Last Night: 20 Years Between Beck Shows in New Orleans?

Sunday night's sold-out show at the House of Blues raised a good question as to how Beck could go 20 years without playing New Orleans. With photos by Patrick Ainsworth

Sunday night, Beck played the House of Blues, playing a rare club show between weekends headlining the ACL Festival in Austin. My review of the show is online now at The New Orleans Advocate, but I had a few thoughts that didn’t fit in that story that seemed worth bringing up.

- Beck announced that it was his first show in New Orleans in 20 years, which was amazingly true. He played The Boot shortly after the release of Mellow Gold in 1994, and that was it. He explained that people said he couldn’t sell tickets in town, and while I rarely take what musicians say onstage at face value, there’s something to that. In general, New Orleans has had a reputation as a bad city for rock bands, and emerging bands that could sell out a room in Baton Rouge sometimes played to 10 to 20 people at the Mermaid Lounge in the ’90s.

Thankfully, it looks like that’s changing, but still—after a certain point, it’s hard to believe that the logic was as simple as that. After the release of Odelay, he could have done very well if not sold out Tipitina’s and the House of Blues if not bigger venues. There’s something else in the mix.

One of the impacts of the post-Katrina flooding that might also factor into his absence was the loss of 2,000-seat venues, which appear to be the sort of rooms he plays around the country. In 2008, Tom Waits played Mobile, Alabama on a tour that surely would have stopped in New Orleans if we’d had a Saenger, Orpheum or Mahalia Jackson Theatre for him to play.

- One thing I touch on in my review is the distance Beck creates from his audience, whether it’s through his deadpan look, his wry stage patter, or lyrics that ward off clear meaning. There’s something very endearing about him despite that, and where I was by the side bar, there was a feeling of warmth and community despite being wedged in. I attribute that to Beck and not simply the occasion. People weren’t simply happy to see him there; they were happy to see him.

Where I stood, that also translated to a remarkably respectful listen to the quieter first half-hour, though The Times-Picayune’s Keith Spera says it wasn’t as quiet by the back bar. Maybe I just had a good crowd around me.

- During “Sexx Laws” in the encore, Beck took a moment to say that he wasn’t playing to tracks and that everything was live. These days, tracks are more common than we realize, and there were a couple of moments where I wondered if Beck had some because he backed away from his mic as a sung note hung longer than I thought it should. During “Sexx Laws,” I heard a baritone sax part in the mix but didn’t see one and again wondered if it was canned. After he pointedly raised the issue and credited the band, I figured he likely wasn’t and realized that one of the three guitarists on stage was slurring a note on the low E-string to create the bari sound.

The music nerd in me was impressed that the band included Roger Manning and Jason Falkner from early ‘90s pop band Jellyfish. There was nothing Jellyfish-like about Beck’s arrangements, but it still cool on the “Those are the Jellyfish guys!” level.

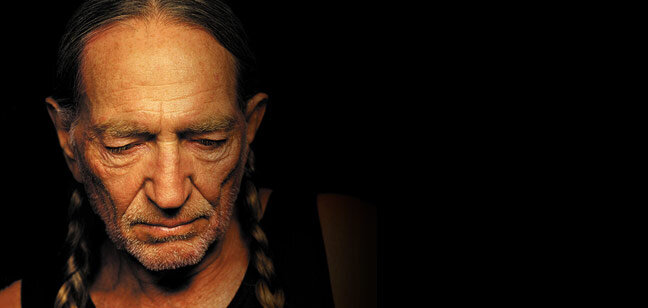

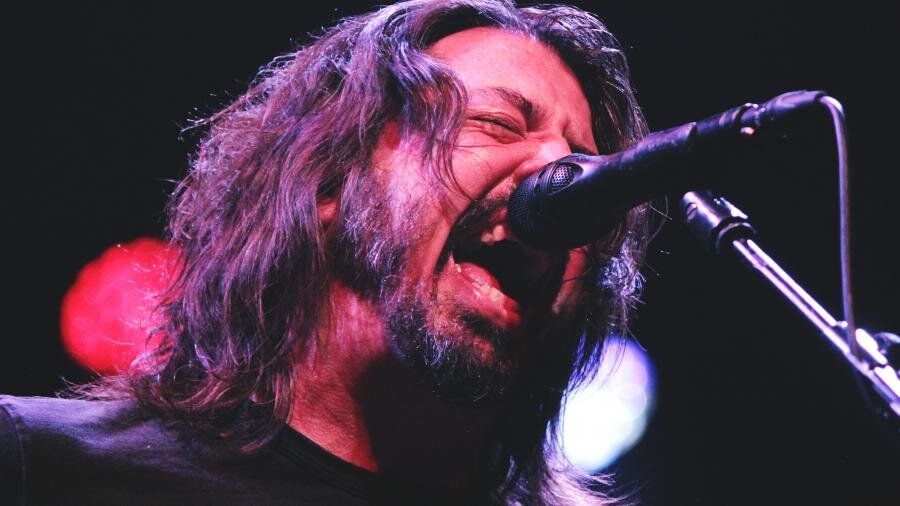

- Photos don't entirely do justice to the show. Photographers were allowed pit access for the first three songs, which is standard procedure for acts of a certain size. In this case though, it came during the acoustic Morning Phase/Sea Change part of the show, so Patrick got good shots of the folky, contemplative Beck, but pictures of the tent revival preacher Beck and the pop-n-lock Beck and the rock star Beck exist only on iPhones and Androids in the pockets and Instagram feeds of fans. Maybe that's how it's supposed to be.