Back to the Birth of Bounce

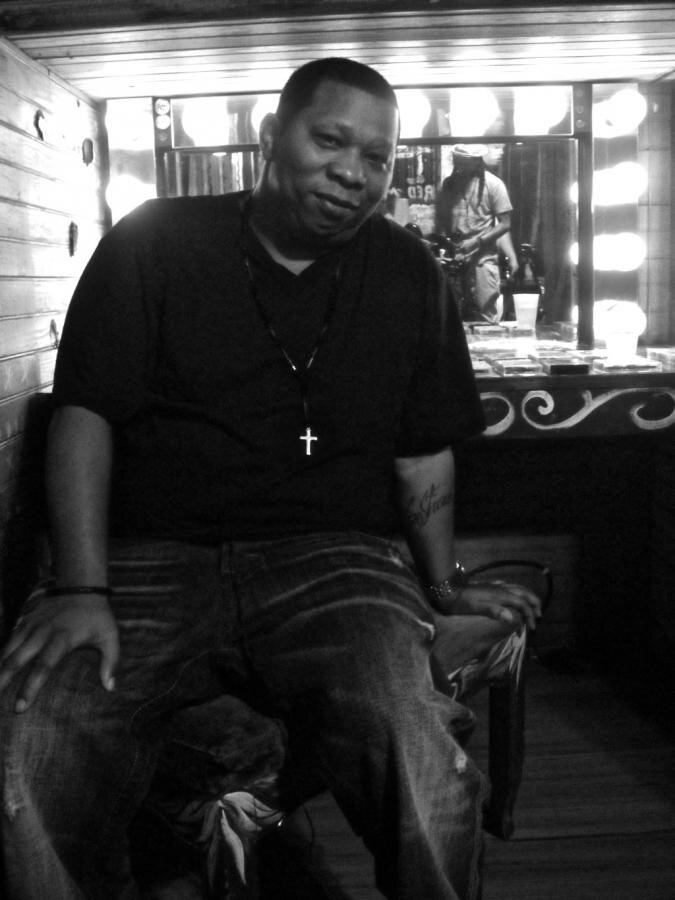

In "Ya Heard Me" and "Bounce," Matt Miller has spent much of the last decade documenting the New Orleans hip-hop phenomenon.

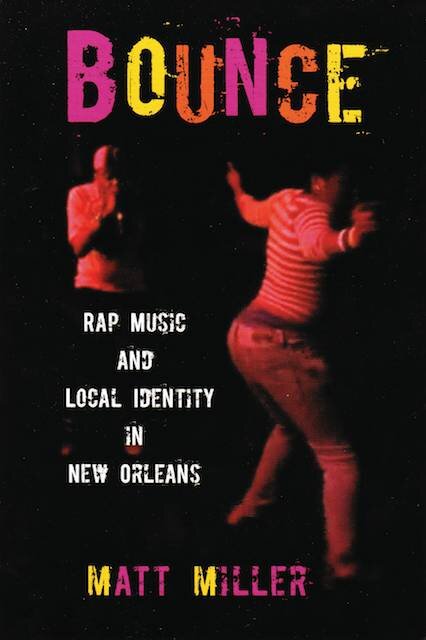

Telling the ending won't ruin this book. "Whether or not bounce persists as a local subgenre marked by particular musical and lyrical preferences and values," Matt Miller writes in Bounce: Rap Music and Local Identity in New Orleans, "the more abstract notions that informed it - collective celebration and a spirit of resilience and creativity - will continue to be crucial tools for the psychic survival of African Americans in New Orleans and will doubtlessly produce innovation and influential musical expressions in the process."

The book, published by the University of Massachusetts Press, is an expansion on Miller's grad school dissertation, and it recounts New Orleans' hip-hop history with a strong emphasis on bounce. It's a topic that became an obsession of the Atlanta-based Miller's when a bandmate visited New Orleans in the late 1990s and brought him DJ Jubilee's "Jubilee All" single, which he had found in a dollar bin. "We were fascinated by it," Miller says. "Wow, this is totally different from anything going on around here or on the national rap scene." Another friend moved to New Orleans and started sending him tapes of shows on Q93, then in 2001 Miller and his wife came to New Orleans for Jazz Fest, where they first saw DJ Jubilee, as well as a number of the artists on Take Fo' Records. Seeing it made him think of a documentary on bounce.

