Lee Friedlander Shows His Double Vision in NOMA Show

The photographer's show of images from the 1950s to the 1970s shows changes in his own work and in New Orleans itself.

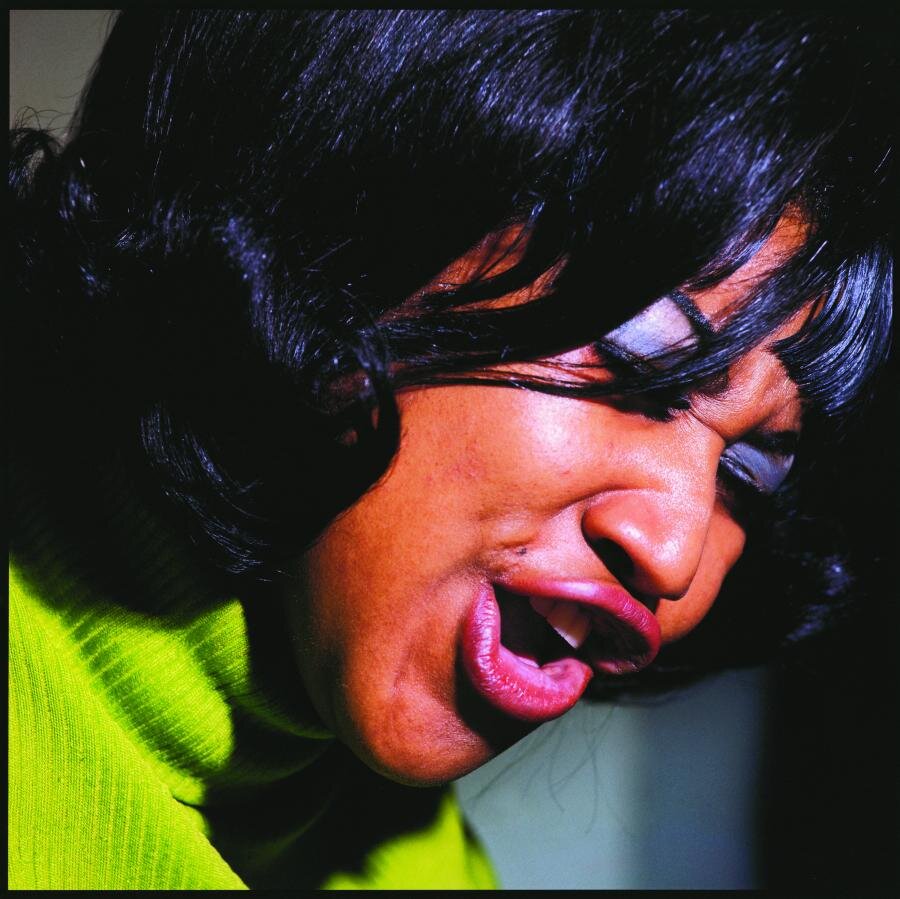

Portraits of musicians often feel as ephemeral as pop songs, not because they lack emotional gravity but because so many convey the same thing—intensity. The photos by Lee Friedlander of Miles Davis, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Aretha Franklin and more in the great hall of the New Orleans Museum of Art are studies in intensity, whether its in Davis’ confrontational eyes, Johnny Cash’s steely stillness, or Kirk’s face almost exploding as he plays two horns at once. Still, the photos are engaging in part because of their large scale, and because of the simple richness of their colors. The skin tones particularly are warm and gorgeous, inviting the viewer into the artist’s world.

What makes this show of Friedlander’s work so interesting is that all of those characteristics were by professional design. He shot them and many more as the house photographer for Atlantic Records, and the photos were taken to be used on covers and as publicity art. That knowledge invites you to think about what—if anything—separates these portraits from those shot in less mercantile circumstances, and about the role photos like these play in the selling of a musician. What does it say about what we want from our musicians that the photos tell a similar story?

That show went up during Jazz Fest and will remain on display until June 17. It serves as an introduction to the larger show elsewhere in NOMA, “Lee Friedlander in New Orleans.” Friedlander is one of the most famous living photographers, and he first visited and photographed New Orleans in 1957. The show starts with photos from his early visits, and time hasn’t been kind to them. Photos of African-American musicians and the street life that informed the music were progressive when Friedlander and many others shot them, but we’re now too familiar with the dispassionate, journalistic, class- and race-conscious voice of the photos that owed a lot to Robert Frank and Walker Evans. And, it’s a voice than many have adopted since, so much so that they seem familiar, even when you’re seeing them for the first time. The photos are excellent, but they require a historically conscious viewer to fully appreciate them today.

The photos that make New Orleans the subject hold up better because they come at a time when the ways New Orleans is changing is a source of anxiety. It’s tempting to see photos from the city in the ’60s and ‘70s through a WYES/Ain’t Dere No More lens, but those weren’t friendly times for the people Friedlander photographed in the exhibition’s first room, so any nostalgic impulses should come with at least an asterisk.

The familiarity of the locales makes it easier to appreciate Friedlander’s art, though. Many of the photos illustrate his ability to integrate reflections into his photos, sometimes nakedly as he shot what he saw out of the window of a car, including the side mirror and the reflected Orpheum sign seen in it. In street scenes on Canal Street, he played with reflections more subtly, making the effort less obvious and the disjunction between the reality in front of him and the one depicted in the photo less obvious. In one domestic photo, he shot a sideboard with a mirror, simultaneously capturing the back of a man who is talking as well as the framed photos of family members positioned on the sideboard. The effect quickly, effortlessly suggests that these women—primarily—are always on his mind, no matter what he’s doing, and it gives the photo drama even though we never see his face.

One series of photos comes doubly laced with irony. Friedlander regularly photographed the Plaza Tower, juxtaposing its elegant, modern look in the 1960s with street level, urban wreckage—bent, battered, barbed wire fences and wobbly stacks of spare tires by the freeway. In the moment, the photos suggested a tension between the city’s aspirations and its street-level reality, but since the building has stood empty since 2002 in need of asbestos remediation, those images now suggest that even the dreams had issues.

That kind of pointed juxtaposition shows up throughout the show. One photograph depicts the monument to Robert E. Lee in Lee Circle shot during Carnival, with the criss-crossed metal scaffolding of the viewing stands seemingly boxing in and imprisoning Lee. Friedlander similarly shot the Spanish-American War monument casting a long shadow across the street toward him as the skeleton of the Superdome in the process of being built rose behind it. The latter is not as controversial, but in much the same way that Friedlander uses mirrors to shoot what’s in front of him and behind him at the same time, those images look at the past and the future simultaneously.

“Lee Friedlander in New Orleans” will be on display through August 12, and the 20 or so years covered give the show room to document his growth as an artist. I can imagine the Atlantic portraits and documentary photos being many people’s favorites, but the show is more compelling and distinctive when Friedlander’s subject ultimately becomes photography itself and the ways to manipulate reality inside the camera. The works never become cold or formal exercises, though. In “Lee Friedlander in New Orleans,” we see an artist working out his ideas about photography in a city that offered a rich set of images and metaphors with with to play.

Friedlander curated a Spotify playlist to accompany the “American Musicians” show.