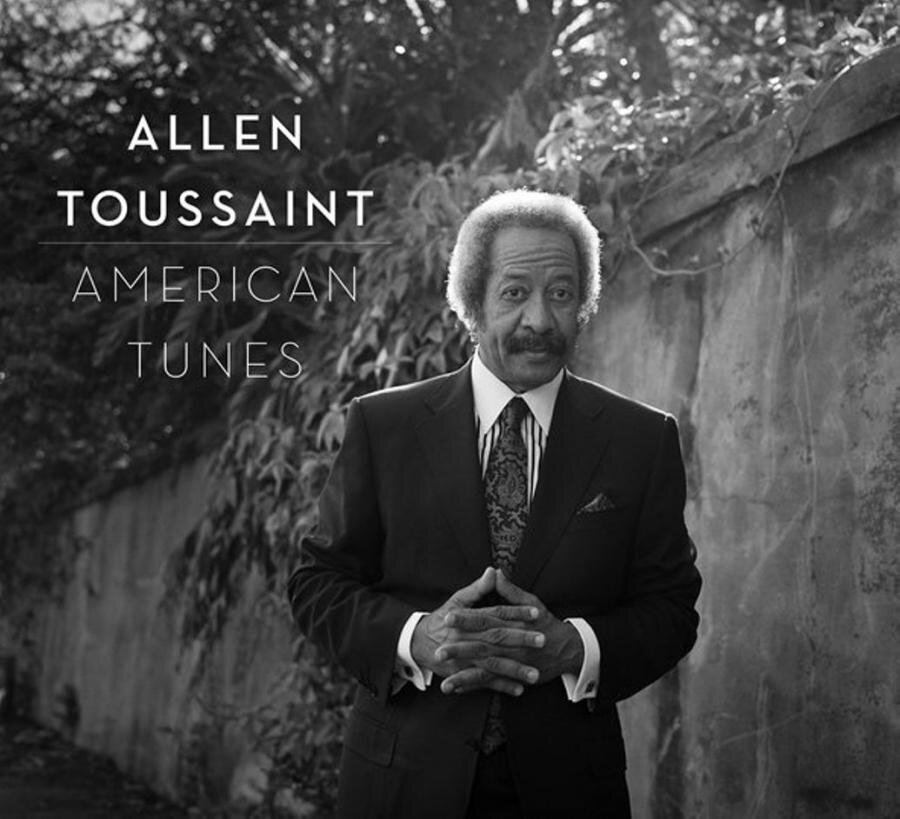

Allen Toussaint Plays His Final Songs

It's tempting to hear a final statement in "American Songs." What's really on display is something more subtle and heartening.

When Allen Toussaint’s The Bright Mississippi was released in 2009, the admiration for it came with an undercurrent of suspicion. How could Joe Henry, a musician not from New Orleans, really represent a musician so quintessentially New Orleans? And how could someone who wrote, recorded and released so much joyous music come away with something so self-consciously straight-faced?

The New York Times’ Ben Ratliff aptly likened the album to Raising Sand, the album/art project by T Bone Burnett starring Alison Krauss and Robert Plant. “This is a jazz record for people who think they don’t like jazz — as Raising Sand is a country record for people who think they don’t like country,” he wrote, but as Ratliff points out elsewhere in the review, Toussaint wasn’t strictly a jazz musician. “In fact he’s a pop musician and producer, a great one. He has nothing to apologize for. It’s just that jazz as we know it is not part of his working life.”

While Ratliff and doubters were strictly speaking right, the story had been quietly changing in Toussaint’s later years. In 2004 Toussaint told Michael Hurtt:

About a year ago I wrote several jazz songs. I call them jazz-y, because I’m not a jazz musician. I got together with my brother, who played on some of my sessions 40 years ago, to jam at the house and I turned the tape recorder on. We have about 20 things that we’ve recorded that we’re going to be releasing in the near future. Jazz is all that it’s cracked up to be, and more. It takes some doing to really be satisfying. Jazz has high standards and as far as I’m concerned, they’re well deserved.