"I developed a taste for the music and spent a lot of time peeling back the different layers of the scene and trying to track down a lot of the music," he says. "At the same time, I started to become obsessed with the music of New Orleans in general."

Before Miller wrote Bounce, he made the documentary he envisioned on that trip. He started shooting it without a clear plan, though. "Let's do some interviews with DJ Jubilee and film some of these live shows," was as far as he'd thought it through. "Seeing [bounce] work live made it make sense in a way that listening to without having any experience of what it does in live setting [didn't]. It's party music like a lot of New Orleans music. It's well-crafted party music, and they know a lot about how to work with a crowd."

Miller had no background in film, but he got with a friend who had experience, and they came to New Orleans to shoot what they could. On their first day, they interviewed Jubilee, then he took them to a block party that he was DJ'ing in the Melpomene. "That got huge," Miller says. "Katey Red and Freedia were there. That was sort of a crucible experience, and we started with that. We learned about other parts of the scene that were still going on contemporaneous with Take Fo' in the early 2000s, and the historical parts of it. We started asking about where the style started, and Oh, T. Tucker's the father of it. Where is he? Nobody seemed to know. It was a fast-paced music scene, and a lot of people were interested in looking forward."

He eventually located T. Tucker, along with many of the bounce pioneers, and ended up with the film Ya Heard Me, which was essentially finished in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina hit. "You can't have a movie without talking about Katrina," Miller says, so they shot follow-up footage over the next two years, including an interview with bounce pioneer DJ Jimi, who was in Central Lockup when Katrina hit, and footage of a pre-Katrina block party juxtaposed with shots of the same block, abandoned and overgrown, after Katrina.

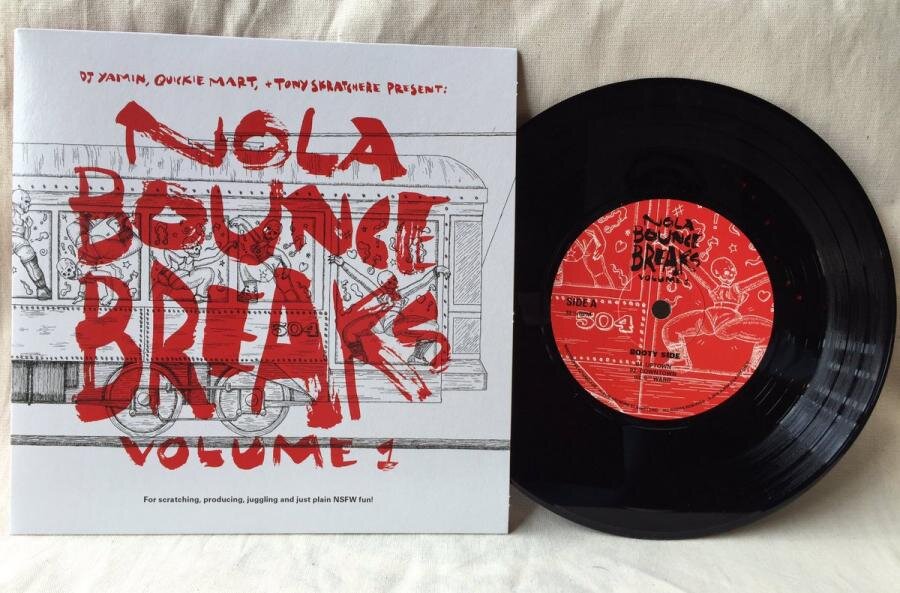

In Ya Heard Me, rappers and DJs talk about the importance of the "triggerman beat," and how one of bounce's defining characteristics is a triggerman sample. They're referring to samples from The Showboys' "Drag Rap" from 1986, and while it wasn't a national hit or a regional one in their native New York, it caught on in New Orleans and Memphis, and became an essential part of bounce's DNA. When Tony Skratchere, Quickie Mart, DJ BlaqNMild and others recently made bounce remixes of soft rock tunes, they did so by marrying the hits of the '80s to a triggerman sample. "It's more like an instrument than a recording," Miller says, but those samples became a major problem when it came time for Miller and his partners to secure the necessary clearances to include much of the music in the film.

