James Brown - "A Really Big Ocean"

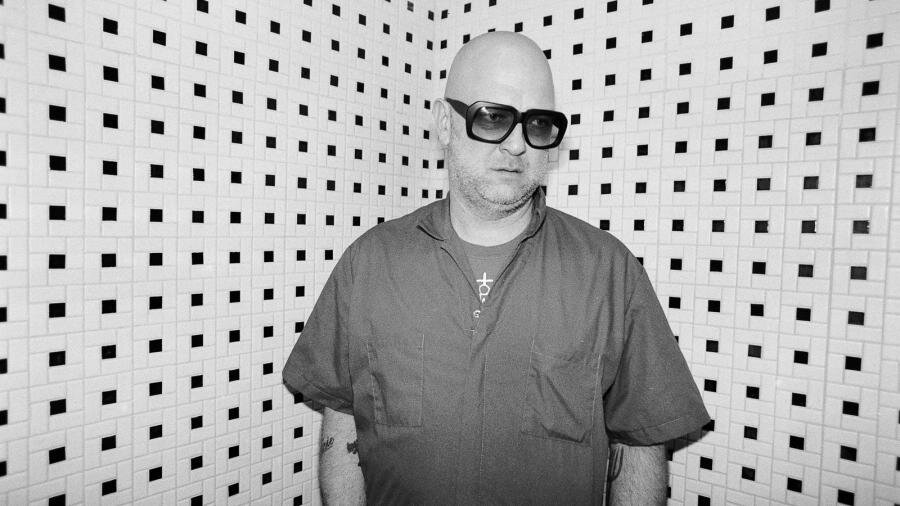

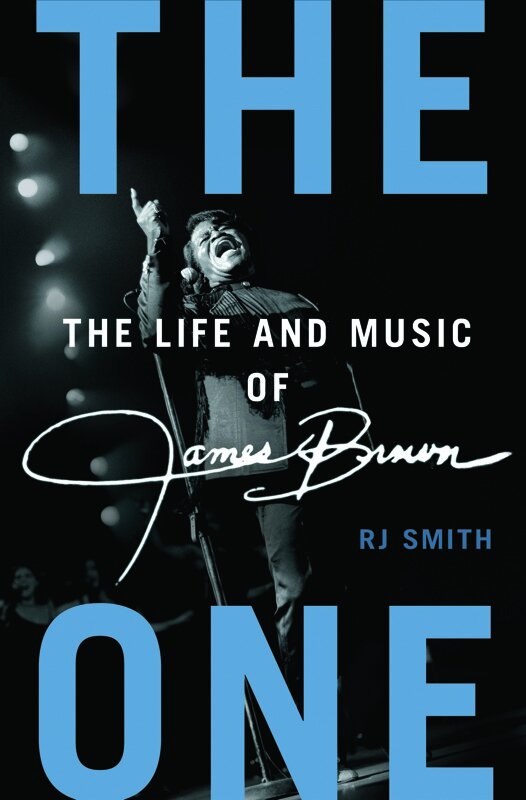

R.J. Smith discusses James Brown before appearing at Octavia Books Tuesday at 6 p.m. to sign copies of his Brown bio, "The One."

Writer R.J. Smith talks about James Brown and "The One: The Life and Music of James Brown."

Writer R.J. Smith has spent the last four to five years with James Brown. Brown's music has been a part of Smith's life for as long as he can remember, but the long-time music journalist has spent his recent years writing The One: The Life and Music of James Brown - the definitive biography of the Godfather of Soul. It has been likened to Peter Guralnick's epic chronicling of Elvis Presley's life story in Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love, but it's hard to imagine two volumes on Brown because he was such a difficult person. Smith carefully and smartly reveals Brown's flaws without reveling in the Backstage Confidential stories. He also balances Brown's flaws with his assessment of his musical accomplishments, but I wonder if that balance could be maintained as perfectly if the story stretched out over another book. Or, would the tawdry, ill-advised and cruel stories start to overshadow Brown's greatness? As is, Smith illuminates how monumentally important Brown's Live at the Apollo was, the mythic elements built into his stage shtick known as "The Cape Act," and the breakthrough embodied by "Cold Sweat," and much, much more while never oversimplifying an obviously complicated, often infuriating man.

Smith will be at Octavia Books this evening at 6 p.m. to discuss Brown and sign copies of The One.

By the time you'd finished writing, how did you feel about James Brown?

