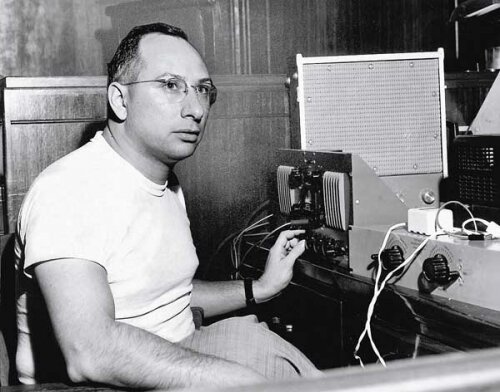

Remembering Cosimo Matassa

Producer and engineer Craig Schumacher remembers the man behind the board during the heyday of New Orleans R&B--a day before there were boards.

Tuesday, Cosimo Matassa was buried. As sad as his passing is, it’s reassuring to know that he lived long enough to know how loved and appreciated he was. It’s hard to say that any death is a relief, but it was tough in his last years to watch someone who was as outgoing and friendly as he was silenced by the stroke he experienced in 2009. He seemed almost instantly to become a smaller man, and one hard to reconcile with the robust person who sat down with me before a panel we were doing together at the producers and engineers’ PotLuck Conference in 2008.

For 20 minutes, he told me tall tales and corny jokes, only half-answering questions about his role in the recordings made in his studio preferring instead to wisecrack. I don’t remember any of the stories because he wasn’t telling history’s backstage stories; they were about him and his friends saying and doing crazy things. His friends just happened to be ridiculously talented people who made life-changing music.

After he died September 11, a friend from Toronto emailed to tell me about the time in the ‘90s when he came to town, went to Matassa’s grocery, and asked if Cos was around. It’s hard to imagine that this approach would work with many legends, but a few moments later, Matassa came downstairs and they talked on the sidewalk for 15 or so minutes. He told shaggy dog stories and answered questions his way before signing an autograph and going back inside.

Matassa wasn’t allergic to talking about what he did, though on paper and as he described it, it wasn’t much. He wasn’t riding faders or tweaking an air hockey table’s worth of knobs the way producers do today. Arranger Dave Bartholomew did much of what we think of as a producer’s role today, by working out the sound of the songs, and he would describe himself as the guy who hit the “start” button. But artists routinely credited the same good-natured quality that I encountered for creating a great vibe to create in, and when gearhead engineers at PotLuck asked about what I assumed to be the the mics and equipment of the day, he answered them directly with the same enthusiasm he brought to everything else.

He was also game for as long as he could be. When the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame put a commemorative marker on the laudromat that was once home to J&M Studios, Matassa sat in folding chairs with Bartholomew on North Rampart Street for the ceremony, and he went to Cleveland when the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame honored Bartholomew and Fats Domino in 2010. Only his family knows how he felt about attending these events (if anybody did), but I prefer to think of those moments as the expressions he could manage of his generous spirit.

Craig Schumacher produces Calexico and Neko Case among others, and he met Matassa when in 2004 he and producer brought TapeOpCon—the producer and engineer conference that became PotLuck—to New Orleans. He remembers Matassa:

Cosimo was one of the greatest engineers in the world. His legacy is only now being realized as he was not one for shameless self-promotion. He was a journeyman and a tradesman who approached recording with the goal of always capturing the best of the artists he worked with. In 2004, we were fortunate enough to have him as our keynote at TapeOpCon, and he would often repeat the saying that "a lot of really talented people made me look good" as a way of deflecting attention from himself. But he was their equal as his talent was being in the moment with the musician and getting the job done time after time.

He helped define the New Orleans sound more than anyone probably realized at the time by capturing the performance of all the players he worked with by letting them be themselves. He recognized true talent, and he loved music but did not get hung up on the little things. When asked where the pick axe sound came from for "Working in a Coal Mine,” he said they just went with what was handiest and quickest, and that was a mic stand being hit with a metal rod.

He placed so little importance on being part of so many of American music history’s greatest moments that when you look at his body of work, you feel ashamed as an engineer for not knowing more about the man and his studios. I consider myself very fortunate to have spent time with Cosimo and heard the stories like getting “Tutti Frutti” done right before the three-hour session was coming to an end, and how up until that moment the producers were not letting Richard play the piano. He said that someone suggested that Richard should play the piano on the last take, and from the opening downbeat everyone knew something special was happening. He was vague when pressed on who made that suggestion—and someday we may find out who it was—but it won't surprise me if it was Cosimo.

He was simply one of the greatest engineers of the 20th century and his legacy will survive long past many of today's named "producers" as his recordings were infused with his character and soul and that undeniable J&M, crazy-below-sea level groove that made American music made in New Orleans distinctive and exciting.

Other valuable remembrances of Matassa

The Times-Picayune

Al Jazeera America

Gambit

New Orleans Advocate

WWL

New York Times

Video of an interview with Matassa from Nola.com