Tav Falco and The Music at Hand

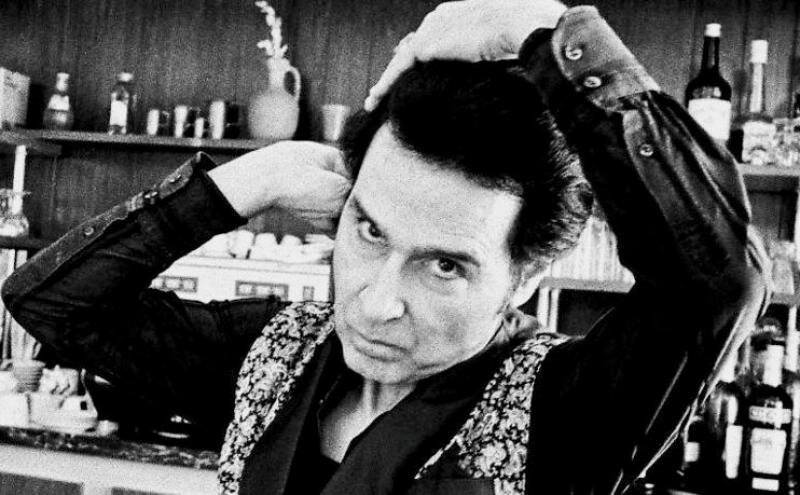

The founder of Panther Burns talks about art, music, Memphis, Vienna, war and more.

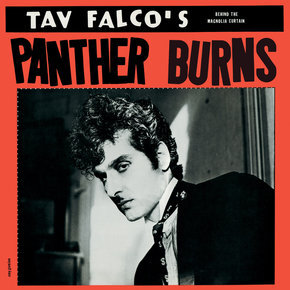

Yesterday's essay on Tav Falco's art began as an introduction to this interview, then developed a life of its own. Falco plays the Ogden Museum of Southern Art's Taylor Library tonight with the band that put him on the international map, Panther Burns. On the band's recently reissued debut album, Behind the Magnolia Curtain, Panther Burns reduce rockabilly, country and the blues to core impulses - less deconstruction than destruction of everything but the most necessary parts.

The band would never be that radical again, but even as the players became more conventional in their orientation, there remained a weird, wild hair at the heart of Panther Burns. Falco discusses the common thread in his art including his photos, which are part of a show that opens Saturday at the Ogden as a part of Art for Art's Sake. His answers, as you'll soon discover, are not what you'd expect and exactly what you'd hope for.

How are you?

I’m holding up. We’re doing some work on our apartment today, and it’s very dusty in here. My voice is a little scratchy.

You’re in Vienna?

Yes, I’m in the theater district of Vienna. I moved here, I made a transition from Paris after four years in Paris in 2004, to Vienna.

Why Europe?

When Bush came into office, we went in the front door, I went out the back. That’s part of it. Then, there’s cultural reasons. I came to Europe with Panther Burns, a group that has opened many doors for me. My one and only group. I came here in the ‘80s for our first tour, and we landed in Amsterdam. I saw these bicycles and people living in large houses with many apartments, and I thought, “Well, this is quaint and intriguing. How can these people live this way?” I could never do that. So much different than the shack I’ve lived in in Big Hampton and Memphis, in the working class district of Memphis.

After a tour of Europe, I began to see a little deeper into the culture here. I began to see how the fabric of life is predicated on life and culture and music. It’s a part of every day existence. It’s something that people need to feel complete, so Paris and Vienna embrace international art and music. Here, you have the best music, the best art, the best museums, theater, and all the best music from America comes through here. Culturally, we’re not deprived, although I did feel, in retrospect, sometimes, a little deprived in Arkansas and Memphis and even in New York. Culturally, on a certain level. Although, absolutely, America has culture. There’s no doubt, but it’s something that is special and that has to be dug up and cultivated for the most part. Of course, we have a heritage in Memphis. We have some painters and we have some artists. New Orleans, has a musical culture, there’s no doubt about it. One of the cities in the United States, one of the cities that I think that in most respects cultivates its musical heritage.

But America is a very, very new country by comparison. In Europe, I’m in touch with long traditions. Centuries of music and art. I’m not on the rock n’ roll scene here. Vienna is not a rock n’ roll town, and Paris isn’t either, so much. Although in the ‘60s, people like Vince Taylor had rock ‘n’ roll bands in France that were very much appreciated and very much a part of the environment there. In fact, my French guitarist, started in the band Vince Taylor at age 17. What I’m trying to say is I feel like I’m in a cultural Camelot here. I’m in touch in a much easier way, in a more sensible way. I started Panther Burns in a fit of frustration, trying to be a filmmaker and photographer. There was no real forum for me. I did have a showing in 1977 in video art at the Delgado Museum, but those kinds of things were rare. Of course, it’s good for the artist to be lean and hungry. Keeps him in a sanitary frame of mind. A lot of good things happened in Memphis, a lot of ground was broken. A lot of emotional and artistic credit here, and to some degree in New York, and New Orleans. Europe took up slack at a certain point in my development. I could either go back to Memphis and be a rocker and a provisional artist, or I could forge a new career in Europe. I chose the latter, because it was an unknown.

