King James and the Special Men are Singles Again

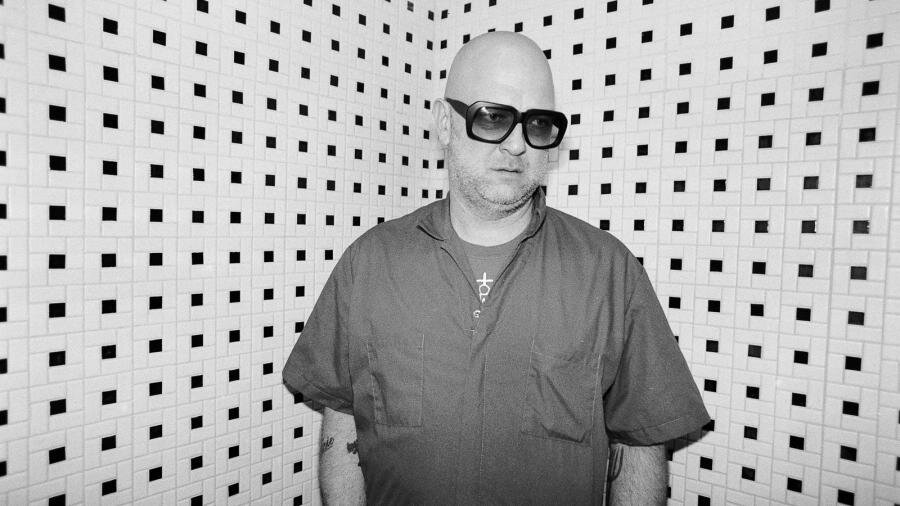

Special Man Industries' singles releases aren't only a marketing device; they're an aesthetic and a window into Jimmy Horn's creative process.

[Updated] “‘Eh La Bas’ is one of the oldest songs in the New Orleans repertoire,” Jimmy Horn told Talia Schlanger on WXPN’s “World Cafe” recently. “You’ve got recordings and recordings and recordings of it going back to the beginning of recording history. It’s a New Orleans song, but it’s a Creole song. That’s Haitian Creole. That’s the islands. New Orleans and Haiti and the Caribbean at large are very much connected, culturally speaking. Leyla [McCalla] is one more amazingly talented neighbor that I had access to, and I asked her, Hey, would you be interested in doing a version of ‘Hey La Bas,’ taking it all the way back to Haitian culture, doing a new New Orleans thing?’ We’re not trying to recreate the past or reinvent our traditions. We’re trying to make new art with the traditional palate.”

