Last Night: A Journey Through the Past with Willie Nelson

The LEH's Brian Boyles saw his family's past in Willie Nelson's show at the House of Blues Sunday night.

The LEH's Brian Boyles saw his family's past in Willie Nelson's show at the House of Blues Sunday night.

[Brian Boyles is a long-time friend of My Spilt Milk, and last weekend he attended Willie Nelson's show at the House of Blues. Here's his report.]

My mom is 71. She’s coming off a bout of bronchitis, and the brief, bitter New Orleans winter isn’t helping any. But here we are, waiting in line outside the House of Blues to see Willie Nelson. As we wait, we talk about the different reasons we have for being excited to see Willie. Willie Nelson means a lot to us.

I turn 40 this month. The first concert I attended was Willie Nelson at the Civic Arena in Pittsburgh. I was around 4 years old, and I swear have vague memories of being surrounded by cowboy boots. When I was 7, my family moved to Austin. Ostensibly this was to escape the cold, but the music of Willie and the Outlaws movement surely influenced the decision. Another early memory: riding in my father’s dump truck listening to Waylon Jennings and Jesse Coulter singing Elvis’s “Suspicious Minds.”

Inside, I position my mom as close to the stage as possible (along with my musical tastes, I also get my height challenges from her), then head to the bar, where I double up on the whiskey. Good crowd tonight. They respond positively to tonight’s opening act, Runaway June, a nice sounding trio of young women, one of whom is identified as the granddaughter of John Wayne, which seems somehow fitting in this psychedelic season in American symbolism where everything appears both fitting and alarming.

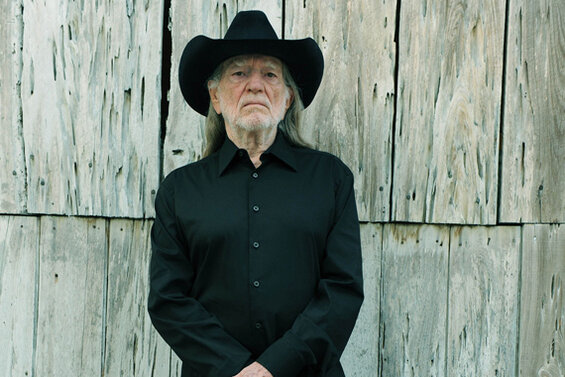

Willie and the Family take the stage, though, and all is right with the world. Mom and I are within 20 feet of a central figure in our shared memory, and when he begins the set with “Whiskey River,” my mom lets out a full-scale teenybopper scream. We agree that seeing the assassin-faced Paul English is super amazing, too.

My dad was roofer. We’d been in Texas maybe a year when he got contracted to do some big houses on Lake Travis, which was experiencing a boom at the time. His crew was made up of Mexican men in the country illegally. My dad treated them fairly and we’d hear stories of their exploits at dinner, how they wrapped their legs around the sides of the ladders and slid to the ground. How the women delivered tamales and tacos every day for lunch, which my dad loved.

One day my dad walked into the house we rented with a huge smile on his face.

“Who wants to shake the hand that shook the hand?!”

He’d been on the roof when one of the crew came to tell him a man was looking around the house. The man had emerged from a beat up pick-up truck, and when my dad first caught sight of the dusty figure, he thought maybe then man had been sleeping on the job site.

As he got closer, my dad realized it was Willie Nelson. They shook hands and Willie said he was looking to buy a house. The rest of the short visit was blurry for my awestruck dad. When he came home, we all shook his hand, and then he put a bag over it and showered, careful not to wash off the magic Willie dust.

At House of Blues, Willie pivots “Funny How Time Slips Away” into “Crazy.” I recall being a teenager when Ross Perot was running for office. He used “Crazy” as his theme song, and during a broadcast of one of his campaign appearances, a broadcaster purred, “Patsy Cine’s ‘Crazy,’ a song she wrote for him.” Fifteen-year-old-me was pissed at all the inaccuracies.

Think how quaint was Ross Perot compared to what’s at hand.

