The New "I'm So Free" is Quintessential Lou Reed

The briefly available collection of 1971 demos doesn’t tell us much new about Reed, but it brings the tensions that animated his career-defining period into clearer focus.

When we last saw Lou Reed in Todd Haynes’ documentary The Velvet Underground, we got him as a product of New York’s avant-garde art scene. The modern art community is an important backdrop for not only Reed and the Velvets but punk rock, in part because members of Andy Warhol’s extended cinematic universe turned up in their audiences and sometimes on their stages, adding elements of drag, camp, fashion, film and theater to the mix. Those touches contributed to scene’s love-in-the-gutter romanticism that made some bands more appealing than the music they played.

By roping avant-garde cinema into the Velvets’ story, Haynes expands the circle of art references beyond the obligatory pop art. But even that is too narrow a frame. One of the other important gigs for musicians at that time was Max’s Kansas City, which was an artist-friendly bar where Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, Willem De Kooning and others would trade art for bar tabs. In that space, pop art was just one movement among many up for discussion. "People talked about art" at Max’s, according to composer Philip Glass, "They threw each other through windows because they disagreed about art.”

New York City punk can heard as an extension of those Max’s Kansas City conversations as questions about what rock ’n’ roll was and how it manifested itself can be heard in those records. That is certainly the case with The Velvet Underground and Reed. The formal audacity of The Velvet Underground and Nico and White Light/White Heat invited listeners to figure out the subtler frames that bracket The Velvet Underground and Loaded, or if those albums somehow represented a “true” Velvet Underground, the one that was simply a rock band.

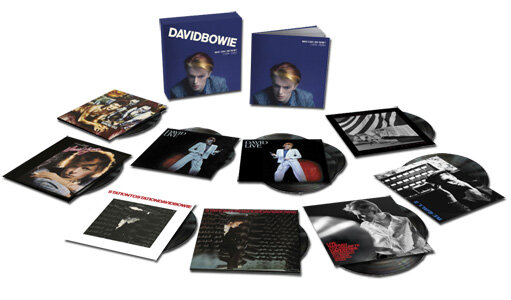

Just when you decide that maybe Reed had settled into being being a conventional rock band—by his standards, anyway—on those albums and 1972’s Lou Reed, he adopted his own Warhol superstar glam persona for Transformer. With the help of David Bowie’s production, Reed destabilized any assumptions about the contexts for his albums. The run of albums that followed it—Berlin, Sally Can’t Dance, Metal Machine Music, Rock ’n’ Roll Animal, and Coney Island Baby—are as bold as the first two Velvets albums in the complicated ways that they present the relationship between the artist, his art, and his audience. It’s no surprise that Bowie found his way to Reed since both asked who and what are we listening to when we hear a song.

I’m So Free: The 1971 RCA Demos doesn’t answer those questions because the best art can’t be reduced to a sentence or paragraph. Not that it matters since the album requires work to find. During the week of Christmas 2021, RCA/Sony released the album through iTunes in Europe as a way to extend the label’s ownership over the material. Once that had been achieved, it took I’m So Free off the market again. Now RCA/Sony can once again squirrel the 17 songs away again until the day comes when it decides to do something with them.

That’s too bad because this release was a perfectly good use for them. The demo nature of the tracks—Reed singing and playing acoustic guitar—makes it tempting to hear them as Lou unfiltered. He certainly delivers the songs with decisiveness, but it’s not clear if he’s giving us a window into his soul with songs that speak for him, or if he simply believes in this batch of songs so strongly that he gives them the performance they deserve.

It’s easy to lean toward the former since we instinctively attribute an honesty to the acoustic demo, as if electric guitars and the introduction of a band somehow add layers of artifice to songs. MTV built its “Unplugged” franchise on that premise, but it has always seemed like a risky assumption to me. Reed’s performances show that he and not any underlying concept make Reed hard to pin down. Haynes’ documentary draws attention to Lou’s connection to the demimonde he wrote about, which invites listeners to hear his songs as autobiographical. But are they really? Or to what degree?

It’s similarly tempting to buy into the clarity of his unaffected vocals and think you’re hearing the real Reed, but you can’t trust his delivery. If listeners didn’t know it by Coney Island Baby, they learned that when he sang with great sincerity about wanting to play football for the coach—a phrase that nothing he’d written before gave listeners a reason to believe. I’m So Free reminds you that Reed’s pop sensibilities are so strong that he could get listeners to go with him into dodgy places.

