John Broven Compiles More Than He Writes New Orleans' Musical History

In the revised "Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans," the writer gives his interviews a good home.

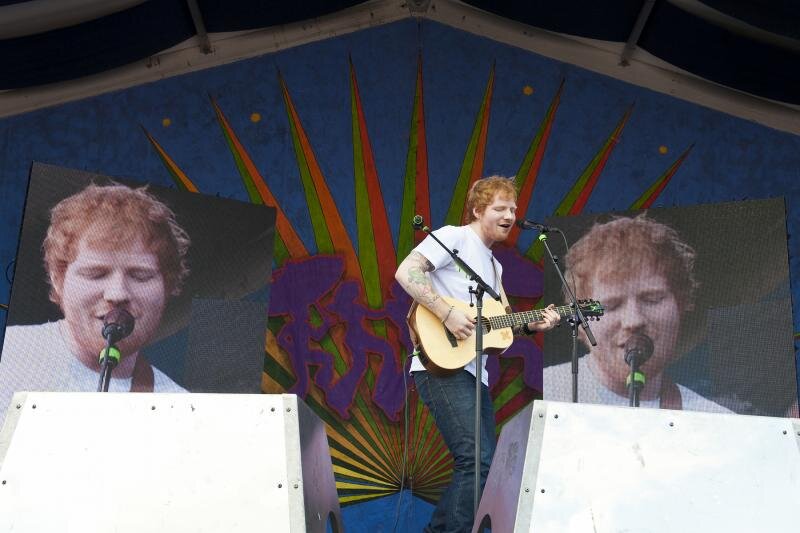

Writer John Swenson has argued that the change many feel in Jazz Fest has more to do with the passing of the generation of artists who defined the festival than the artists who replaced them. Earl King, Eddie Bo, Snooks Eaglin, Ernie K-Doe and Allen Toussaint were all links to the heyday of New Orleans R&B, and without those tangible roots and the distinctly New Orleanian eccentricity each possessed, the festival can’t help but seem more conventional. This year, Dr. John and Irma Thomas are the only artists from that generation to have their own sets, while The Dixie Cups joined Wanda Rouzan to perform Friday in the Blues Tent, and Clarence “Frogman” Henry, Al “Carnival Time” Johnson, and Robert Parker will perform backed by the Bobby Cure Band Sunday at 11:20 a.m. on the Gentilly Stage.

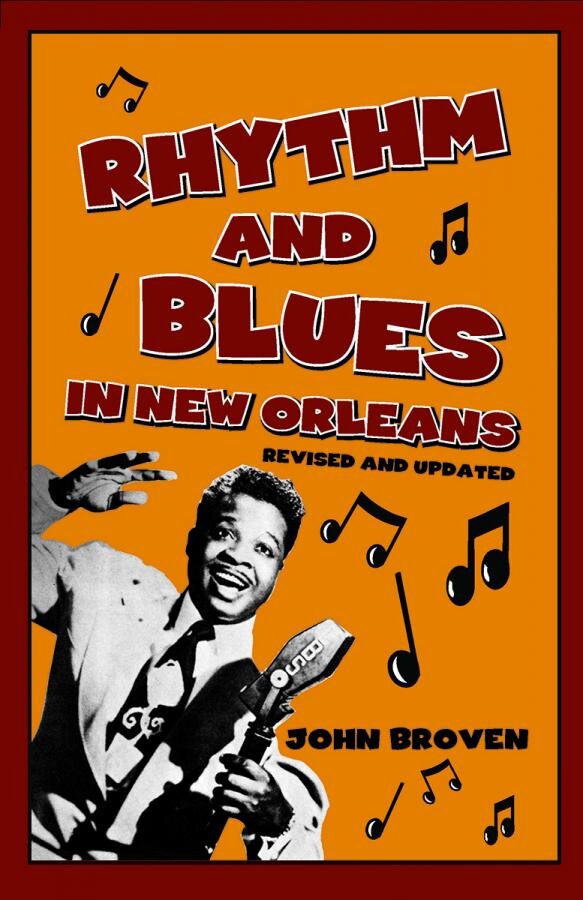

Despite its influence on the development of rock ’n’ roll, there are surprisingly few books written about that generation. Rick Coleman’s Fats Domino biography Blue Monday, John Wirt’s Huey "Piano" Smith and the Rocking Pneumonia Blues, The Neville Brothers’ The Brothers, Dr. John’s Under the Hoodoo Moon and Harold Batiste’s Unfinished Blues spring to mind, but each looks at a piece of the story. For a long time, the heavy lifting of telling a bigger story fell to Jason Berry, Jonathan Foose and Tad Jones, who wrote Up From the Cradle of Jazz, Jeff Hannusch, who wrote I Hear You Knockin’ and The Soul of New Orleans, and John Broven, who blazed the trail with his Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, which was first published in 1978.

Last year, Pelican Publishing put out Broven’s revised and updated version, which includes interviews Broven conducted after the book’s initial release, as well as new material that emerged from interviews with Tad Jones, Jeff Hannusch, Rick Coleman, Ben Sandmel, and The Ponderosa Stomp’s Ira Padnos.

Even in its third edition, Broven’s Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans is more of a filing cabinet than a book. He approached writing the book not as a man with a story to tell or a perspective to explore but a collection of interviews to house. He did the legwork to meet and talk to the people who made the music, and he wrote a book to store the things that they said. In liner note prose, he provided frameworks for the musicians to talk about their worlds and the music they made, and let them say what they want. When Art Neville claimed everybody in The Hawkettes wrote “Mardi Gras Mambo,” Broven deferred to him, even though Jody Levens cut the first version 1953 in Cosimo Matassas’ studio a year before The Hawkettes’ release.

Broven’s affection for the music and the musicians is clear throughout, so while some quotes give us eyewitnesses to rock ’n’ roll history as it was being made, others simply capture the musicians’ excitement for what they and their peers were doing. Today, ome of those lines read like default mode statements that we’ve seen from other musicians, but almost 40 years ago, they were fresher, and taken as a whole they paint a picture of a united music community—a reassuring vision for any fan of the music.

I suspect record collectors will find Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans more satisfying as information is organized not by narrative but by chronological periods and inside of those, by labels, venues, and other relevant umbrella topics. Those more accustomed to processing music information by where someone played or released his or her music would find that more logical than those who want or expect a clearer narrative.

Still, Broven’s book is one of the few existing histories of the music, and it belongs in the collections of most fans of New Orleans music, at least as a reference guide. And since every year seems to take from us another performer he interviewed, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans is one of the handful of places where the people who made the music speak for themselves.