P.J. Morton Comes Home to Start a New Label

The R&B singer and Maroon 5 keyboard player returns to his native New Orleans East with a new mixtape and big plans.

[Updated] PJ Morton spent much of this past spring letting people know he’s back in New Orleans. The R&B singer has been part of the Cash Money family and is the son of Bishop Paul S. Morton, leader of the Greater St. Stephen Mass Choir, but musically he’s best known as the keyboard player and backing vocalist for Maroon 5. That gig took him to Los Angeles where he has lived for the last six years, but Morton moved back to New Orleans in late 2015, and he plans to make the city the home base for his new venture, Morton Records.

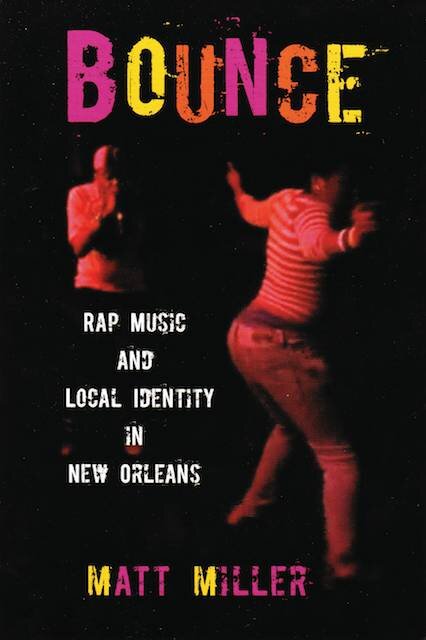

Morton reintroduced himself to New Orleans with a free mixtape, Bounce and Soul, Vol. 1, and in a cheeky bit of synergy, gave away free physical copies of the CD in PJ’s Coffee shops. He’s joined on it by DJ Raj Smoove, Juvenile, Trombone Shorty, Lil Wayne, Mack Maine, and 5th Ward Weebie among others, and 5th Ward Weebie also appears in the video Morton shot for “I Need Your Love,” one of the songs given a bounce remake for the mixtape. His return has been so measured that it borders on viral. He played a show at The Howlin’ Wolf, a Jazz Fest night show with Christian Scott, and on Saturday he’ll perform not at the Superdome but at the Convention Center, the site of the Essence Empowerment Seminars. He’ll perform a free show at 4 p.m. with an expanded band that includes special guests DJ Raj Smoove, Dee-1 and 5th Ward Weebie. Those aren’t the sorts of events that make big splashes, but they’re more in keeping with what Morton is trying to do.

“I’m one of those guys, I never planned on moving back,” he says. “I love home for my family and to eat my mother’s cooking, but growing up here, I felt suffocated in a way. I wasn’t a jazz musician, and I couldn’t sign to No Limit. I wasn’t a rapper. With the aspirations I had for pop music and R&B music, I had to leave. The reason I left is related to the reason I came back. Now that I’ve had some success, I want to bring some infrastructure so that some people don’t have to leave the way that I had to leave.”

Morton is personable. Guys who join well-known bands often are because nobody successful needs to take on a difficult personality. Over coffee, he laughs easily but takes conversation seriously. At the mixtape listening party at PJ’s Coffee’s Bywater warehouse, he schmoozed effortlessly and made anyone who talked to him feel like they connected. He has an everyguy quality, which explains how he can move effectively through different professional worlds. His songs are impeccably musical, but sometimes it’s hard to know Morton through his songs. Ironically, Bounce and Soul, Vol. 1 puts him in sharper focus, even though he has already released versions of the songs before. The mixtape is clearly the work of someone who loves bounce and New Orleans hip-hop, and the snappier percussion throughout leads Morton to nimbler, less deliberate vocals.

At the same time, he’s someone who also knows how to stay in his lane. Morton never assumes that he shares the rappers’ gifts, nor does he pretend to be an underground guy. His instincts are those of someone who reaches for broad audiences, which was more likely part of his appeal to Maroon 5 than a result of his time in the group. His pop/soul chops helped get Stevie Wonder to the party, but little on Bounce and Soul, Vol. 1 will confer underground cred on any but the most bookish listeners. On the other hand, he clearly hears the possible commercial applications of beats associated with bounce.

When Morton first left town in the early 2000s to live in Atlanta, he didn’t see a musical future in New Orleans. Although it’s a music city, it’s one that didn’t know what to do with someone who didn’t play jazz, funk, or hip-hop--many would argue it still doesn't. As a pop/R&B guy, Morton didn’t see a path forward, nor was there the sort of infrastructure to help musicians find their way to the marketplace. The city’s mentality didn’t help.

“Play here five times a week, so people don’t value you,” he says. “Kermit will play here and you can get in for $10, then he goes to New York and they’re paying $50 and $100 to see him.”

When Maroon 5 played Jazz Fest, Morton started to reconsider New Orleans. Being there with Maroon 5’s entourage instead of local friends, he found it easier to see all the talent and things there were to love and not fixate on the things that drove him crazy. “I think that’s when the seed was planted. I think I want to be back home and shine some light on it.”

When Morton joined Maroon 5, the band rehearsed regularly and sometimes spontaneously. He had to be nearby and available when duty called, but the band’s success and singer Adam Levine’s role on The Voice have forced schedules to be more rigorous and projected out farther in advance. When the show is taping, Morton knows that he’s at liberty. The Internet has also made it easier for him to be farther from Los Angeles. He can be at meetings from remote locations if necessary, and he can also participate in the music business from two time zones away. And that is the goal. Morton’s not trying to run New Orleans or be a big fish here.

