The McCready Concert Moves, And Drive-Ins Become the New Concert Halls

Marc Rebillet, coming soon to a drive-in near you.

The first efforts to stage live music events take a detour to Missouri and end up at the drive-in.

[Updated] The proposed Travis McCready concert in Ft. Smith, Arkansas started as illustration of what future concerts might look like. The improbable show was scheduled to take place last Friday, May 15, but because Governor Asa Hutchinson had not yet opened the state for public gatherings, it was “postponed” against the promoter’s will. At first, the show was fascinating as an exercise in problem-solving that previewed a number of precautions that will likely be a part of any live music performances that take place this year, assuming any occur: Mandatory temperature checks, face masks, and dressed houses with patrons in socially distanced clusters in venues filled to only 20-30 percent of capacity.

Once Hutchinson pointed out that Arkansas was still under a stay at home order, the show’s story became a different, far less interesting one.

Promoters Temple Live continued to sell tickets after Hutchinson’s announcement, so the state stepped in on Thursday night and pulled the venue’s liquor license, which in effect forced the cancellation. Without the bar, there was no way the venue could make money on a show that was already going to have a thin margin with the reduced capacity. At that point, the concert became another battleground in the culture war that is the Trump Presidency. “‘We the people,’ three amazing words, and they have been trampled on today,” Temple Live representative Mike Brown said during a televised news conference.

Like anti-maskers, the promoters cast themselves as defenders of American freedom in cartoonish terms, as if anything other than absolute, unconditional freedom equals totalitarianism, and anyone who doesn’t agree with them hates freedom. Brown gave the game away when he complained that churches could have gatherings of larger than 50 people and he couldn’t. “We are not trying to be difficult,” Brown said on Wednesday. “We just want to be treated fairly and with respect.” The issue wasn’t really freedom; it was that somebody was getting something he wasn’t getting. That complaint lines up with the way culture battles are fought today with the winner being the one who feels the most aggrieved (which is not the same thing as actually being the most aggrieved).

On May, May 18, Arkansas took the first steps to reopen commercial activities, but the state caps gatherings at 50 people—less than a quarter of the audience that bought tickets to see McCready. Temple Live moved the show two hours from Ft. Smith to the grounds of the Tall Pines Distillery in Pineville, Missouri, a state where Governor Mike Parson greenlit concerts starting on Monday, May 4. It will now be an outdoor concert on Tuesday, May 19, and patrons are told that “Social distancing is required.” There are no details of what measures beyond that request will be taken to make the space safer.