I’ve always taken the path that was full of unknowns and risks, and challenging. There was language here. French, Italian, German, I studied them all. I’ve gotten a handle on them. Spanish. I found it very rewarding. I would like to continue my life in Europe. We play in other parts of the world. Australia, all over Europe, Russia. It’s exciting. For some people, for certain kinds of Americans, it’s rewarding, an adventure. I think that Orson Welles approached Europe in much the way that I have. I watched this interview that Pier Paulo Pasolini, the film director, filmed on Orson Welles during that 12 years that he lived in exile in Italy trying to get his movie produced and finished. I’m not sure that he ever quite finished it, but there’s a version floating around. Welles had to fight every inch of the way to get his films made. He had his own vision, his own personal vision. That’s what we do in Panther Burns. Marketing’s one thing, but artistic vision is what it’s all about. We try to make traditional decisions where possible, but it’s absolutely the vision of Panther Burns that matters.

When you started Panther Burns, what did you want it to be?

It was a musical and theatrical realization of this vision of the panther that was entrapped in Panther Burn Plantation outside of Greenville, Mississippi. It was a metaphor, and we took this name and we tried to embody this legend within the music of the Panther Burns. All of the important dances and the important jazz, the important music that we know as American music came upriver from the South, came up river from New Orleans, into Memphis, and into New York and Harlem. This is the music that Panther Burns represents.

The legend of the panther: when they were clearing land for cultivation in Mississippi around the Panther Burn plantation, the animals were dispossessed from their natural habitat. They cleared the land for larger cultivation of cotton. Large brush piles were created, and some months later, the farmers came back and set fire to these brush piles. The animals who once lived in the forest were living in these brush piles. They perished. There was one panther, however. It had no place to live anymore. It had nothing left except to harass the planters and the farmers, to raid their chicken coops and howl all night. He became such a nuisance. They formed posses to track him down, but the farmers missed with their rifles. They set traps, but the panther eluded the traps. He was cunning. One night, they tracked the panther into a canebrake of wild cane growing. They set the canebrake on fire, and the place became known from that thereafter as Panther Burns. This is what I envision Panther Burns to be. The embodiment of this metaphor in a poetic sense.

You express this through rockabilly, blues, Southern music?

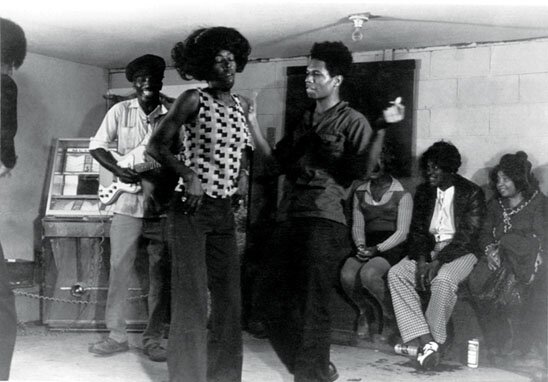

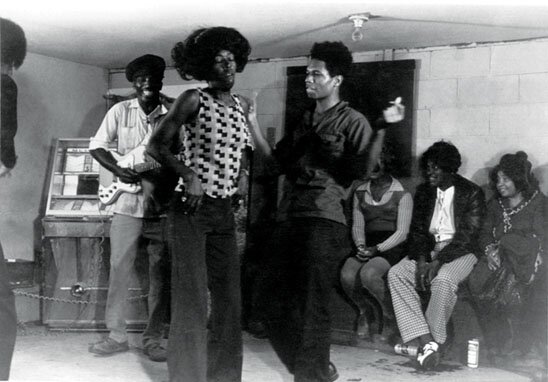

Well, this is the music at hand. This is what artists do; they work with their materials. When I met Alex Chilton, who was a rock ‘n’ roll player, when I destroyed a guitar at the Orpheum Theater on the occasion of the so-called ‘Last Waltz’ performance of 1979 [by Memphis’ Mud Boy and the Neutrons], I was only listening to country blues on the one hand, avant-garde music like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Eric Dolphy. So the idea of playing rock ‘n’ roll was foreign to me, I hadn’t listened to it since the psychedelic era. I lost interest in the ‘70s. The idea was to dig up esoteric songs in this body of music. Now it’s introduced me to rock ‘n’ roll. We were playing Memphis music, rock ‘n’ roll, rockabilly. We played on the first show four blues, country blues, three rockabilly numbers and one tango by Xavier Cugat.