“Perfect Day,” for instance, is a far thornier song than its chorus suggests. “It’s just a perfect day / I’m glad I spent it with you”, he sings, and the domestic intimacy of the lines and the lovely yearning in the melody invite you to take the song at face value. But in the midst of Reed’s recitation of a charmingly mundane get-together, he sings, “I thought I was someone else / someone good.” That note of self-loathing, when connected with the second half of the chorus—“You just keep me hanging on”—makes the relationship sound more complicated with notes of submission. The other person clearly controls the situation, and that’s more consistent with his lyrical milieu that a presentation of idyllic, romantic bliss.

That level of craftsmanship separates Reed from the inspirations that he surpassed and the imitators who never measured up. The songs on I’m So Free aren’t simply good blueprints in acoustic guitar and voice form; they’re satisfying as listening experiences because they have good bones. “Kill Your Sons” didn’t need the sturm und drang guitars to be engaging, which is saying something because it’s a very different and less successful lyric on I’m So Free. It’s one of the few places on the album where we hear Reed in process. The song showed up on Sally Can’t Dance as a bitter response to electroshock therapy—a part of Reed’s legend that his sister rejects in Haynes’ documentary—but here in an earlier incarnation, it’s an anti-war protest song. Reed presents the Vietnam War not as a battle between of the United States and Vietnam but wealthy adults and their children, who will one day “reclaim the land.”

[That’s not the recording on I’m So Free]

That protest song version of “Kill Your Sons” and Reed, stripped down to guitar and voice, point in the direction of Bob Dylan, who lurks in the background of Reed’s material. The 1995 Peel Slowly and See: 1965-1969 features pre-Cale demos of “I’m Waiting for the Man” and “All Tomorrow’s Parties” that are Dylanesque folk-rock, with Reed adopting a little of Dylan’s drawl in his vocal. On I’m So Free, that drawl spikes up periodically, signaling that even though Lou was the Dylan for a generation or two of his fans, Dylan himself was Reed’s Dylan.

The reference makes sense. Dylan played Greenwich Village during the early 1960s and the time that Reed was crystalizing the ideas that would become The Velvet Underground. Dylan visited Warhol’s Factory in December 1965 to film a screen test (audio is added to this version, I assume so it doesn’t get taken down), and the game-changing nature of Dylan’s early albums clearly affected the rock ’n’ roll world. Lennon and McCartney became more elliptical and allusive writers after hearing Dylan, and the 1968 Goddard film Sympathy for the Devil shows The Rolling Stones in the studio evolving the title song from a strummy, Dylanesque vibe to the form we know today.

It’s no surprise that a poetry-conscious Reed who had a similarly unconventional voice would take note of Dylan, and just as revealing as the mannered drawls on I’m So Free is how absent they are on the final versions that showed up on Reed’s albums. He may have felt Dylan’s influence when a thought began, but he was also aware enough of who he was as an artist to weed out and obscure those elements en route to completion. In 1993 when Reed covered Dylan’s “Foot of Pride” at Dylan’s 30th anniversary concert celebration at Madison Square Gardens, he intuitively translated Dylan into Reed so effectively that he made the song sound like one of his own.

Dylan’s output asked the same questions as Reed’s and Bowie’s. Just when you thought you knew who Dylan was and felt like you could identify the true Dylan in his music, he threw you a curve ball. Todd Haynes represented that fundamentally elusive nature by casting six actors including Cate Blanchett and Heath Ledger to play Dylanesque figures in his 2007 film, I’m Not There.

Unlike Dylan and Bowie, Reed didn’t take on obviously new personas, but nailing him down was never easy, which made him a natural in Warhol’s Factory where nothing was quite what it seemed to be. The “Superstars” weren’t superstars by any conventional definition, and part of Warhol’s art was to problematize the idea of the artist. Even The Velvet Underground’s popularity came with questions. Haynes’ documentary details the success of the band’s stint at the Dom, but like many NYC bands including the punks that followed, big in New York didn’t mean they were big. The Velvets’ trip to Los Angeles showed that many weren’t coming to gigs for the Velvets at all, and saw the band solely as an extension of the larger Warhol concept—a fair assumption at the time.

I’m So Free fits perfectly into that context because its status as an album is similarly provisional. It’s a collection of 17 songs that cohere together, packaged with cover art, and put on sale through a digital service provider. The sound difference between this release and the versions of these tracks that found their way to YouTube says at least some mixing and mastering done to prepare the material for release, but eight years after Reed’s death, it clearly doesn’t reflect any intention from him, and it’s no longer on the market. Even conversations about concepts feel dodgy because they imply a level of deliberation that Reed would dispute.

Maybe then, I’m So Free is the Reed we should get in 2021, as straightforward and complicated as Lou at any point in his career. It’s allusive and charming and frustrating because it feels revelatory while giving you reasons to doubt the revelations. It’s a useful addition to the Reed discography and perfectly Lou-like in its unavailability.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.