“What I love about New Orleans is, they don’t really care what’s going on in the rest of the world,” he says. “That’s why I think it should be packaged and shipped out. I want to get this sound and get this talent and make it here, but it’s all about exporting for me. But it’s about this being the epicenter for the creativity to happen.”

Since Morton’s father is a minister, PJ's journey started in a spiritual place, and he began writing gospel music. Because of his background, it’s tempting to hear spiritual thoughts coded into his songs, but Morton says that’s reading more into his songs than he intended. “I think soul music in its very essence always has a spiritual connect to it, but I’m never explicitly giving a message like that,” he says. “My message is definitely more based around love. That is God to me. Love is our religion.”

The gospel industry assumed that he’d go its way, and early on he had a gospel duo with his sister. That wasn’t in his heart though. “I felt a fraud trying to be an R&B Christian artist,” Morton says. The songs he wrote were love songs, so he tacked on “God” to put a Christian fig leaf on them. His career would have been simpler if he had gone down that path. He certainly would have started making money sooner. Churches wanted him and his sister to sing to their youth ministries, and some of those churches paid very well. In that world, fees are agreed upon up front and don’t fluctuate based on your draw or how much booze you sell. But Morton passed. “I didn’t run from something. It just wasn’t something I was called to do.”

When Morton talks about this subject, the word “calling” comes up a few times, and it’s clear that he remains fluent in the language of Christian faith. He still gets offers to perform at churches and considers them in a way he once would not have. In 2009, he wrote the book, Why Can't I Sing About Love?, so if churches ask today, the odds are good that they actually want him and not simply Bishop Morton’s son. If asked, he can do a G-rated show. “I didn’t leave angry, so I didn’t have to rebel,” he says. “A lot of these R&B cats when they’re mad at the church, they try to use as much profanity as possible and as many naked girls as possible. I never went to that extreme because I wasn’t running.”

Morton understands why people might be tempted to hear Christian thoughts in his music. “That’s in me,” he says. Growing up in church affected his notions of drama, of theatrics, of performance, and of passion. “My father taught me when I was singing early as a kid, You’ve got to put a little cry in your voice,” he says. “You’ve got to make people feel what you’re saying. These are lessons he taught me when I was seven or eight.”

He didn’t learn about music from old jazz guys; he learned from singers in the choir and players in the church. He never learned to read music, so he considers his ability miraculous. “My father prayed over my hands when I was a child,” he says.

Morton came to the same realization that other R&B singers with similar backgrounds did. “My shows start to feel like church because of what’s in me,” Morton says. “I think that’s no different from Aretha Franklin or Sam Cooke. That’s not what I’m singing about, but that’s the spirit it comes from. Because it’s the same soul.”

Morton grew up in New Orleans East. His father’s church was there, his family lived there, so it’s appropriate that Morton is building his studio on the lot where his father taught him to drive. He hopes to one day be able to do some kind of festival in New Orleans East as well, but for now he’s just trying to get his business up and running. The studio won’t be one he hopes to rent out though. Instead, Morton envisions it as his work space for his own music and as a place to write and produce for others. “I want to get my friends who are musicians to come to New Orleans to record their records and show them this special place,” he says.

“I should be more concerned about starting a record label right now than starting a studio,” he jokes. His degree from Morehouse College is in marketing, and he sees the financial future of Morton Records being tied to connections with brands and tapping into the marketing budgets and reach that they can provide. It’s not a willy-nilly thing. He thinks the key is to find the right connections, and Morton is putting that theory to the test by partnering with McDonald’s to play their booth Friday.

“Coca-Cola and T-Mobile spend a hundred million dollars on marketing”—only a small fraction of which is needed to make a record and put it out, Morton says—“so if you find the right artist who’d be right for that brand, then it saves the label from spending that money. I think it’s the future.”

He is also bringing a lesson to Morton Records that he learned while in the Young Money Cash Money family. At a time when many the sound of the boardroom can be heard on many albums as decisions are made to cover bases and reach markets, he wants to trust artists. “Make some music you actually believe in instead of chasing hits,” Morton says. “They let artists be artists. No chasing. Leading. That’s more risky, but when you win, you win.”

Morton Records’ first release is Bounce and Soul, Vol. 1, and he deliberately kept it light. He didn’t want to overwork it or overthink it. “I can make some very serious music,” he says, so while he and his family were staying at his mom’s house, he set up a mini-studio and started playing around. Morton enjoyed hearing bounce on the radio and realized that it was something he’d never tried. Once he started chopping up beats, he liked what he was getting. When his business partner Ezra “Izzo” Landry suggested they see if Juvenile would be up for laying down a guest spot, Morton asked. He said yes, as did Mannie Fresh and other guests, and the ease with which the project came together made him optimistic. “I think we’ve got something,” he thought. “But I was just messing around.”

He conceived of the mixtape as a gift to the city, so the guests just made it a better gift. When he played a mixtape release show at The Howlin’ Wolf, the guests were all there including Dee-1, Trombone Shorty and Mannie Fresh, who dropped by on his way to his own gig.

“It felt like love,” Morton says. “I wanted some kind of confirmation that I was in the right place—that i was supposed to be home—and that seemed like it. It was almost like, We’re happy you’re home. Whatever you want to do, let’s do it.”

Updated July 6, 1:12 p.m.

The "Sticking to My Guns" video was added to the post.