With this music, the lyrics don’t mean much even though there’s some poetry in blues music and country blues. A lot of it is music tied to the earth, music of everyday life. Music of brother against brother, betrayal, lost causes, betrayed love, unrequited love. This is the music that we felt close to. We felt we could interpret. We felt like voodoo was connected to the dark waters of the unconscious. That’s what our music is about. This is how we reach audiences, we cast a spell. We’re always striving, reaching for an aesthetic, searching for that aesthetic. Reinvent that aesthetic without losing it. This is what’s been challenging, and this is what has kept that interest up over time, over the 33 years of the Panther Burns.

I’m working on a new film, it’s not a Panther Burns film, and there’s no Panther Burns music in it, but I was working in photography and film before I started the band - out of frustration, as many rock ‘n’ roll bands get started. It’s like what Charlie Parker said, the job of the art is to break down the barriers. To break down barriers between the arts. Part of the job the Panther Burns is that. Performance art, video art, so-called fine art, poster art, this sort of thing. - I didn’t see a lot of separation. The aesthetic, in a sense, runs through all of my work.

How do we see that in your photography?

In this exhibition, the “50 Photographs: An Iconography of Chance,” it’s essentially the long vision of that panther in Mississippi. It’s those moments of time, and those times when the creature knows that it’s a personal vision. He’s looking at what’s around him in a way that nobody else can see. Perhaps it’s the idea of the robust American individual, but it’s a personal vision. It’s a vision of that cat, who finally was alone. Not particularly an alienated vision, but it is a sequestered vision. It’s a vision that is personal. It is a vision that is, to a certain degree, of torture. There’s the third degree of looking at what’s around you and seeing that which is haunted, that which has been vacated. That which has been abandoned. This is what my photographs represent.

Those photographs present a moment looked upon by an individual, by an artist. A moment chosen for its qualities. In my view, the quality of an abandoned scene, a scene that is haunted, that has been walked away from. That still is inhabited by spirits and ghosts beneath the surface of the photograph, or behind the facade of the buildings. Behind the veranda of the country estate, and all the stories, and all the histories that must have gone before in that structure. This is what a photograph can bring out. This is what my pictures illustrate.

This same exhibition was shown in Mallorca in 2009 by the Juan Miro Fondacion. In Mallorca, my short films were shown the day before the photography exhibition opened. And there was a band concert, same as what’s happening at the Ogden. A foundation in Mallorca contacted me, and it was their initiative to put all of this together. No one had ever approached me about collecting all of my work together in one event, and I think people assume the connection between the short films, between the music of the Panther Burns, and between that of the photographs. The photographs are an everyday existence, just like the blues comes from everyday life, and the poetry of tango comes from the poetry of everyday life. There’s parallels between the blues and tango.

It seems like you’re careful in your photos to avoid drama or telling too much.

Yes, these pictures, the content is something that’s walked away from. The moments speak for themselves. There is no need to infuse them with any kind of heightened reality. When you see them in their entirety as a series, they take on a different impact. When you see them individually, it’s just shots. You begin to sense the persona when you see them altogether. What I’m trying to say is the content and the persona of the photographer cannot be separated. A “photographer” photographer, can be separated, but if you’re an artist, it can’t be.

They’re deadpan images. There’s nothing that can be added to them or subtracted. They speak for themselves because it’s the nature of the photographic medium as I have used it, which is straight photography. There’s no enhancement to these pictures. There’s no cropping. They’re straight-edge black and white prints from the original negative. There’s a level of honesty about them. In some of my pictures there’s a sense of irony. That’s not the overriding factor.

Memphis clearly helped shape your creative imagination.

Certainly, I lived in Memphis for 17 years, and at a formative time in my development. In my book Ghosts Behind the Sun, I have come to terms with Memphis - its history, its background, as I perceive it. That book has been a way for me to come to terms with my existence, and all of the emotions that I lived through there, and the knowledge that I gained there. What I am today, I’m a product of Memphis. But now, I’m an American living in Europe. I can’t live in the United States, either, now because I am uncomfortable living in a country that is waging unnecessary war. It’s become very disturbing and morally compromising for me. My parents live in Arkansas, where I grew up. I would like to be with them more frequently, but I can’t go back. Not the way America is destroying the lives of other people. It’s profoundly disturbing.

Related Stories:

Alex Rawls