The Shangs' "Sonny Bono ..." is and isn't a Mystery

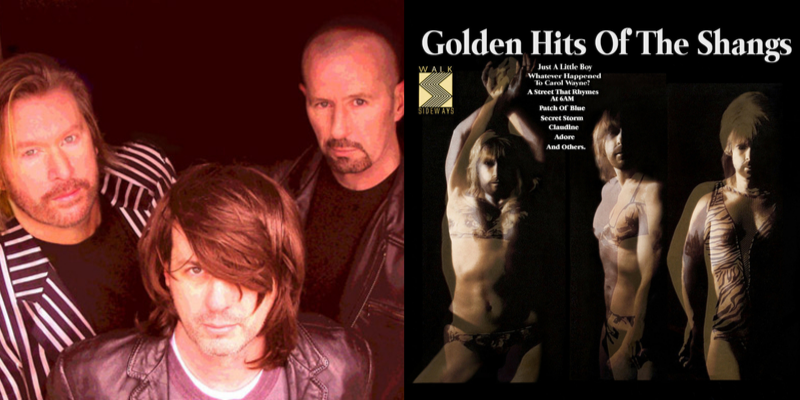

The album cover for the new album by The Shangs

The new album from the Canadian indie rock band asks more questions than it answers.

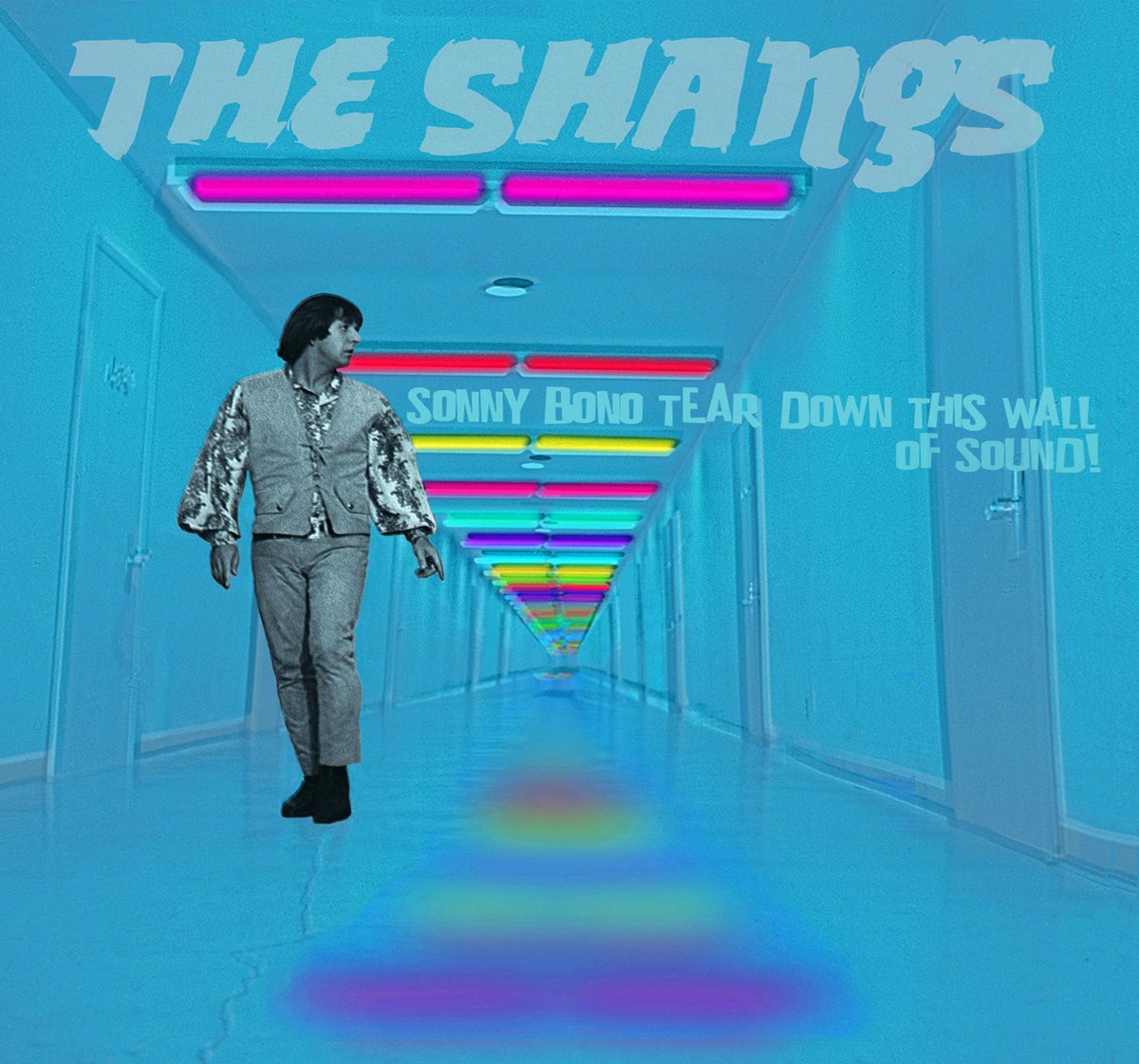

On The Shangs’ Facebook page, the Canadian band refers to itself as “Mystery Pop,” and it’s a spot-on descriptor. So much about their new album, Sonny Bono Tear Down this Wall of Sound invites questions that the tracks don’t answer starting with “What is this?” The band, its catalogue, and the new release all exist outside of clear musical contexts. The title, for instance is clever, but the music is not that facile. The album is indie, but that only really answers financial questions. The songs are psychedelic in an early Pink Floyd and German kosmische musik mode, but they’re grounded in American pop culture and not space or the British countrysides that invite dreams of gnomes. The liner notes point to the Hamilton, Ontario pre-punk band Simply Saucer that Shang Dave Byers played in, but if you don’t know Saucer, that reference doesn’t help. And since he’s not on Cyborgs Revisited—the band’s defining release—that too leads to more questions than answers.

Fortunately, Sonny Bono … is a puzzle box worth exploring. The songs establish rich sonic landscapes and go on long enough for the movement inside those tracks to become not only evident but engaging. The layers of guitars and ambient loops never feel static, and while Byers and fellow Shangs Ed and Pat O’Neill let the instrumental passages be the focus, the music holds up without solos or showy bits to move into the spotlight. Songs drift by at a luxuriating pace and are consistent with the previous Shangs releases—Longet, A Little Bit of Semi-Heaven and Golden Hits of The Shangs—but they present the band at its most robust and muscular. Sonny Bono … isn’t a forceful album, but there are tracks on the earlier albums when the delicate stillness is so palpable that you can see the dust motes floating in the light of the setting autumnal sun in your grandmother’s sitting room, and that’s not the case here. Instead, the lo-fi production achieves the same effect as high contrast black and white photos on cheap newsprint, making things seem real and distorted at the same time.