"We were trying to deal with [the song's publisher] Warner/Chappelland get them to give us a blanket clearance for the material that's in the film that uses that," Miller says. "People never got permission, and [Warner/Chappell] wanted a list of people who used it, which we didn't want to give them. We wouldn't want to expose anybody else to financial liability in that regard." That stand-off means that the song's samples remain uncleared and the film can't be screened without exposing Miller and the producers to legal action. It showed in New Orleans in 2008 at Zeitgeist Multi-Disciplinary Arts Center as part of the Human Rights Film Festival, and when it's been seen, it has been shown as part of film festivals under festival licenses.

Miller and his partners are considering their options. It's impossible to do a film on bounce without the triggerman sample, and it will be a lot of work to re-edit Ya Heard Me so that the recorded music conforms to fair use standards. He's considering breaking the material out into shorter segments for YouTube, but nothing is definite. "Hopefully there's still another last transformation that's going to happen that will let the great stuff that we captured back then be seen," he says.

His experiences working on the documentary provided the groundwork for Bounce. "Talking to people in New Orleans as part of the film project was essential in terms of getting started, and then I tried to do a lot of supplemental research with recordings and old press coverage to try to tease out a more complete picture of what was going on. I started writing and researching about New Orleans pretty soon after we started the film, so the two projects, book and film, really operated in a synergistic manner."

In Bounce, Miller establishes a historical context for hip-hop that goes back to Congo Square and includes sections on No Limit and Cash Money, both of which became the New Orleans hip-hop stories along with Mystikal in the 1990s. Aside from a few important releases, No Limit owed far more musically to Tupac Shakur and West Coast rap than bounce, and Mystikal's hits revealed his ambivalence toward the sound. Cash Money releases moved on from bounce's core musical vocabulary, but its connection was clearer.

"Some of it was foundational bounce material, from the style of the lyrics to what they're talking about to the music laid down behind it," Miller says. "From Lil' Slim to Baby's initial release under the name B-32." In his estimation, early Cash Money had many of the most talented bounce artists, but then it moved toward a more stripped-down sound. Mannie Fresh's productions leaned away from samples and toward originally played instruments, and the lyrics became more gangsta.

"With 'Ha!' and 'Bling Bling,' they found a way to bring bounce energy into a more polished product that shook up the national rap scene. Stylistically, they started a lot of big ripples with that stuff. It wasn't exactly bounce by that point, but it wouldn't have been what it was without the background of bounce. Mannie Fresh - it's hard to underestimate his influence on bounce. So many of those early recordings are classics. Him and J. "Diamond" Washington and DJ Precise."

One thread that runs through Bounce is how consistently the press missed the music. In 1998, The Village Voice's Barry Michael Cooper mistakenly assumed that No Limit releases were representative of bounce and, as Miller observes, "describes 'the unique sound of N.O. bounce' as 'funerary' and 'slowed down to a heroin nod.'" Closer to home, Miller points out that with the exception of OffBeat's Karen Cortello, local critics generally decided that the lyrically stripped down, party-rocking bounce lacked the subtlety, intricacy, and potential of nationally successful hip-hop.

"There are ways where [the critics'] perception of what was going on at the time was not totally accurate, but that's the difference between journalism and scholarship," Miller says. "Journalists don't have the luxury of waiting until the dust settles to go back and say, Now what really happened?"

Matt Miller's Bounce blogspot includes mixes with songs that are mentioned in each of the chapters. It's a good place to start to hear bounce since much of it is out of print.