I (sigh) - how do say this - I felt really bad for him. I felt like he was a really sad person in some ways whose behavior and impulses I recognized in my own [behavior] and of people I've known. I don't think he was a particularly happy fellow in his last years. The biggest problem I had throughout the book and especially at the end was trying to understand how someone who made this tremendous music and art could be violent and reprehensible in his private life.

I'd imagine that at some point it would take some of the fun out of the project to have to keep chronicling his shitty behavior.

One thing that saved me from feeling that was that a lot of his shitty behavior caused him in the eyed of some folks late in his life to be something less than human. He was a cartoon and a joke, compared to a shoe in Kenneth Cole billboards and the butt of jokes on Saturday Night Live and late night talk shows. Even when talking about the worst of his behavior, I tried to find the person there and tried to understand that this wasn't a monster but a person who behaved monstrously. I wanted to understand the motivations that shaped some of that behavior. I was trying to not hate the guy because I don't. I wanted to show that he was a person and not a thing.

What was your relationship to him and his music before you started the book?

I always had the feeling of him being incredibly vast and interesting - the way that he popped out of the '50s and reimagined vocal group traditions, then in the '60s was at the forefront of soul, then in '70s, no one person invented funk but if you had to lay it at one person's doorstep, you'd probably have to lay it at James Brown's. Someone who did such amazing things in three different decades, then in the '80s was reinvented through hip-hop. I thought, "Here is a really big ocean to swim around in," and I knew it would never be boring.

Did you ever meet him?

I never did. I'd seen him perform, but I'd never sat down and talked to him. I wish I had. I guess I wish I had. [pause] Yeah, I wish I had, although it would have been hard to write this book if he were still around because he wouldn't have liked me talking to some of the people I talked to.

The last time I saw him was in the '80s and he had worked the Entertainment Tonight theme into his set. How do you account for his extreme swings in taste?

There was a certain streak in him that was always there that was a streak of perversity and wild weirdness. If you talked to him about it, I think he would say it was good show business and that it got people talking about him, but things like the first hit he had repeated the same word over and over. Or that hair, which people think about when they think about James Brown. In the '50s, he wanted to be a macho guy who wanted desperately to be known as a ladies man, but he wanted it on his terms. When he decided he liked something, he was going for it, whatever you thought of it.

That sort of mixed bag was an issue throughout his career. At that same show, he took over on organ for what felt like 10 minutes when he was likely the fourth-best organ player on the stage. I wondered if those moments, the ET theme and other moments in shaky artistic taste represented some sort of triangulation between his ego, his business sense, and a guess at what it is the kids like these days.

He could never easily answer the part about what the kids like. He wanted the kids to like him, and he listened to what was popular at any given moment from country to pop to hip-hop, but while he wanted to fit in with that audience of the moment, he also had this feeling, "I'm the best. Michael Jackson's doing me. Prince is my student."

You treat him to some extent as a mythic figure in your writing. Why adopt that voice?

Because he is one. He came out of nowhere in the literal sense - in the woods, a place that doesn't even exist anymore. He's the guy who had to take care of himself. He had to educate himself and fight for himself and raise himself. His parents were somewhat around, but they weren't good role models and they weren't around reliably. He's that Booker T. Washington figure. He's also so vast as an artist. As a dancer, he was incredible. As a talker, he was amazing. There aren't that many people like him that I can think of.

What was James Brown's great accomplishment?

Maybe staying alive. Not disappearing. Not disappearing as a kid who was taking care of himself on the streets of Augusta. Not disappearing when he was sent to prison as a teenager. Not disappearing in the Jim Crow South when he was good with his fists. When he was in his early 20s, he drove his car into this white guy's tractor. He was so mad about that he knocked the farmer off his tractor and was sent to jail. That could have been incredibly calamitous. God was looking out for this guy in all kinds of ways.

Beyond that, his ability to connect with audiences is what made him amazing. I don't think anybody ever understood better what a fan base or what a crowd in front of him wanted better than James Brown. He could read an audience, read their minds. He knew what was on their faces when he was singing. He knew what the next song should be based on how well this one was going over. He knew what his dance moves were going to make the audience feel or say. He really knew how to read a crowd better than anybody.

To what extent did his early incarceration shape him?

The first time he went to prison as a teenager who came out in his early 20s, it shaped him in startling ways. It gave him a sense of discipline that he was looking for and craved and really appreciated. I wouldn't recommend that experience to anyone, but it gave him a structure to his days, and it provided him a father figure - the guy who ran the youth system in Georgia at the time, who by several accounts was looking out for James Brown. It gave him a sense of order that he didn't have as a kid in Augusta.