On “Eleven (Eleven They Will Never Solve),” the opening track, that manifests as a tangible atmosphere of electric dread that registers immediately. The song further documents The Shangs’ fascination with the Manson Family murders and includes found audio by the female members, none of which is obvious if you don’t have the liner notes. Still, the darkness is as palpable as the song is engrossing. “Eleven” is the most fully realized track on the album, but even the more skeletal tracks draw you in. “Silk and Ivory” requires that Byers deliver a slow-moving melody that sometimes comes up “pitchy,” but those moments turn a flashlight on another mystery. Are they simply missed notes, intentional, serrated choices, or happy accidents? They certainly seem to be of a piece with Sonny Bono … as a whole. The mid-to late 1960s clearly fascinate The Shangs, and in particular the places where glamor and damage intersect. “Silk and Ivory” was written by Craig Smith, a child actor who became an acid casualty when his adult career never quite came together. “High Noon” was inspired by the murder of the father of The Lennon Sisters, a vocal group that became famous on the easy listening Lawrence Welk Show, and “Queen Mindy and the Athena Complex” is a shout out to The Feminine Complex, an all-girl group from Nashville that inspired Byers and the O’Neills. On the song, they feature the voice of The Feminine Complex’s Mindy Dalton on a phone call.

Again, little of that is clear without the liner notes, which is an argument for pursuing a physical copy and not simply streaming or downloading the album on Bandcamp. But once you know, then what? Knowing the story behind “Eleven” doesn’t explain the song or The Shangs’ fascination with the Manson Family. A lot about Sonny Bono … and The Shangs’ music in general isn’t a mystery as much as it’s simply private. The album has space rock moments and bossa novas, and they fit together even if the logic isn’t obvious. My suspicion is that they come from different impulses—one from the pleasure of playing with other friends, some of which were bandmates in Simply Saucer, while “(Lying Here) In Brazil” connects to the band’s fascination with a moment when the Sixties seemed to be on the verge of something unprecedented almost daily.

That kind of privacy may not work for everybody, and it certainly seems like the opposite of the pop impulse. For me, it makes Sonny Bono … and The Shangs more interesting as the tracks make clear that artistic, personal and professional motivations could all be at work at any time. You hear real people making choices, even if you’re not sure you understand why they made them. Are The Shangs inscrutable? No, they’re inscrutable-ish, but none of the choices they make are the ones a boardroom would make. The real mystery in The Shangs’ pop is how anyone ever hears their music as a stand-alone sonic event.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.