Instant Culture's Going to Get You

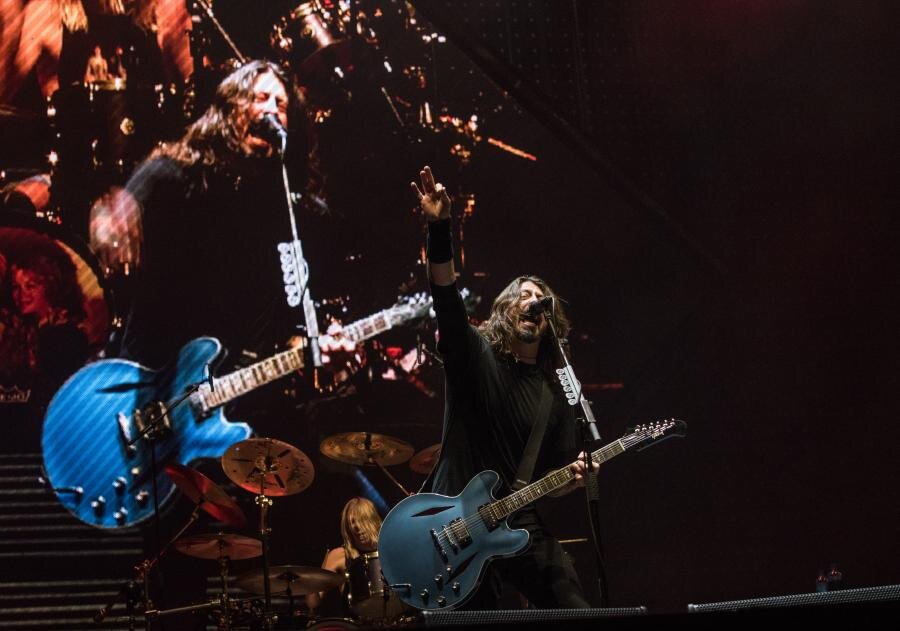

What Foo Fighters' Dave Grohl doesn't get about culture.

Since Foo Fighters' appearance at Voodoo, I've been riding Dave Grohl and Sonic Highways pretty regularly here (and here) and on Facebook--probably creating the impression that I'm more hostile to him than I actually am. He's too amiable for me to genuinely dislke, and there are people making lousier, more cynical music in the world.

But like him or not, the premise of the show and album is that the places where music is made matters, but that's not what the songs themselves suggest. As reviewer after reviewer noticed, there's no sense of place on these songs. Local flavor is reduced to phrases pulled from interviews he conducted in New Orleans, Nashville, Chicago, Seattle, and the album's other ports of call. As Stuart Berman wrote for Pitchfork, "As a promotional film for a new Foo Fighters album, however, [Sonic Highways] makes you wonder why its trailblazing subjects’ transgressive influence didn’t seep into the sound of final product."

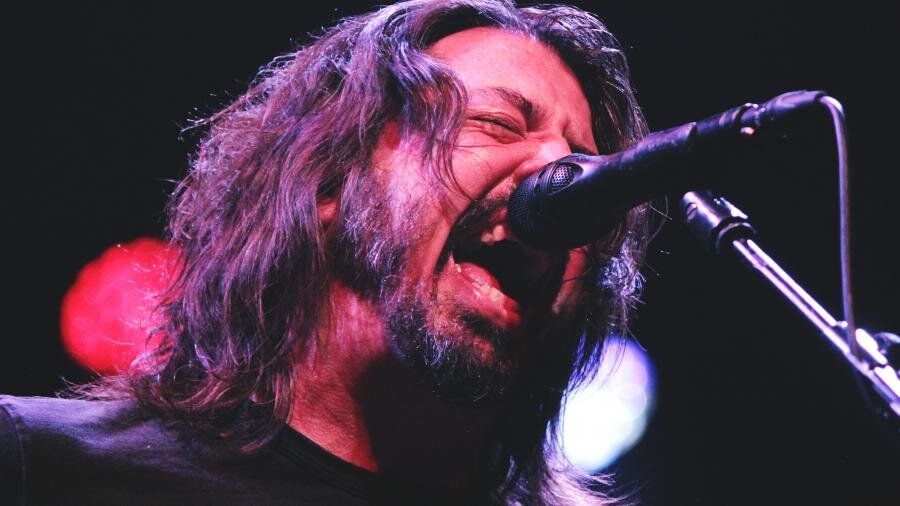

In yet another stop on Grohl's "Get Respect" Media Tour 2014, he stopped at NPR, where Bob Boilen and Robin Hilton interviewed him for All Songs Considered. Grohl is engaging and likable in the interview and talks enthusiastically about showing off his Washington, D.C. to his daughter. When talking about the album and show's premise though, Grohl said:

Every environment influences everything that comes from everyone. So in some way, environment is going to influence what you do and how you do it. It could be the weather, it could be the pace, it could be the energy of a city. It could be the musical climate of a city. It could be the history of a city. There's so many factors, and that's what I think is so interesting.

When I was young and discovering a lot of this independent, underground music, you had these scenes that were kind of isolated. They were connected within this underground network of college radio shows, or fanzines or penpals. Little independent basement record labels. But for the most part, each of these places was known for something specific.

As I got older, I started thinking, "Wow, it's kind of funny that if you listen to a band from Seattle--," a lot of bands in Seattle would share a similar aesthetic. There was something about those bands that made them sound like they were from that place. I became really fascinated with it. I don't consider myself a historian or anything like that, but when you go to a city and spend a good six or seven days there, talk to all the people--not just about the music but about the culture of that city and how it's influenced everything about that place, the food, the accent, the music.

Maybe music has an accent. Like "Oh man, that sounds like Athens, Georgia. Listen to Pylon. Listen to R.E.M. That's an isolated little scene. That's weird; why didn't it happen in Boston? Well it kinda did. You had Mission of Burma." As you go around the country, you find these little communities where people would get together and it would germinate and grow into something that became a regional movement, and I think it's beautiful and amazing, and also an interesting discussion now that everything's interconnected. How do those things happen?

All of that makes sense, but as Grohl looks for deep cultural roots of musical communities, he seems to overlook the many individuals whose personalities and tastes helped make them happen. The club owners who were desperate enough to take a shot on underground bands. The campus radio program directors who got people with interesting taste on the air. The record store with tastemaking staff. The writers paying attention to the scene. Charismatic people who go to shows, and so on. That story's not as grand, nor does it invite amateur anthropology, but it likely tells a more accurate story.

It's a measure of the speed of our times though that Grohl says "spend a good six or seven days" as if that was long enough to see a field plowed, planted and harvested. That a week represents a real commitment, and that you can drop in, talk to people about weighty stuff and connect to the culture. It's a pretty glaring flaw in the concept, one that anybody who has moved to New Orleans likely recognizes. The city's bewildering beauty is seductive, but I can't imagine who got here and thought they had a handle on it in fewer than six months--only to realize six months' later that they didn't know shit when they first thought they got it.

The flip side of this though, is that if culture can't be absorbed overnight, it's likely too durable to be wiped away easily as well. If a hurricane (that found its way into Foo Fighters' song rooted in New Orleans, naturally) couldn't wash away a musical way of life, it will take more than noise and zoning regulations to do meaningful damage.