Beyond that, it was a place where he learned a lot about music. He had a radio that he listened to in prison. He was in a gospel group in prison. The first prison he was in had a tuberculosis ward, so he was singing to tuberculosis patients. He really learned a lot about how to affect an audience with song by singing to tuberculosis patients in prison.

You wrote that he was only able to relate to women sexually. Can you expound about that?

The truth is a little more complicated than this, but he felt abandoned by his mother. That was always the way he explained his relationship to her, that she disappeared and came back into his life decades later. He could never stand the feeling of anyone leaving him, whether it was a drummer or a woman in his life. He was always going to be the person who kept those around him on a leash, dependent on him. He would lavish women with gifts and pay for everything and really want to have this child-like dependency on him. At the first signal that they were looking at someone else or that they didn't appreciate what he had given them or that they were thinking about leaving him - bad things always happened at that point.

I don't know that he had "healthy" relations with anybody in his life. I think power and dependency were touchstones of his friendships and his relationships with the musicians, his relationships with women, and his relationships with his parents. He wanted to put his parents on the payroll and make him dependent on him.

It's an oddly lonely book, despite how many people pass through it. Was there anybody he had genuine relationships with?

I think the best relationships he had were with people he needed too, people he couldn't dominate, like Syd Nathan, that he had to fight with just to get a record out. Or Ben Bart, the manager who taught him a lot early on. Folks that were almost father figures, he would argue with and go to war with, but he knew he was learning from them.

When writing about "Cold Sweat," you said the song "is about an enduring, dominant present." What did you mean by that?

That's an early moment in funk history that we can look at as important in terms of the evolution of that music, and it seems to me that in terms of how basic it is chord-wise and progression-wise, and how the beat isn't confined to a measure - it's expansive and loops around and repeats itself as many times as he wants it to repeat, it's about the experience of now and feeling good in the moment. Making due with what you've got now, and having everybody play an expression of the rhythm that's in the room all together at the same time.

I think it's interesting that time is felt in music through chord changes, and that if there aren't chord changes or melodic changes, one moment sounds pretty much like the moment that came a minute before or comes a minute later.

That's right, which can be boring if it's done the wrong way. So many songs tell stories, and the chord structures are set up to build an emotional plotline, almost. "Cold Sweat" and so much funk doesn't do that. Those lyrics don't really tell a story. Very rarely do James Brown lyrics tell a story or get you from A to B to C. It's so much about him shouting out things that are in his head at the moment that are very deep and say a lot.

Are there critics who helped shaped your thinking about James Brown and his music?

All the writing and thinking and work of Greg Tate has always shaped a lot of what I think about music, and it has been incredibly important to me as I worked on this. And there's a writer who passed away a few years ago named David Mills - he became a TV writer who worked on The Wire for a while and Treme, and he might have even died in New Orleans [he did] - he wrote a lot about funk for a while, and he had a fascinating, open mind to new ideas and contradictory ideas. I learned a lot from him too.

Is there a period of Brown's work that's underappreciated?

We know the hits from the early '70s, the funk in the Bootsy [Collins] era and the immediate years after that under the name of the band, the JBs - we know that stuff and it's been reused as the foundation of so many great hip-hop records, but I don't think it's possible to say too much about that period of Brown's career and music. If I'd had another six months, that's the part of the book that I'd have written about more and expanded a lot more. That band was so good, they didn't coast. Every time they played something, it was interesting.

Did Jonathan Lethem's account of being in the studio with Brown ["Being James Brown" in Rolling Stone] sound accurate to you based on your research?

Definitely. He captured a lot of sides of a man that a lot of writers hadn't captured.

I walked away from that piece feeling incredibly sad. It's really rare to have a writer capture so vividly a senior musician playing out the end of his life so obliviously. When the story's over, you have the sense that the session will never come out and the band knows it, and 20 or so people are all in the business of humoring James Brown in his old age.

There are so many great things about that piece. On the one hand, he captures a lot of what makes James Brown in all eras great - a lot of the flavor of his personality and the vibe of being in a room with him. And the magazine gave Lethem the length to be not difficult but sophisticated and complicated. He painted a very complicated emotional dynamic. It's one of the very best pieces I've read of what it can be like to be in a studio, to be there as music is being made. This is music that probably isn't very good and the musicians are not excited about, but you feel what it's like to be in this room with really talented people trying to make sense of a song and trying to make it work.