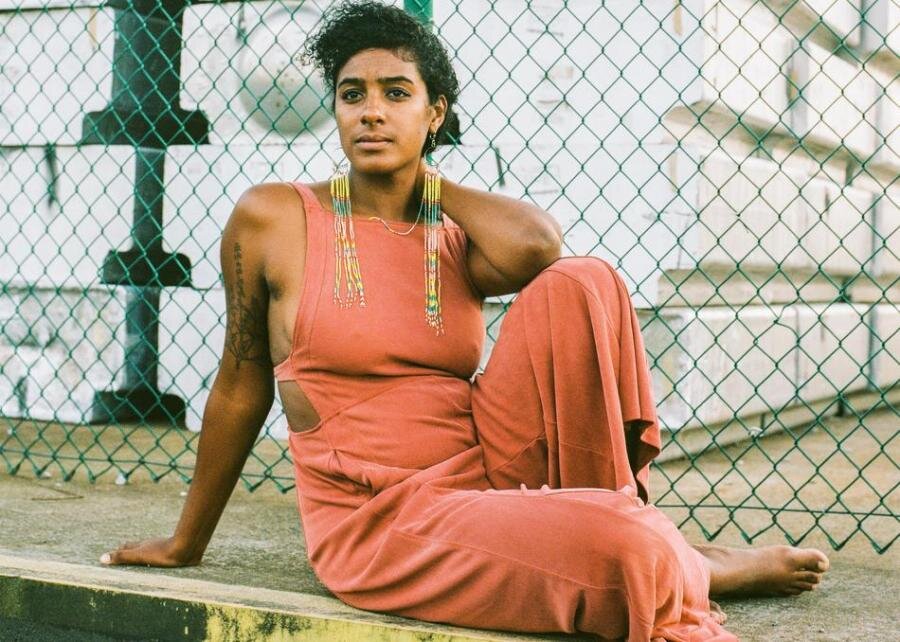

Horn spoke to Schlanger about his relationship to New Orleans’ roots music as part of a show featuring his band, King James and the Special Men. The band performed live at the Saturn Bar with guest appearances by Hurray for the Riff Ralf’s Alynda Segarra and Leyla McCalla. Segarra sang the lead vocal on the soul ballad “Don’t Tell Me That it’s Over,” the first 45 Horn released on his Special Man Industries label.

“It’s rare that I sing someone else’s song, but there are those moments where you hear a song and you feel this pain or, Wow, I wish I wrote this. I feel this so much,” Segarra told My Spilt Milk before Jazz Fest. “That was one of those moments for me. It’s just such a classic song. It’s one of those very tight, perfect storytelling songs, and when I recorded it with him, I was obviously thinking about Irma Thomas. To me, Irma Thomas, and the recordings that she has made are the epitome of the perfect break up song or, just like heartbreak on tape. And I really wanted to live my Irma Thomas fantasy and go there.”

Horn has been doing his “new New Orleans thing” as King James and the Special Men for nine years now, and he has become of the outlaw flag bearers for traditional New Orleans musical culture. He has yet to be booked to play Jazz Fest and has yet to experience mainstream recognition in New Orleans, but his Monday night gig—first at BJ’s Lounge, now the Saturn Bar in the Bywater—has become mandatory for those who want a taste of the R&B that made New Orleans famous. And King James plays it straight, ballads and all. Many band revisiting traditional forms tweak them for modern times, often picking up the tempos or adding contemporary pop or rock touches. Maybe they’ll add an undercurrent of irony to distance themselves from the plaintive, naked emotion in the songs that inspired them, but not Horn. He drills in on a single thought or emotion, shedding any hint of Dylanesque impressionism in favor of classic clarity. Some changes are inevitable because the musicians in The Special Men and any band playing traditional music today grew up in a world that included music by The Beatles, Michael Jackson and Miles Davis. They grew up with different music than the guys who recorded in J&M Studios, so they have different ideas about what sounds musically logical. Still, King James and The Special Men stay as true to their influences as they can manage.

Horn’s story is a familiar one in New Orleans. Person comes from another city to visit, falls in love with New Orleans, stays. Horn started in Utah then Seattle, and like many musicians including Segarra and McCalla, he began the New Orleans chapter of his life as a busker. He has become a prickly defender of New Orleans traditional culture on social media because, like so many people who have moved to the city, he didn’t grow up with its magic and treasures it in a that’s hard for those who have never known life without it. Horn also has a bare-knuckles sense of humor that can easily be misunderstood as combative. Still, people who have worked with him found his intensity and no-nonsense attitude helpful. According Alynda Segarra, “Jimmy is a larger than life character. He is a visionary, and he sees a lot of brilliance and magic in the artists of New Orleans.

“I really loved working with him because when he’s with an artist in a studio, I really felt so cared for by him and I felt so supported. He does what any great producer does, which is push you to be ‘you.’ He doesn’t want you to be anybody else. He wants you to get out of your way and let the music come through. I really respect him and feel so lucky that I was to work with him.”

Leyla McCalla enjoyed the experience of recording “Eh La Bas” with Horn so much that she asked him to produce The Capitalist Blues, her 2019 album. She expanded her musical palate for the album from stringed instruments in small configurations and was backed The Special Men. That change gave her music a greater sense of community, but that didn’t come at the expense of the intimacy that is central to her art.