When I interviewed Toussaint after the release of The Bright Mississippi, Toussaint sat at a piano and improvised a medley of songs we had talked about and styles we had referenced. It wasn't strictly jazz, but there was a clear sense of exploration as he approached each piece with an impeccable touch and a sense of exactly how florid a treatment each composition could bear. It was an experience I later learned I shared with Henry, who wrote in the liner notes to The Bright Mississippi:

One day in a studio in Los Angeles, while grabbing a piano overdub on a song we’d recorded earlier that afternoon, he began amusing himself between takes by blowing freely and with great invention through a song by Fats Waller. I was stunned. It was a revelation to hear this music (“my parents’ music,” he later offered) interpreted through Allen’s very unique point of view. The song, inherently rhythmic as a composition, was transfigured by a left hand schooled in New Orleans, and by the melodic sensibility of a most particular kind of songwriter. “Have you ever considered making a record like that?” I quickly asked him over the talkback. “Never,” he said with a slight grin, and kept playing by way of assuring me that he most certainly had.

In Ratliff’s review of The Bright Mississippi, he wrote, “Mr. Toussaint brings to these songs his own elegant, reserved sensibility. He doesn’t rip them apart or interrogate them on the harmonic or rhythmic terms with which they’ve usually been met; he shines them up and levels them out into slow-rolling and grandiloquent New Orleans songs, full of tremolo chords and serenity.”

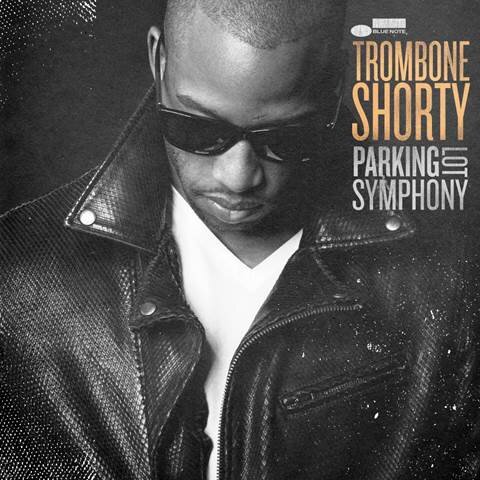

To some extent, that’s who Toussaint was late in life. It’s certainly the Toussaint that Henry describes, and Elvis Costello talks about a similar man when he tells Toussaint stories. That is the Toussaint we hear on the new and posthumous American Songs—someone with the ability to hear the rich, delicate, subtle and slyly witty possibilities that the songs chosen offered him. He interpolates Chopin into a solo piano version of “Big Chief,” and gives Fats Waller’s “Viper Drag” exactly it needs until the middle section, when he swings hard and rambles with the New Orleanian sense that there remains the door to another land hidden somewhere on the keyboard, and a player will find it if he just keeps searching. His own “Delores’ Boyfriend” has a series of witty pauses that makes everything that comes after them sound like the work of a man at play.

The Bright Mississippi’s repertoire of older songs from New Orleans invited listeners to think of the album as Toussaint revisiting his influences, but American Songs is the album that actually does that. His entree into music was Professor Longhair not Sidney Bechet, and the new album includes three Longhair covers. Toussaint’s death makes it tempting to hear the album as a final salute to his inspirations, his city and talent-wise, his musical peers, but thinking of American Songs that way misses a more basic and more human story. What I hear in these tracks is Toussaint having fun, entertaining himself more than challenging himself, and in the process exploring the full breadth of his talents as a piano player.

