming services, and websites. Each has its own musical favorites that scratch a niche, which means Taylor Swift-like successes don’t happen like they once did.

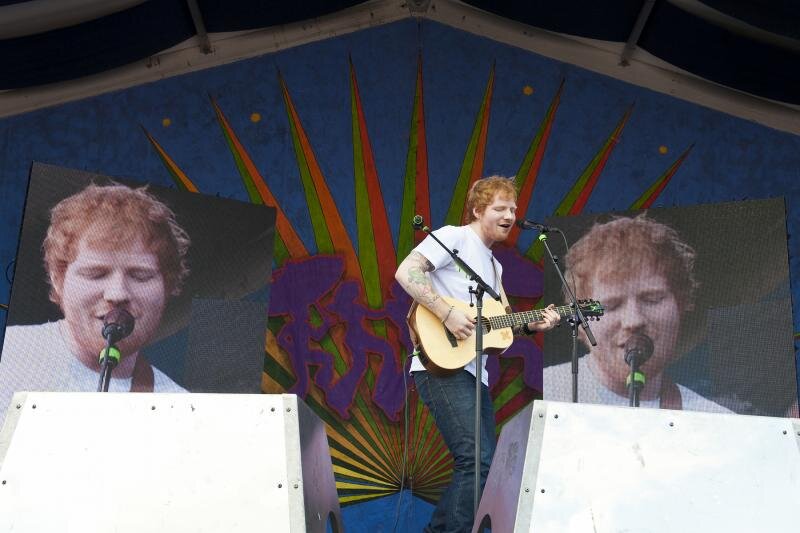

Headliners may be as scarce as moderate Republicans, but it’s hard to accept that there are fewer artists who can play the penultimate slots. For years, Quint Davis has spoken proudly at Jazz Fest’s cubes announcement press conference of the way New Orleans Artist A would play next to Out-Of-Towner B, and New Orleanian C would perform in front of International Star D. Each pairing, he implied, was a little curated gem of a concert set in the tiara that is Jazz Fest. You saw that sort of programming logic at play at Jazz Fest on Sunday when all of the acts on Gentilly skewed toward younger audiences because former Jonas Brother Nick Jonas headlines. That gave Royal Teeth the most responsive Jazz Fest audience it has enjoyed yet, but they didn't play before Jonas. That honor went to Los Angeleno Elle King. Out of town bands closed the stage that day, and that happens more this year than ever.

The phenomenon isn’t new this year. There hasn’t been a year in the 2000s when it didn’t happen at least once, but in 2014, the number grew to seven, and in 2015, 12. This year, it happens 18 times. Michael McDonald opened for Steely Dan on the opening day, which made Buckwheat Zydeco the last Louisiana artist on the Acura Stage, and he finished at 3:05. In the Blues Tent, the subdudes finished at 3:50 before Walter Trout and Sharon Jones and the Dap-Kings performed. Cowboy Mouth exited the Gentilly Stage at 2:40, when the band turned the stage over to Grace Potter then Gov’t Mule. Cowboy Mouth, Flow Tribe and Johnny Sketch and the Dirty Notes played for a combined 145 minutes that day, whereas Potter and Gov’t Mule played for a combined 170.

This year, two visiting acts close out those five stages 51 percent of the time, and while there are days when it only happens once, there’s no day when it doesn’t happen at all. On Sunday, the last three acts on Congo Square were from out of town. Rapper J. Cole closed, and he was preceded by Carlos Vives and Dédê Saint-Prix Band of Martinique. Actually, it could be the last four were from out of town because Henry Butler preceded them, and Butler’s not originally from New Orleans, nor has he lived here since he left after Hurricane Katrina. He certainly puts New Orleans’ music on the stage, but for the purposes of math, no current New Orleans or Louisiana resident plays that stage after ManzaNota/Rock en Espanol ended its 55 minute set at 12:15.

Cherry picking the stages to discuss does skew the numbers, but since those five stages present the most out-of-town bands, the decision seems fair. Still, putting the numbers in the context of the entire festival only makes them less dramatic--21 percent this year instead of 51 percent. The story remains that the number of stages with two out-of-town bands is trending up, from 14 percent festival-wide in 2015.

To the average festgoer, a good show is reason enough for any choice, and perhaps the philosophical consistency horse is so long out of the Jazz Fest barn that trying to find any is akin to leaving snacks for Santa. But since the festival’s connection to New Orleans is a central part of the story that it tells each year, how that connection manifests itself merits some scrutiny. For me, the growth in the number of back-to-back sets by national acts is more disconcerting than the national headliners because if you’re a local Stevie Wonder fan or Beck fan, there's a good chance that you're buying your ticket that day to see Stevie or Beck. The rest of the festival is lagniappe. For you, the festival that day is a Stevie Wonder or Beck concert with 11 stages of opening acts, and you want to see a whole set. Stevie and Beck may have played the hometown of a tourist from Wisconsin months ago, but if you’re local, the Jazz Fest show is your one and only chance to see the band on this tour. And—in their cases specifically, tickets to their Jazz Fest shows will be cheaper than they were for their most recent concerts in New Orleans, when both had tickets on sale for more than $100.

But if I were a Michael McDonald fan, would I have been satisfied by a 75-minute show? If I were a Grace Potter fan, would I really think she’d been done wrong if she and Cowboy Mouth swapped slots? Walter Trout and the subdudes both played hour-long sets in the Blues Tent; would it have been so hard to flip them?

Such changes would do little beyond improve the optics, but what we currently see is that New Orleans and Louisiana acts serve as opening acts to national acts in greater number and frequency. Local artists are presented as the pretext rather than the reason for the festival, and while I don’t for a minute think that’s what’s going on in the minds of Festival Productions, it’s a message the festival’s lineup sends.

Last year, we scrutinized the lineup and its contexts in greater detail and with greater nuance to better understand the forces that shape Jazz Fest today and fuel the discontent many feel toward it. You can find the story here: