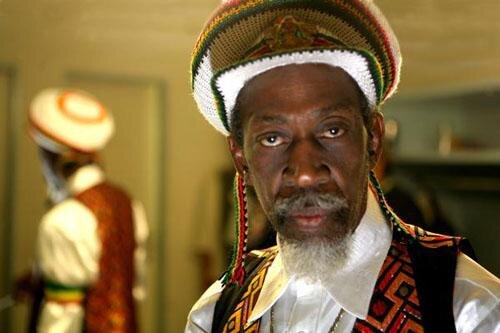

Last Night: Bunny Wailer is Still Here

The last surviving Wailer was all about endurance Tuesday at Tipitina's.

[Friend of My Spilt Milk and publisher of Louisiana Cultural Vistas Brian Boyles recently attended Bunny Wailer's show at Tipitina's and interviewed the reggae icon as well. Here's his report.]

Bunny Wailer, last surviving member of the group that brought reggae to audiences around the globe, is alive and well and performing music. He lives on a planet where marijuana is ubiquitous and increasingly legal; his own role in that movement is deep and ongoing.

“The high grade, it is the most significant and symbolic substance in all existence,” he says, sitting in a tour bus outside Tipitina’s, where he and a crack band performed nearly two hours of roots reggae. The set included “Legalize It,” the anthem written by his former band mate, Peter Tosh.

“I’m satisfied because Peter searched, fight hard, and we have his son here”—he motions toward the front of the bus—“who is doing approximately what his dad did.” The freeing up of weed and the lines of succession in reggae’s royal families were prevalent themes in our conversation, in which we were joined by his extremely astute wife and Ayo Scott, the New Orleans visual artist. The music performed this evening by Jah B, as he’s known, expressed these themes eloquently.

The performance included his solo material and heavy doses from the Wailers catalog. The classic “Blackheart Man” came early in the set, establishing the tone and tempo for the night—thick, bright roots reggae. Wailer's vocal tenor was succinct but playful, willing to scat, and supported at times by additional reverb and effects. The current band features members of the jazz reggae group Zap-Pow, including guitarist Dwight Pinkney, a veteran Studio One session player who recorded with the Wailers. Bunny knew Pinkney prior to their musical careers.

“We can talk about those old days, and things that took place, and how we have survived,” he says in the tour bus, “and about the brothers have not survived, but they’ve left a legacy.”

The band is an expression of that legacy. Three younger men make up the horn section, which sounded subtle but tight, as did the two back up singers. No song goes too long, but what songs they are. We get the Wailers’ “I Gotta Keep on Moving”, “Easy Skanking”, “Walk the Proud Land”, “Is This Love”, and “No Woman No Cry.” Wailer's rendition of “Trenchtown Rock” is just…what need one say? What is it to see this man—Bob Marley’s vocal comrade since boyhood--move spritely across the stage, dipped in flawless white silk fatigues and all the red, gold, and green ornaments of a rasta general, under that portrait of Professor Longhair, adorned this Jazzfest season with an Indian headdress? In the wake of several departures from the rarified class of actual musical geniuses, the experience of hearing these songs from one of the three voices that made reggae the first “world music” is, well, it is good medicine.

When the set ended, Scott and I were welcomed to the back of the tour bus. I asked Wailer if longevity and vitality ran in his family.

“My family name is Livingston,” said the man born Neville O’Riley Livingston. “You feel me, Living-ston. It’s a longevity thing. I show the kids. The things they see me do, that make me the popular person that I am, that they, too, would want to be sure that they, too, would be popular.

“I’m still here as a surviving Wailer, and I’m focusing on putting on the kind of show that we see tonight.”

What does it look like, from his perch as a founding father, to see the endurance of reggae’s popularity throughout the world?

“When we came to England for Catch a Fire [The Wailers' 1971 release] to play, to sign to Island [Records] to play, the world was not turned on to reggae as yet. But from then, on to now, I’m seeing that the family is getting bigger and bigger.” He laughs.

“The culture of Rastafari, I-and-I as Rastafarians, what it brought to the world--the music, yes, but”--here, in the bus, Bunny Wailer breaks into the Rastaman Chant—“hear the words of the rastaman, yeahhh. Babylon your throne gone down. That is the culture we brought with Catch a Fire. But the symbol of our struggle was Rastaman and it still is.”

Scott mentions that he visited the village of Nine Mile, birthplace of Bunny and of Bob Marley and home to the Bob Marley Mausoleum. I ask about marijuana legalization in Jamaica. Bunny points to the incalculable role the Wailers played in raising the profile of the herb.

“Ganja is us. If you wanna talk about ganja, you gonna talk about Wailers.” His wife calls it a struggle against 100 years of prohibition.

“Me father used to sell herb, what they called ‘donkey weed,’” says Wailer. “And a rastaman said, no, this, and he showed him the high grade.”

“And right now, I came here and some brothers gave me some herb, some dressings, and I mean, I’ve never seen herb like that.” He cackles with glee. “Fabulous man, some science!” We all laugh at the idea that there is weed that Bunny Wailer hasn’t seen.

Wailer's wife observes the interesting “recycling” of family members into the reggae tradition, the involvement of a new generation in their fathers’ music. The sons of the Abyssinians, of Third World, of Tosh are joining new outfits, but also the backing bands of Bunny and other older statesmen. Ayo’s daugher is two months old, my son is two years old. How, I ask, do you nurture a child who expresses an early love of music?

“Make sure him have all the instruments, all the things he can play and be creative with—make sure he has that. Don’t let it come to him when it’s too late.”

I say that I try not to take the instrument away, even when it is played loudly and, often, first thing in the morning.

“That’s the way he wants to play them! Leave him.” That night, I pull the Casio keyboard back out of the closet so that it will be there when my son comes home from a trip up north with his mother.

Did Wailer listen to Fats Domino when he was growing up?

“Yeah, mon, all the time. We used to dance to it. The man was wicked hot.”

We thank them both for letting us talk with them, and for coming to New Orleans. His wife jokes that next year, Bunny turns “three score and ten.”

“Next year is seventy,” he says with a grin. “Seventy. I’m still doing what I’m capable of. I’m still doing it.

“I’m still here.”