“Jimmy has musical instincts like a shark,” McCalla says. “He hears the potential in a song and he digs into creating that with grit, tenacity and soul. He is never without opinion about what direction to move and that sort of directness really helped me to thing big about my songs. I will carry that for rest of my life.”

Despite those testimonials, King James and the Special Men has largely been a live phenomenon. They had only released one six-song LP, Act Like You Know, before June 2018 when Horn announced plans to release a series of singles on his Special Man Industries label. “Don’t Tell Me That It’s Over” and “Eh La Bas” were two of the first three releases, along with “Ti Fi,” which features Louis Michot of the Lost Bayou Ramblers. Since Horn announced the series, he reconsidered it and decided to leave it open-ended and change the way he thought about it.

“It’s a different business model,” Horn says. “I’m not concerned with albums. This is a singles-based label. It’s an idea that progressed.”

The decision to make 45s his preferred medium makes sense on a number of levels. He can record two songs more cheaply than he can record 10, which means he doesn’t have to take gigs he doesn’t want to play to pay for his musical ambitions. King James and the Special Men model themselves on the heyday of New Orleans’ R&B, and the truest expression of the music of that era came via singles. Albums were marketing decisions made by labels, whereas singles came from artists who cut them when they had songs. Horn also found that—simply—he really enjoyed making singles.

“I loved it,” he said after recording with Segarra. “This is really gratifying to me as an artist. It’s something I took to right away and I wanted to do more of it.”

He’s not dogmatically opposed to albums and has some longer songs that will make more sense on an album, but he understands that sometimes albums are the best way to present the music. “If somebody came to me with Electric Ladyland, I’d say, Okay, that needs to be a double album, it needs a gatefold package with all kinds of artwork,” Horn says. “But if they brought me one of Hendrix’s other records, I’d say a song at a time.”

Historically, singles outsold albums. Before The Beatles, Bob Dylan, The Beach Boys, and The Rolling Stones ushered in the album era, singles were the primary medium for music. The flood of landmark albums and the attention paid to them by the emerging crop of music journalists in the ‘60s shifted attention to albums, so much so that it’s easy to think that they became the dominant mode for pop and rock music. Albums expanded the possibilities for musicians who were starting to think of themselves as artists and not simply entertainers, but the market for singles remained larger than the one for albums. In 1974 for instance, Barbara Streisand’s sentimental theme song to the movie The Way We Were outsold Bob Dylan’s Planet Waves and John Lennon’s Walls and Bridges combined. It sold two million copies, but Planet Waves only sold 600,000 units sold that year despite four weeks at number one on Billboard’s album chart. Walls and Bridges only spent one week at number one in the U.S., but two hit singles—“Whatever Gets You Through the Night” and “#9 Dream”—couldn’t get it past 500,000 copies sold. All three records were certified gold, but gold records commemorate more than a million dollars in sales, not the number of copies sold. Since singles cost approximately 75 cents at the time versus four dollars or so for albums, singles had to sell more than four times as many copies as albums earn the same RIAA recognition.

Horn questions the place that albums occupy in our musical culture in typically direct terms. “When’s the last time you got an album stuck in your head?” he asks.

The logic of focusing on singles makes financial sense as well. “If you sell a thousand 45s out of your trunk, it’s basically the same as the money you get from a million Spotify plays,” Horn says. “That’s good math.” He points to such famous labels as Atlantic and Studio One, where attitudes toward releases used to be less precious. If one release stiffed, the labels put another one. Despite all that, the album continues to hold a special place in the imaginations of musicians, even in the streaming era when playlists and individual songs are the more relevant units of measure. The album’s grip is so strong that Horn had to rationalize his choice to the Special Men.

“This is the way I explain it to my band,” Horn says. “If they don’t like one song, why are they going to buy 12?”

