A Perfect Day?

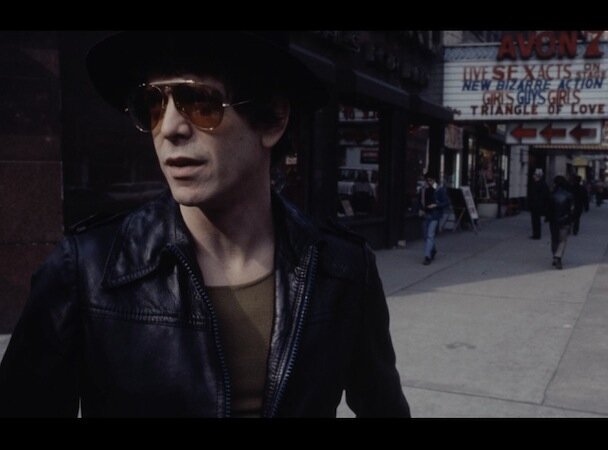

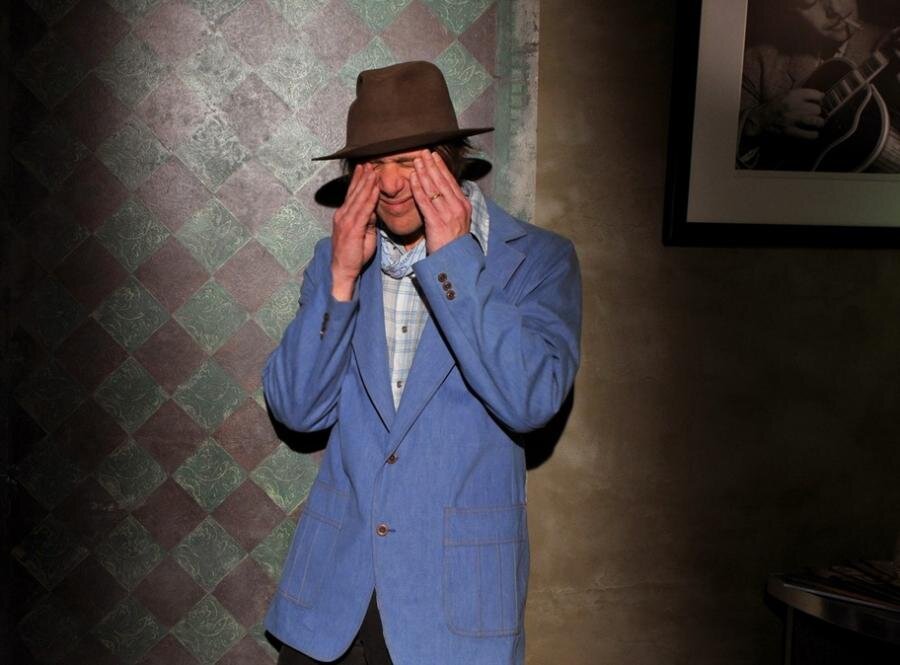

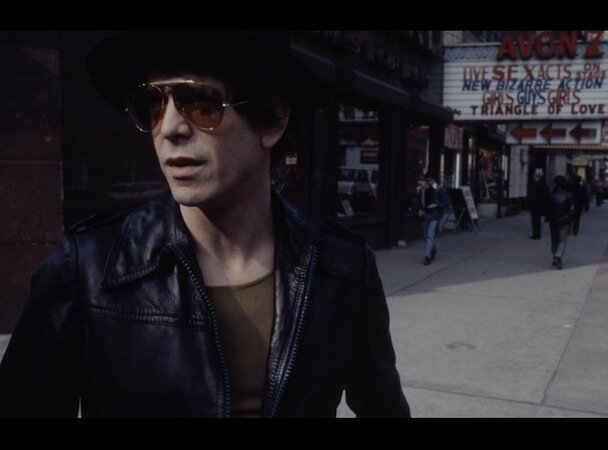

Does anybody have the nerve or chops to be Lou Reed today?

