New Reissues Make the Case for French Pop Star France Gall

The recent Third Man vinyl releases present her music from the late 1960s at its most delirious and complicated.

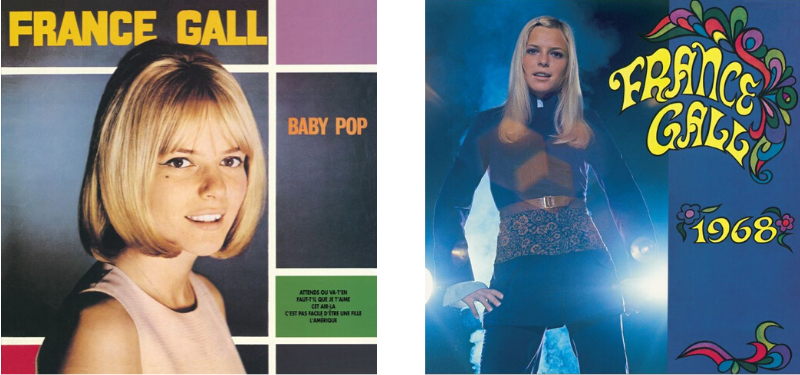

For those who haven’t followed French pop through the decades, the France Gall story centers on two events—winning the Eurovision competition in 1965 at the age of 17, and feeling humiliated by French singer and songwriter Serge Gainsbourg. He wrote a number of songs for her including the Eurovision-winning “Poupée de cire, poupée de son,” and one song, “Les Sucettes,” which liberally used double entendres to make a song about lollipops sound like an ode to oral sex—something she didn’t realize when she recorded it. It’s easy to imagine the song being a cause célèbre because Gall’s musical persona was so youthful that her second album was titled Baby Pop, and it prescribed her brand of youthful pop--called “yé-yé,” like The Beatles “yeah yeah”— as an antidote to the workaday grind.

That story is and isn’t present in the Third Man Records’ release of Gall’s first three albums on vinyl in the U.S. for the first time—Poupée De Cire, Poupée De Son, Baby Pop, and 1968. We do hear what made her a European sensation, but the callous sexualizing of Gall is not obvious in the tracks. “Les Sucettes” isn’t on the albums, and only her slightly breathy vocals give the songs a sexual dimension. Musically, the songs live in the space where orchestrated pop and rock ’n’ roll overlap—a space that now sounds charmingly corny with woodwinds, strings, mariachi brass, and twanging electric guitars. The Austin Powers movies mocked the discotheque world that songs like Gall’s fueled, but freed from Mike Myers’ cinematic universe, these songs have a lot of life in them. Anything goes in them, so there are moments that evoke Sergio Leone’s spaghetti western soundtracks, while others evoke the breathless hustle of downtown jazz. They’re often delirious with a Farfisa organ merrily bouncing around the melody, and “Baby Pop” turns into a march during the chorus, announced by pounding on a bass drum and answered by a cascade of yé yé yé from backing vocalists that place Gall in the world of girl groups.

But as the focus on the sound suggests, these are producers’ albums. Gall is the voice and the face of these albums, but her unhappy memory of those times hint at how little agency she felt. “She's cute, isn't she? A-do-ra-ble!,” Gall told an interviewer in 2018 while looking at the booklet that accompanied the release of a box set of her music from the 1960s. “I naturally tend to consider this girl as someone else because I know she was not happy and I do not want to integrate her into my life. She was me but doesn't look like me. You have to understand one thing: I am gifted for what I do, for singing, for this profession which is to sing. However, I did not want to be exposed at all, I was not happy to find myself under the gaze of others, it was something very violent, very aggressive.” (Note: That is a Google mechanical translation from French, but you get the idea.) Producer Denis Bourgeois paired Gall with bandleaders and arrangers Alain Goraguer and David Whitaker, and while their work is sympathetic, there’s no sense that the arrangements were tailored to Gall’s talents.

Like so many young, female pop singers before and after Gall, the focus was on her youth. It made her appearance in the Eurovision competition notable, since prior to Gall the European singing competition tended to feature clearly adult vocalists singing overworked, florid ballads. Her signature song, “Poupée de cire, poupée de son,” foregrounded her age as well since “poupée” is French for doll. The title “Baby Pop” and the cover photo of Gall with a blonde bob and cat’s eye makeup emphasized her youth. The cover of 1968 presents Gall with her hands on her hips in a power stance while wearing a blue tunic pant suit, as if to say I’m all grown up in a still-girlish voice. Her image, sexism, the generally dismissive attitude toward pop music and pop singers in the music industry, and Gall’s memories make it easy to imagine a musical circumstance that worked around Gall more than with her. You can similarly imagine that a misanthrope like Gainsbourg found the prospect of getting someone so blonde and angelic to sing the praises of blow jobs to be irresistible, so much so that the bigger surprise is that there aren’t more. And there might be. The French wordplay doesn’t survive translation to English, but many hear “Poupée de cire, poupée de son” as Gainsbourg claiming Gall as his singing doll, someone who’d have nothing to say if not for him.

Still, these albums make a case for Gall’s significance anyway. So much of the writing about her in this period focuses on Serge Gainsbourg’s contributions, but it’s not obvious which songs are his, or that there are a number of writers on the albums. She unifies the songs with her performances and persona. Nothing on the albums says that the focus on her is unearned or unworthy. By 1968, the psychedelic elements in the song are strengthened and it’s a little less eclectic. The album sounds like an effort to help transition her into a mature artist, though “mature” is very relative in this circumstance. It includes the amazing, bizarre “Teenie Weenie Boppie,” an unfortunately titled song about a bad LSD trip that’s too bouncy to match the death trip story it tells.

I wonder if I’d enjoy these albums as much if they were recorded by an American artist today. Would I find Gall self-infantilizing or merely youthful? Would I detect more clearly the manipulations of the men around her if 50 years and the French language didn’t stand between me and a more complete appreciation of these records? As is, they live in a similar place as The Rat Pack for me—completely engaging artifacts from a very different time that are now as hard to fetishize as they are to deny.