Thinking about the business of singles got Horn thinking about the songs themselves as bespoke products. He wrote “Don’t Tell Me That it’s Over” with Segarra in mind, and he loved thinking about her persona, and her voice, and the options that they presented him that his own voice didn’t. “I’m a bawdy, loudmouth, Good-Time Charlie kind of singer,” he says, and hearing Segarra work on one song made him wonder what happens when each song is treated as a stand-alone piece, not only in terms of how it was made but how it was heard. Singles don’t have album sides to give them contexts or fastball side openers to build up some momentum to help them engage listeners. They work or they don’t, which is a very Jimmy Horn, no nonsense way of thinking about them.

The idea of treating each song as individual extended to his production of McCalla’s The Capitalist Blues, which is very much an album as the songs deal with the way working class people live in a culture and landscape so completely shaped by money and its interests. Even though it covers a lot of ground musically, it’s sonically unified even though Horn says that he and McCalla used a different lineup for every song, adding musicians to the core band to make sure each piece gets the instrumentation it needs.

“We didn’t make anything -ish,” he says.

The process helped him appreciate his musical life in New Orleans, even though it hasn’t taken him to the venues typically associated with the city’s traditions. That’s not a point he harps on, but Horn’s conversation makes clear that he’s aware of the inroads he hasn’t made into the city’s consciousness. Part of the “new New Orleans” idea that he mentioned on “World Cafe” is the desire to have a career on his own terms with his own definitions of success. As he says, Horn’s not reinventing anything musically, but the context for King James and the Special Men is different. Like cratedigger soul bands Sharon Jones and the Dap-Kings, Charles Bradley, Durand Jones and the Indications, and Nicole Willis and the Soul Investigators, King James is a boutique product and he treats it as such. There are no sleight of hand efforts to make 60 years disappear, and he’s not trying to be Throwback Guy. He’s making a classic sound in 2019, and Horn knows that there’s a ceiling for how big a band that does that can be.

There’s a lot he can do before that becomes an issue though, and that knowledge is liberating. It’s easier to comfortably focus on the music once you’ve honestly faced the business side and made peace with how that will work for the foreseeable future. You can approach a career in music positively and not see it as an endless struggle to achieve benchmarks that keep moving—benchmarks that always make it look like you’re not measuring up. It’s easier to recognize success when it happens and not see every day as another small failure.

“Working with Leyla on that album, I realized I’m so rich,” he says. “Living where I live and having my little standing in the community. I can call people like Carl LeBlanc and Shannon Powell and Topsy Chapman. I can say, Hey Joe Ashlar, can you come and put some organ on this for me? More than these people who have status quo set-ups with big teams living in a city where there’s an actual infrastructure who don’t have to boil their water on a weekly basis—we still have huge advantages. It’s the culture and the place and the people who live here. And that lends itself to one song at a time. Hey, let’s do this song justice. Let’s bring in the best musicians in the world.”

That approach was consistent with the way McCalla thought of her music going into the sessions. The Capitalist Blues is an album, but “I always imagined the songs as their own little worlds,” she said in an interview earlier this spring.

Finding his medium is just one facet of Horn’s efforts to come to grips with his gig and how to make it fulfilling going forward. He now knows King James and the Special Men are not touring band playing as an opening act on the road for $500 a night. Some of the Special Men have other gigs and some have families. Some have been in touring bands and don’t want to tour anymore. That realization didn’t require as much of an adjustment for Horn as you might think because touring wasn’t one of the things that drew him to a life in music as a kid in Utah in the ‘70s. Playing was, but not touring.

“A musician—he blew fire out of his mouth, he wore platform boots, and he made records,” Horn remembers. “That’s all I knew. I’m right back there wanting to rock out, breathe fire, make records and eat cheeseburgers. For me, being an artist was a recording artist. And I grew up on 45s.”

King James and the Special Men play Monday nights at the Saturn Bar starting at 10 p.m. They’ll take the month of August off.

Updated at 2:54 p.m.

Jimmy Horn is from Utah, not Idaho, Act Like You Know is an LP, not an EP, and the band has been together nine years now. The text has been changed to reflect these corrections.