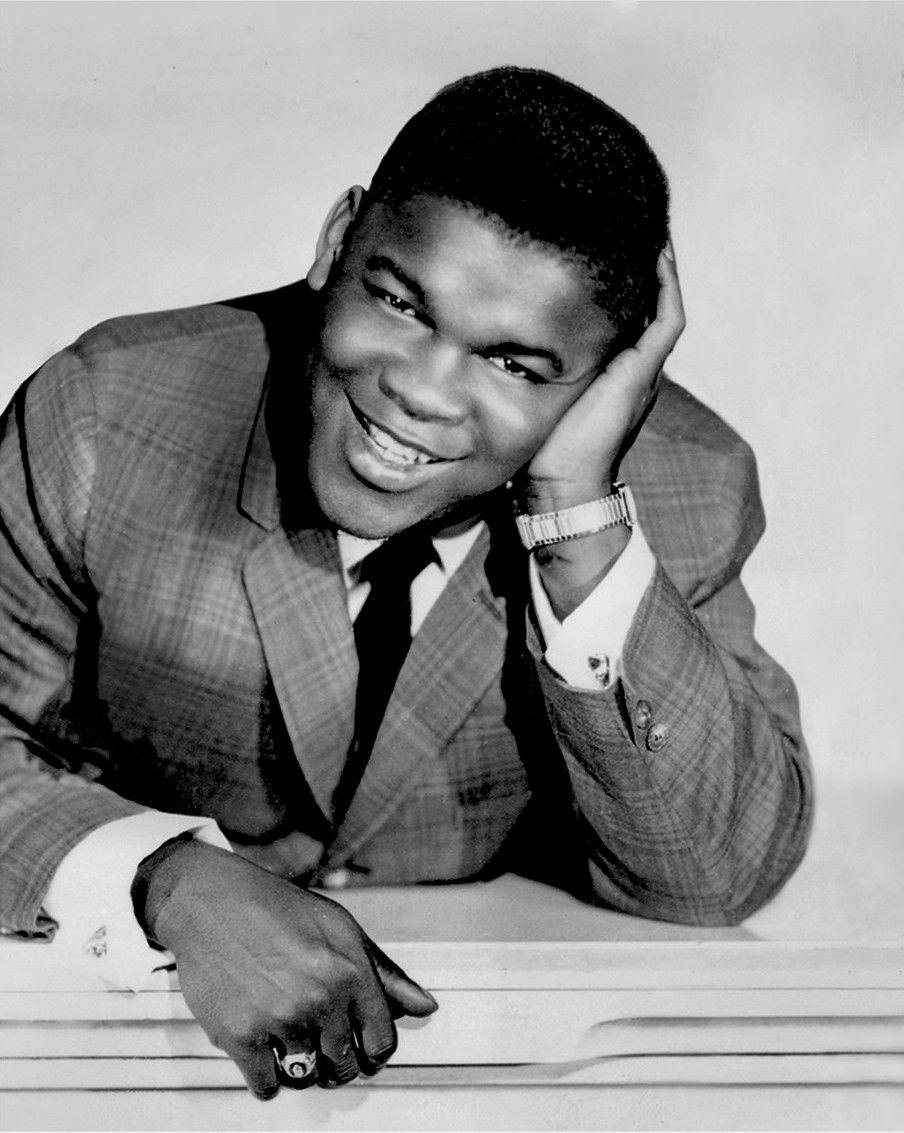

One of the Fess songs covered on American Songs is “Mardi Gras in New Orleans.” Toussaint's version is formal and treats Mardi Gras as culture. When Professor Longhair played it on Live in Chicago, the set from 1974 released this spring, he approached it as a street party. Fess wasn’t a legend that afternoon. The piano wasn’t quite in tune, but he was a working musician playing with a workmanlike band, stumbling on occasion, banging heads with his drummer at times. His “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” isn’t exactly sweaty, but like much of Live in Chicago it presents him as a man doing a job. You only occasionally hear the wild musical imagination that inspired Toussaint, but you do hear some fine moments—a hard-driving version of “Got My Mojo Working” and a version of “Mess Around” that gives you reason to believe the song was written for him. He circles back on some sour notes until they’re sweetened, and shows some of what he’s got on the instrumental “Doin’ It.”

Live in Chicago is better than simply a document, but much of its value is documentary. We live in a time when Fess’ reputation is solid, his music is accessible, and his place in history is assured. In 1974 on a radio broadcast from a blues festival, he had a half-hour, an indifferent mix, a band that was only sometimes in sync with his eccentric rhythms, and likely more reputation than fame. It’s fascinating to hear him work in a situation like this because his talent can't be hidden, but I’ll listen to Live on the Queen Mary recorded a year later with a more sympathetic band when l return to this period.