I can identify the exact moment when I stopped paying attention to Lou Reed - 2:40 into “Hello It’s Me” at the end of 1990’s Songs for Drella. The tribute to Andy Warhol performed by Reed and Velvet Underground bandmate John Cale ended with the line, “Good night Andy,” but Reed sang it “good NIGHT anDEE,” forcing it into two awkward iambic feet at odds with the sing-speak that had been his trademark throughout his years with The Velvet Underground and his solo career up to then. Fans of Reed knew that he was a student of the poet Delmore Schwartz, but little about Reed’s songwriting or performing had been self-consciously poetic to that point. If anything, his deadpan delivery treated everything like it was nothing special. Underselling the drama only strengthened it for Reed.

After 1990, he seemed to embrace his image as the street poet of New York, stepping hard on the drama to make sure nobody missed it. The detachment that the original Berlin so chilling was replaced in the 2008 Julian Schnabel concert film and accompanying live recording of Berlin by an insistent attention to every syllable of meaning. When he first recorded Berlin in 1973, he was credibly part of the story; in 2008, he made sure that there was no mistaking who wrote the songs.

I can focus with such precision on my distance for Reed because for so many years, his music was crucial to how I thought about music. His answer to marijuana and mind expansion was heroin. His version of free love was submission and domination. His “Teach Your Children” was “Kill Your Sons.” He answered Californian utopianism with chilly New York city scenes about people who could only live there and would likely die there, probably before their time. And again, his voice mattered. He sang as if he couldn’t imagine life existing outside Manhattan, so his songs were less refutations of hippie good times than an indifference to points of view outside his characters’ draggy, druggy social circles, which you had the feeling mirrored his own.

Reed routinely challenged his fans, asking them to stay with him through the aggressively noisy White Light/White Heat, the gentle Loaded, the glam Transformer, the faux-R&B Sally Can’t Dance and the oddly sentimental Coney Island Baby. He inspired critics who liked him to sooner or later dismiss him or albums. In 2000, Douglas Wolk wrote of the reissue of Rock and Roll Animal, “Reed doesn't bother to conceal his contempt for the commercial trappings he's put on his songs—‘Heroin,’ in particular, turns from savage ambivalence into an easy cartoon--and the album's hard to like now.” But the feeling was mutual, and he went after critics John Rockwell and Robert Christgau on the live album Take No Prisoners (Christgau reviewed Sally Can’t Dance, writing “Lou sure is adept at figuring out new ways to shit on people.”)

But all of that - the songs, the stance, the ambivalence and the prickliness - put something at stake time and again in his music. Over and over, he potentially put his career on the line, challenging fans to stay with him. The two discs of noise on 1975’s Metal Machine Music was a test to see who could hang disguised as art.

As time has passed, I came to return more to his Velvet Underground bandmate John Cale’s music than Reed’s, partly because Reed’s work seems so familiar to me now. Reed’s heyday (The Velvet Underground through Street Hassle? The Blue Mask? New York?) is also part of that body of culture that you should consume before you’re 25, along with Kerouac, Hunter Thompson, Lester Bangs, and Charles Bukowski. His art from that period is doesn’t mature with you. It got me and so many others out of the musically mainstream worlds and opened the door to a musical and social subculture not sung about by Rush or Kiss, at the same time implying that more were out there. But it only stays on the journey with me as a talisman because once it had ushered me (and really, rock ’n’ roll) into a new place, it had done what it had to do.

At some point, Lou Reed entered the culture, or the culture figured out how to accommodate and neutralize even him. He did an ad for a Honda scooter. He sent Christmas wishes on a Warner Brothers holiday promo CD for radio stations. Most recently, “Perfect Day” has been used to sell the new Playstation 4, and I’d like to think there’s a sly joke on gamers in the decision to use a Reed song as two dudes sing the song to each other as they move from gaming conflict to gaming conflict. I doubt it though. It's hard to imagine that anyone in the board room thought past the idea that a day spent with a pal and a new PS4 is a perfect day. It’s hard for me to watch that commercial and not think of Lou smirking from beyond the grave.

Holly Gleason wrote a remembrance of Reed in email that linked to a good interview with him from 2009 that provides some insight into his mindset as an older artist.