For Bounce DJs, These are the Breaks

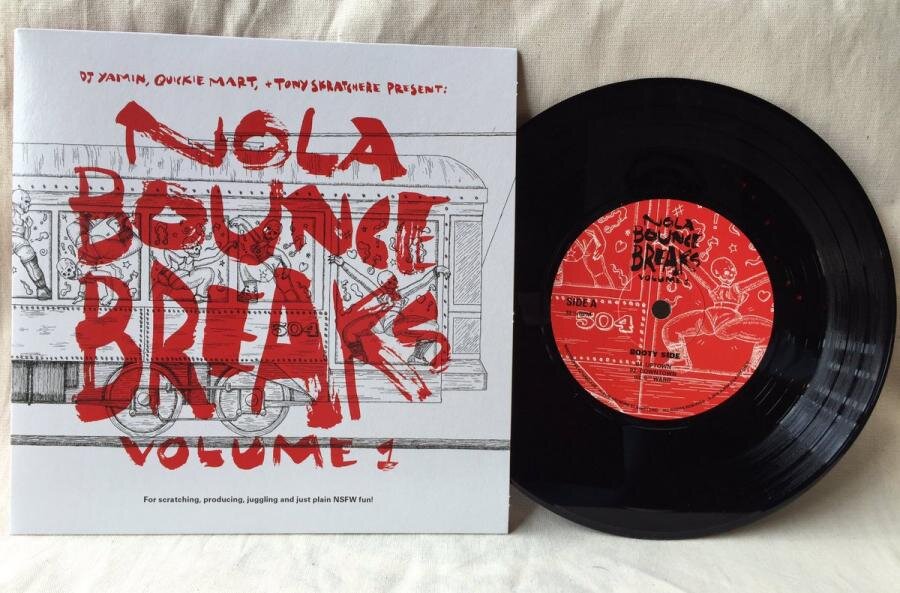

"NOLA Bounce Breaks Vol. 1" pulls together the essential breaks for DJs who who want to add them to their turntable repertoire.

Since the 1979 release of Super Disco Brake’s Vol. 1, entrepreneurs have collected mandatory hip-hop breaks to save DJs the work of tracking down and buying all the source records. Winley Records may not have had any more claim to songs by New Breed, The J.B.’s and Dennis Coffey than it had spelling skills, but that album and three subsequent volumes compiled tracks with the most in-demand breaks among DJs. In the mid-1980s the Ultimate Breaks and Beats series made life easier still for DJs by isolating the breaks, then the turntablism boom in the ‘90s led to an explosion of breaks records that made it easier for DJs to have an arsenal of samples for scratching at their fingertips.

“Between the three of us, hundreds of scratch records,” Tony Skratchere (Ben Hebert) says.

New Orleans DJs Skratchere, Quickie Mart, and DJ Yamin put together NOLA Bounce Breaks Vol. 1 with a similar goal. The 7-inch, limited edition EP pulls together crucial samples, many of which are on records that are now almost impossible to find. For bounce, these samples are important because for those with an appreciation for bounce’s history, the defining characteristic of bounce is the presence of the “triggerman beat” or one of a handful of other samples. Tempos and levels of percussive clatter can change, but purists believe that without the triggerman beat, the “Brown beat” or the bones sample, it’s not bounce.

Skratchere and Quickie Mart (Martin Arceneaux) have all these samples on their computers and have done countless bounce remixes with them, but despite his years of love of bounce, Skratchere doesn’t have all the EP’s breaks on vinyl.

Like Winley and probably everybody who has released a breaks album before them, Skratchere, Quickie Mart and Yamin’s legal claim to the music is dubious. One of the obstacles bounce has faced reaching a national audience is that its core samples have rarely been cleared so the records could only be sold locally and the music can’t be compiled by a Rhino or a Light in the Attic without exposing artists to potential lawsuits. NOLA Bounce Breaks Vol. 1 is a deliberately limited release, and the DJs aren’t taking any money out of the project.

“The profits go the bounce artists that I recorded for the vocals because most of those vocals are original from sessions I did with them,” Arceneaux says. “The rest goes to making another one. It’s helping to keep bounce going in more ways than one. A lot of these artists are heavily exploited by outside dance music forces that aren’t in the city and can’t give a shit about New Orleans.”

The market for the EP is first and foremost DJs. Finding a good starting place for your bounce collection may be tough to do, but NOLA Bounce Breaks Vol. 1 isn’t it. “It’s records as tools,” Hebert says. “It’s not for playing but for playing with. They’re records for scratch DJs to use.”

One side collects classic bounce percussion loops, and the other is three scratch “sentences”—“words or sounds strung together on a click track at the same BPM as the other side of the record,” says Yamin (Ben Epstein). With two copies of the record, DJs can have one on each turntable and scratch bounce percussion loops over bounce a cappellas—isolated vocal tracks.

“It makes bounce accessible for someone from New Orleans or anywhere,” Epstein says.

Skratchere hopes the record helps people get a better understanding of bounce. Mannie Fresh and Juvenile came from bounce, but most of their output isn’t strictly bounce. For many outside of New Orleans, Diplo’s “Express Yourself” with the late Nicky Da B and “Beats Knockin" with Fly Boi Keno or Big Freedia, “because those are the international acts,” Arceneaux says.

Around the country, bounce is still exotic. Skratchere grew up hearing it in New Iberia and Quickie Mart heard it as far away as Shreveport, but bounce never seemed to cross the Louisiana border until recently. Quickie Mart attributes the inroads it has made to electronic dance music, which it has a lot in common with these days. “It’s not quite hip-hop and it’s not quite dance music, so it can appeal to both people,” he says. “That’s really helped Freedia. Freedia is the Queen of Bounce and she can hold that title, but some people don’t think that’s bounce. They’re unfamiliar.”

The affinity between the two sounds led to the development of an EDM brand of bounce—“twerk”—but it is also a relatively recent development. “Right around the time of the storm and right after, bounce music changed,” Hebert says. “Cats like Blaza and Pikachu and producer BlaqNmilD came in and completely changed the sound. They sequenced it differently, they chopped it up differently, it was harder, it was more aggressive.” Their work has become the sound that people associate with bounce, if they associate any sound with it at all.

NOLA Bounce Breaks Vol. 1 is, as the name suggests, the first in a series. The next volume is in the works and they plan to do three.

“The Star Wars trilogy of bounce records,” Hebert jokes.