NOMA Hosts Arthur Roger's Contemporary Art Mixtape

The Julia Street gallery owner donated his art collection to NOMA, and the show says as much about Roger as the art he has collected.

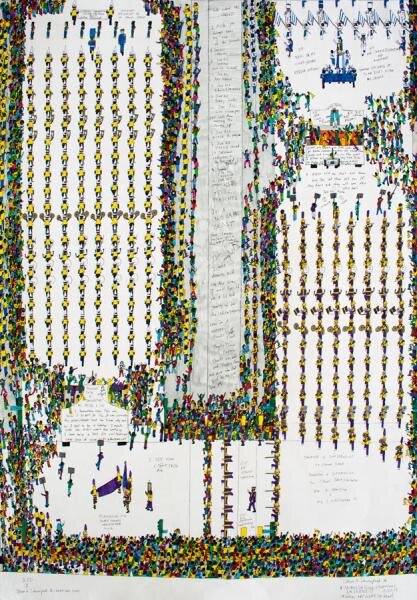

First note on “Pride of Place: The Making of Contemporary Art in New Orleans”: Some collectors’ collections I’ve seen in museums were startling in the number of inessential pieces by essential artists, but the exhibition of pieces donated to the New Orleans Museum of Art by gallery owner Arthur Roger represents the included artists well. If the only Willie Birch piece you see is his “An American Family,” you've got a goodidea of Birch is about. You know the Robert Gordy is representative because NOMA’s Great Hall features other works by him, and Ida Kohlmeyer’s “Synthesis BB” presents the shapes, colors and patterns that she would juggle and juxtapose until her death in 1997.

Second note on “Pride of Place,” which will remain on display until September 3: It’s best thought of as a mixtape. The one voice that runs through the show is Roger’s, and you can see how 90-plus percent of the works in the show could live in the same collection. There are features—George Dureau’s photos make a few appearances, as do pieces by John Waters—and the whole is livelier than its concept. Some pieces feel like New Orleans’ greatest art hits—Gene Koss and Lin Emery sculptures, for instance—but there’s also a small, surprisingly provocative neon Star of David sign by Keith Sonnier hung on the wall. The Gordy headshot is unusual in its roundness, and my daughter thought it looked like the black and white photo of Andy Warhol by Greg Gormannext to it minus Andy's ‘80s spiky-haired wig. On one wall, Simon Gunning’s “The Red Barge and the Yellow House” gives us Hurricane Katrina’s destruction as devastation. On another, Michael Wilmon’s “The Great Katrina Flood, 2006-7” presents post-K New Orleans as dark comedy enacted by Dia de los Muertos skeletons, and it’s not clear which is more powerful.