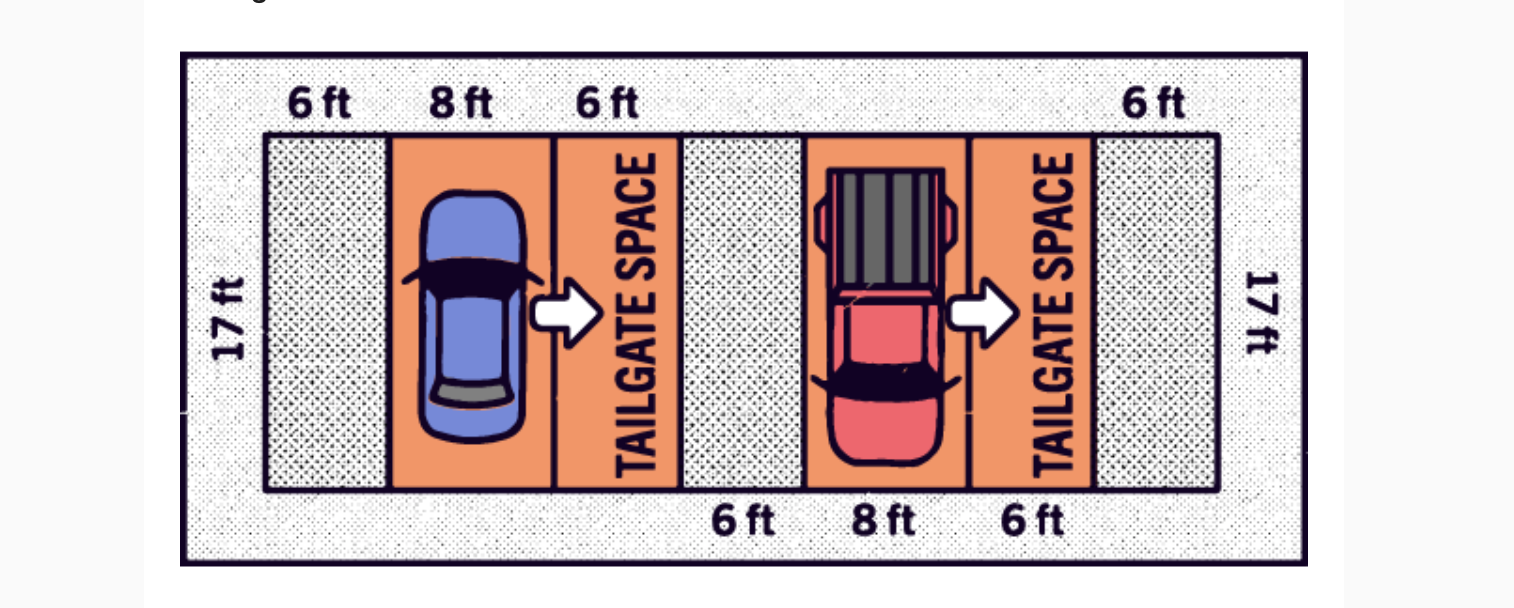

The Travis McCready concert was of interest because it presented a vision of what concerts might look like in a COVID-19 age, but it’s not the only vision. Drive-in concerts are also gaining some traction. On the weekend, Keith Urban played a show at a drive-in theater outside of Nashville for medical first responders, and similar shows up have popped up around the country. Cars and the broad expanses that parking lots and drive-in theaters allow seem like a promising way to socially distance fans at live music events, but Urban and many of the early test cases attract audiences that by age or disposition are more likely to keep their distance as they sit in their cars or in folding chairs beside them and listen.

A better test of the concept will come in June when electronic dance music artist Marc Rebillet plays a series of drive-in shows in venues from Maryland to Colorado to Texas. Will a young, dance music audience stay safely in their cars as the music is piped into their radios? The crowd didn’t when a West Bethlehem, Pennsylvania restaurant hosted a drive-in concert with two acoustic guitar players. Still, people are experimenting with the idea around the country, and major promoters Live Nation will present four drive-in shows in Denmark with a family-oriented show to increase the odds of cooperation.

Drive-in shows solve the social distancing problem by putting a car chassis around it, but that solution works for specific audiences in parts of the country that have strong car cultures. A social media poll of 1,000 attendees of New York City’s Electric Zoo electronic music festival and dance music events promoted by Made Events found that 38 percent of respondents said they wouldn’t attend a drive-in show, worried about the environmental impact, bathrooms, and drunk driving. A voluntary online poll with a relatively small number of respondents has clear limitations, but the poll suggests that the idea is a partial solution at best.

It, like all live music in the near future, is likely to come at a cost. The reduced capacities will drive up costs at drive-in shows, as will efforts to maintain a healthy environment in non-standard venues, many of which don’t have liquor licenses. Rebillet’s tickets usually cost in the $20 range, but on the upcoming tour, they will cost $50 per person with a minimum of two per car.

“The margins are very thin,” Rebillet told Bloomberg’s Michelle Lhooq. “We’re hoping people are willing to pay a premium to be around each other, and are banking on them buying merch and concessions. Still, it’s not my most profitable tour.”

These concert options represent efforts to circumvent one of the central and most appealing features of concerts, sporting events and public events—their communal nature. The point is to be around other people and to share moments together. There’s something beautiful about being in a space and seeing the broad spectrum of people who connect to it, or, conversely, being at a show and feeling with a fair degree of assurance that everybody present shares values with you. You’re with your people. The fan pods, drive-in concerts, and other ideas yet to be articulated find ways to achieve a second-best situation. These ideas will help get musicians and the live music industry back to work, but there isn’t a substitute for experiencing something special in concert next to friends you know and strangers you don’t.

One concern that will affect how quickly we get back to that place is legal liability. “The Event Safety Alliance Reopening Guide” is a 30-page document written in consultation with lawyers and promoters from across North America, and it asserts up front, “Everyone has a legal duty to behave as a reasonable person under the same or similar circumstances. Here, the key circumstance is how to reopen (a) during a highly contagious global pandemic in which (b) even asymptomatic people can carry the disease, and (c) most places currently lack widespread testing, contact tracing, or a vaccine.”

Many venues’ attorneys are going to question the wisdom of concerts by McCready and Rebillet at a time when state officials still struggle to contain the Coronavirus and prevent its spread. If someone became ill and died after the McCready concert, it’s easy to imagine a grieving family bringing a lawsuit. Temple Live may feel emboldened by the nobility of its fight for freedom, but there’s a good chance that larger concert promoters will be more circumspect.

Updated at 12:56 p.m.

The Travis McCready show took place in Ft. Smith, Arkansas on Monday night. Here’s a report from The New York Times.

Updated at 2:10 p.m.

Consequence of Sound has photos from inside Temple Live of the show and the socially distanced seating configuration.

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.