The Vettes Lose Context on "Gold Star"

The River Ridge band's new album reveals some basic truths about pop.

In 2008, The Vettes’ “Give ‘em What They Want” got airplay on B97, and you could imagine the song finding the band a national audience. It didn’t happen, likely for a number of reasons that had nothing to do with music, but it didn’t help that The Vettes’ ‘80s new wave-influenced dance rock wasn’t in style at the time. That year also gave us Sara Bareilles’ “Love Song,” Lil Wayne’s “Lollipop,” Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl,” and Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida,” all of which were on a different musical page.

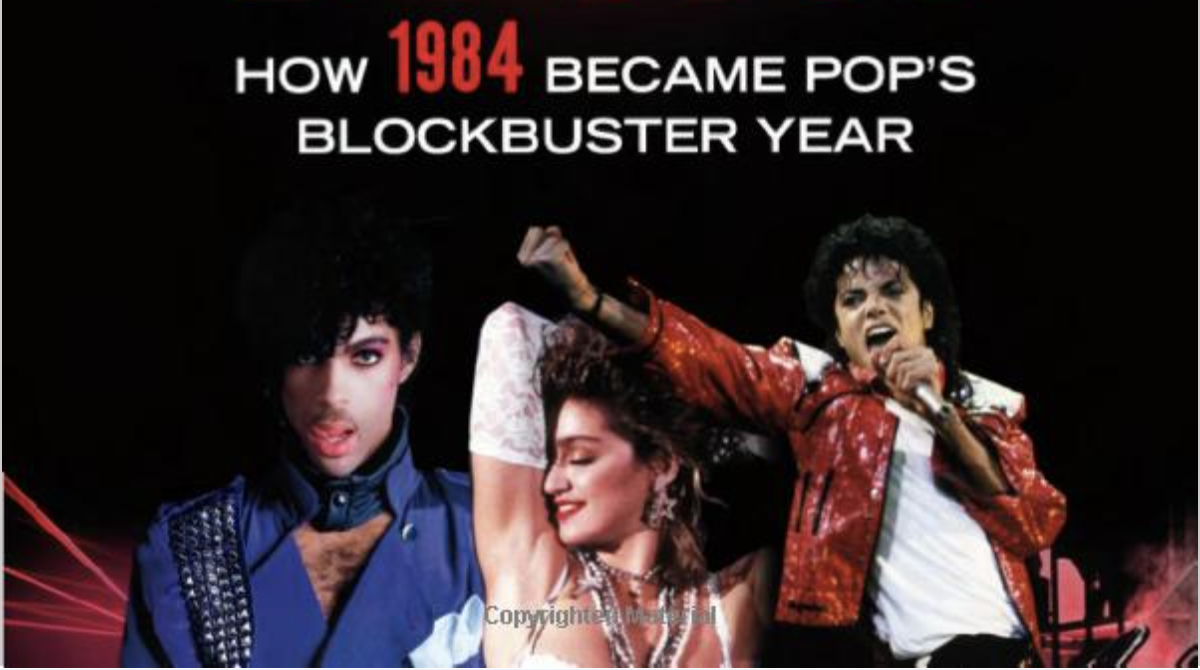

In 2010, the band released Plasticville, which followed up on the musical promise of “Give ‘em What They Want,” but not the commercial one, so The Vettes’ new Gold Star doesn’t come with same air of possibility. That doesn’t diminish the album, but it does affect how we hear it. New wave matched with EDM’s hairy synth textures that once made sense when heard in terms of how they fit into the pop marketplace don’t live in the same context anymore. Now the Lady Gaga influence is a reminder that The Fame Monster came out in 2009 and that she’s been through a few identities since. Without the pop marketplace as a context, we’re left with an album of songs that simply sounds familiar.

The Vettes play French Quarter Fest Sunday at 2 p.m. on the GE Digital Big River Stage, and their songs remain catchy. “Hard Way” addresses prescription pill abuse with gallows humor when Rachel Vette cavalierly sings, “Overdose and comatose is no big deal,” and “Survive the Night” has the ease of a Duran Duran song because it sounds like Duran Duran songs. The band members are clearly pop fans, so it’s no surprise that their songs would work.

Some work better than others, though, and I’m not sure “Flip the Bird” would get across in any era. Sometimes your middle finger really can say all that needs to be said, but that doesn’t make it a good song idea. Similarly, remaking LeRoux’s “New Orleans Ladies” as “New Orleans Lady” with U2 guitar and percolating 808s updates the song sonically, but the relationship between Rachel Vette, the band, and woman or women being sung about—the pronoun in the chorus remains plural—is unclear. If it is a gesture toward the marketplace—people like remakes—it’s one that suggests they’re not paying attention like they once did.

Onstage, The Vettes have always dressed for the gigs they wanted more than the gigs they had and played the roles of the stars they hoped to become. Songs that made their goals seem possible helped, but without Potential acting like the band’s sixth member, The Vettes seem more conventional.

The bottom line is that pop is a high stakes game, and good ideas in one context are less convincing when the pop world shifts. It doesn’t change the music, but it changes how we hear it.