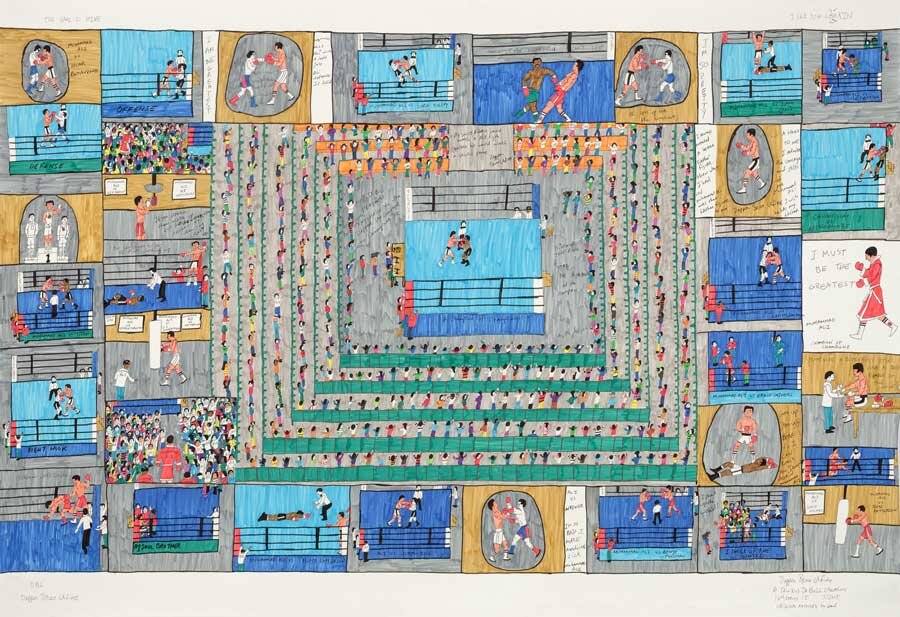

Some pieces reflect tastes that surprise. Roger’s affection for John Waters’ work, for example, seems generous to be charitable; a blind spot to be less so. Waters’ multimedia pieces are wickedly funny, but once you get the joke, they’re done. One collects screen shots of famous moments from movies with the key line added as a subtitle in Pig Latin. Under the wintry mouth of Orson Welles in Citizen Kane, a caption reads, “Osebud-Ray.” Funny, but the piece isn’t so visually dynamic that you have a reason to return to it and see if there isn’t more to unpack. On the other hand, “Untitled (Ark)” by Radcliffe Bailey is deceptively rich with possibilities as a simple sailing ship is rendered black with sparkles, which makes associations with the slave trade inescapable, along with what slave ships represented and to whom. The sculpture’s simplicity also brings to mind Culture’s “Black Starliner Must Come” and the Afrofuturist visions of ships—sailing, space, and otherwise—that will facilitate African Americans’ escape from bondage culture.

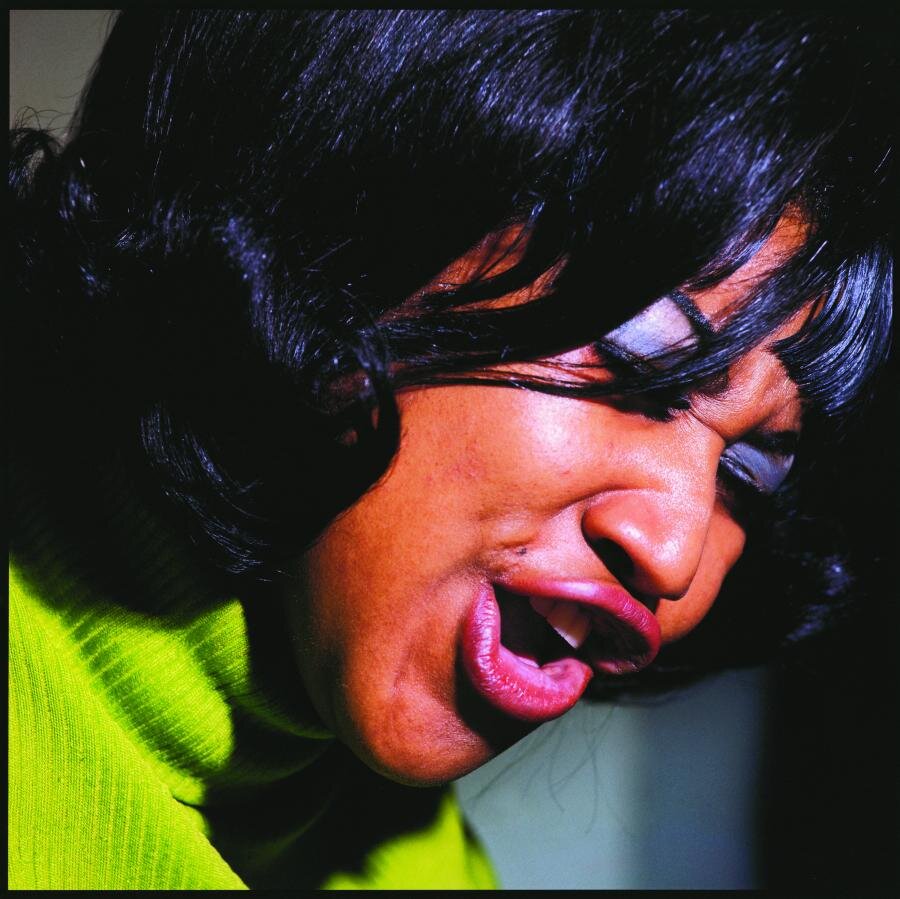

Third note on “Pride of Place”: The show is unified by an inclusiveness that reads as natural. The artists and the figures depicted in the show cross ethnic, gender and sexual spectrums, but no selection seems obligatory, nor does anything appear to be included solely for its message. Many have clear political points of view including “The Vanity Table” by James Drake, which presents a number of erect guns on a table, but the composition stands on its own as well. Similarly, the show’s subtitle may be “The Making of Contemporary Art in New Orleans,” but the selections aren’t dogmatically local. In addition to John Waters, “Pride of Place” includes a Robert Mapplethorpe photo and a riff on Andy Warhol by San Antonio’s Deborah Kass that is itself an unassuming but dense way to start the show as the photo’s play with identity, feminism, and art history is rich and satisfying fun to think through.

That unforced quality is consistent with my experiences with Arthur Roger (including this interview), but my wife came away with the same vibe without having met him. As a result, “Pride of Place” makes a strong argument for the quality of art to come out of New Orleans (for the most part) in the past 40 years and for Roger as one of the figures who helped it find an audience.