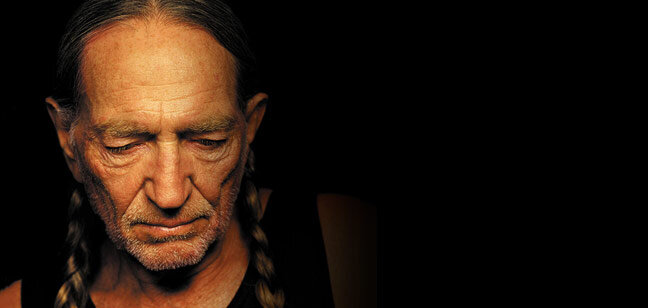

My mom and I can’t get over how close we are to Willie. I try to pay most of my attention to his guitar playing, as I’ve never had such a good view. He is not as dexterous as he was, but it’s still spellbinding. For me, Willie is in that Neil Young class of independent guitar heroes, someone playing by his own code. Willie Nelson calls on so much of American (and, I think, Mexican) guitar history, but think: who else sounds like him? So to see him on that acoustic guitar, within 20 feet, was to watch the master in his late, late autumn. And let me tell you, at 83, he fucks around with time, playing all around the beat, making the band chase him, drifting into himself for moments when, it appears, he’s asking the guitar for something more, another run.

He performs a brief “Whiskey for My Men, Beer for My Horses,” the post-9/11 song he did with Toby Keith. Think how quaint was Toby Keith compared to what’s at hand. “We’ll raise up our glasses against evil forces….”

In 1999, for my last Jazz Fest of college, I came into a supply of children’s tickets, $10 apiece. This was quite a score for an undergrad, even when full price was something like $25. I’d been seeing a girl for a few months and, like a big shot, offered to take her to see Willie Nelson with these sketchy tickets. I was shocked to learn she’d never been to Jazz Fest in her four years at Tulane. There was a problem, though: she was on the organizing committee for the year-end fair held by Newcomb College, scheduled for the same day as Willie’s Jazz Fest set. She was expected to attend.

“C’mon!” I pleaded. We went. I showed her the kid’s tickets and told her we’d go through the line overseen by the oldest-looking ticket-taker. It worked. We saw Willie, and he was great. And that’s my wife.

Back to Willie and time, as in the present and tempo. If there’s any doubt as to him fucking around like this tonight, rather than simply being out of sync with his longtime band mates, it’s dispelled when he begins “Always on My Mind” solo and does the same creative conversation with his guitar. Also, holy shit the bridge on that song. “Tell! Me!” Also, there simply may not be a better song than “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground.”

These songs lead to “Georgia on My Mind.” Willie won a Grammy in 1979 for that song on the Stardust album. The last time I saw him, in August 2013 at the Hollywood Bowl, he covered the full album with the L.A. Philharmonic. We were visiting my childhood friend in Los Angeles, and my wife was pregnant with my son. She went to dinner with another friend, so my pal and I downed a bottle of wine at the gate. This was when I started thinking about Willie and time, and Willie as Chaplin, a performer who emerged out of traditions to birth his own modern figure. There were times when he and the orchestra got near-seriously out of sync, but the thing was, Willie wasn’t the one who was off. With that material, after all this time, Willie can never be the one who’s off.

His pop success came when he reached back into the classic American songbook, and almost 40 years later, he is one of our living last connections to that songbook. He performs Hank Williams for us with some of the only first-hand authority left on the planet. It begins to settle on me, now, that I may not see Willie Nelson again.

And so I relish the instrumental interlude, when the band slows down and Bobbie Nelson is freed up. Willie’s younger sister and longtime pianist, she keeps a poker face under her hat and just enough jump in her playing. I remember the inside cover of my parents’ Willie and The Family Live album, a spread of the entire crew, not just the band but whoever else they could fit into the photo.

Last memory: When I worked in midtown Manhattan, I’d take long walks during the lunch break. My office was on 45th and 6th, and one day I found myself walking back from Central Park on Broadway. Coming up the sidewalk? Willie Nelson, with a blonde woman on each arm. “Willie!” I sputtered. “Hey, hey,” he said, not breaking stride. I called my mom and then my dad. I’d seen Willie Nelson.

Tonight Willie’s face at close range is, more than ever, a familial one. I know bags and creases like that. I have seen the road on the forehead of an old man before. He does “All Going to Pot” for Merle, does “Good Hearted Woman” for Waylon and, we both understand, for my mom. And we sing “Mama’s Don’t Let Your Babies” loudly at each other because we both know that, whatever I am, I didn’t turn out to be a doctor or lawyer or such, nor did I descend from any.

The night closes with “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” and “I’ll Fly Away,” a jubilant, but departing-spirit goodbye. There is a slight remove that any man in his 80s holds. The present is surely a good point for an outlaw to exit. And in this strange time, to see Willie Nelson wave farewell to the crowd, to me and my mom....

We’ll miss him.