The Dapper Bruce Lafitte Takes on Basquiat, Picasso and Himself

In a video interview, the artist whose Muhammad Ali-themed show is on display now in the Arthur Roger Gallery talks about the art world, Ali, and his name.

Bruce Davenport Jr. first got attention doing diagram-like artworks that illustrated New Orleans high school marching bands in the streets of New Orleans. His pieces were featured in the great hall at NOMA for Prospect.2, and they walk a naïve/contemporary art line with a personal notion of perspective and big, geometric designs rendered in marker and ink. They also include graffiti-like shout-outs written in white spaces on his pages to friends and family in his works, suggesting that the pieces are more than just representations of an interest but platforms for him to say what’s on his mind.

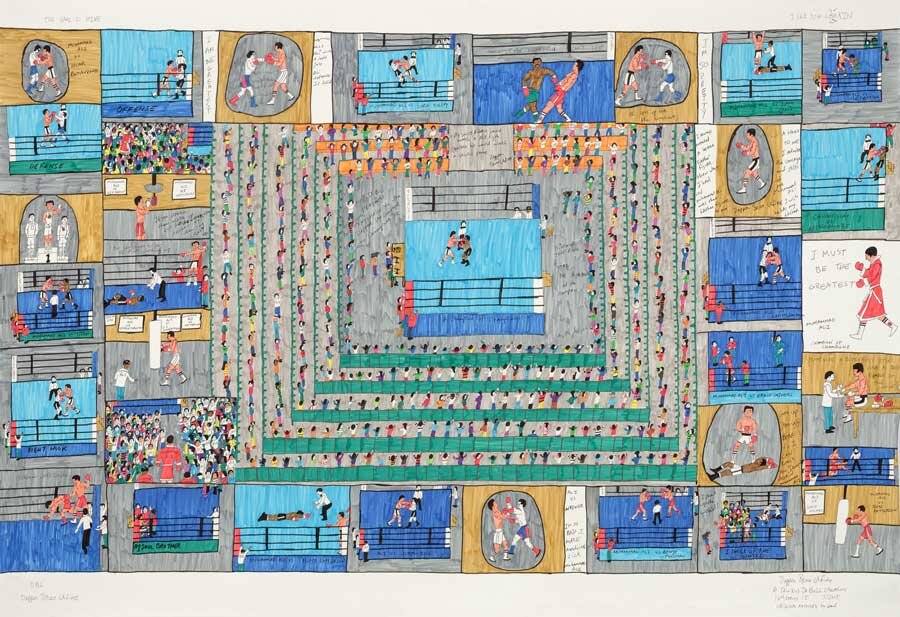

Currently, his art in on display in two venues in New Orleans. He has marching band pieces in the Stella Jones Gallery’s “10 Years Later—A Black Perspective” and his “The Dapper Bruce Lafitte Introduces: Draw Like a Butterfly, Sting Like a Bee” at the Arthur Roger Gallery. The four large works in the latter show continue in his geometric style, though this time he uses it to illustrate the career of the boxer Muhammad Ali. The pieces are often quilt- or comics-like in the way his page is broken up into a series of boxes, but panels are not organized in a narrative sequence. The show is his second boxer-themed project—he did one on Mike Tyson that opened in February at the Louis B. James Gallery in New York, and he plans to do one on Joe Louis. The idea behind the series, he says, is that Tyson is his favorite boxer, Ali was his father’s, and Louis was his grandfather’s.

Seeing the Tyson show next to his current show helps make Davenport’s control of his art clearer. The Tyson show is less ambitious with some pages simply depicting boxing arenas the night of the match, while others are broken into loosely defined nine-panel grids with the corner boxes rendered lightly in black pen on white backgrounds. That creates a clear visual hierarchy not present in the Ali works. They have little quiet space with panels bordering a central image of a boxing arena, and almost nothing is left untouched or even casually touched. They’re aggressively colorful, and because of that the eye isn't distracted as much as it's pushed and pulled around the page. The works are also--appropriate for the boxing theme--pugnacious. In text written on the pages, he calls out Jean-Michel Basquiat and Picasso, both of whom inspired him but more for their business acumen and legacy than their art.

The show hangs in the same room as a series of photos of Muhammad Ali by the late photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks, and the two work well together. Davenport’s show is a first-person meditation on the public Ali and his mythic stature, while Parks’ photos are impersonal documents of his physical reality. One photo of Ali sparring shows a punch to be a full-body action that even involves his facial muscles, while the photos of Ali relaxing in loungewear and praying over a meal have a clear physicality and grace. Parks’ photos explain why Davenport’s works exist.

Lauren Keenan and I recently talked with Davenport about his work, Ali, competition, and his name.