Voodoo News: Sundays are For Hangovers and Hanging Out

A slow start and a chill vibe defined the last day of Voodoo 2016.

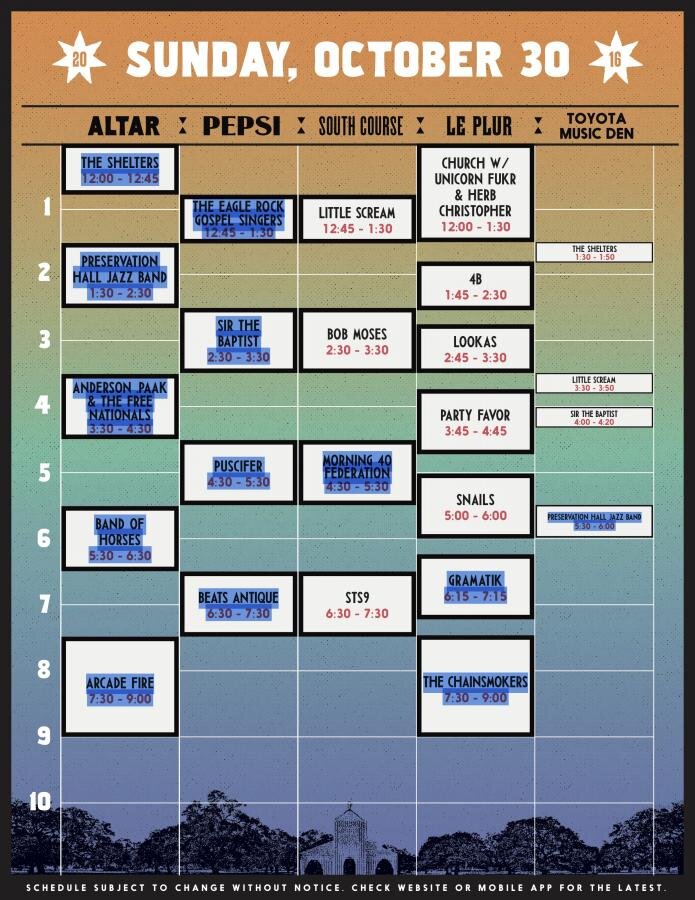

Sunday frequently seems like Voodoo’s afterparty as part of Saturday night’s crowd heads back to wherever for work on Monday, while others never make it back from Frenchmen Street. Those who found their way back yesterday were in no hurry. They had Saturday to sleep off, or they wanted to watch the Saints, and it looks like Voodoo programmed knowing that would be the case. The day started well but with little fanfare. The Shelters opened on the Altar Stage by evoking The British Invasion and the blues rock that would follow, then underlined that impression by closing with a cover of The Yardbirds’ “Lost Woman.”

In the past, Voodoo has nodded to gospel on Sunday mornings, and this year a pair of spiritual acts opened the Pepsi and South Course stages—Eagle Rock Gospel Singers and Little Scream respectively. At 2:30, the Pepsi Stage continued in that vibe with Sir the Baptist, a compelling hip-hop gospel rapper who at the end of the set gave out his cell number. “Now I am your personal prayer line,” he announced. The show had the exuberance and raw passion found in Jazz Fest’s Gospel Tent, and Sir’s rap has musical roots classic gospel as well. Still, his delivery was more contemporary, and nobody at Jazz Fest has done a back flip off a six-foot high stage the way one of Sir’s singers did.

The audience began to find its way back to Voodoo during Anderson .Paak’s set. Paak, like a number of artists on Stones Throw Records, imagines a cratedigger’s vision of R&B history—one where the hip-hop, soul, funk, rare groove and pop R&B that DJs are constantly searching out coexisted rather than competed. Paak and his band The Free Nationals fetishize the sounds of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, so pillowy electric piano chords gently cushioned guitar chicken scratching and “Who’s That Lady” fuzzed guitars.

The open, inviting warmth of Paak’s set made clear by contrast the self-consciously stern effort by Maynard James Keenan’s Puscifer. The set radiated a suspicion of pleasure, and the luchadores who wrestled in the on-stage ring only emphasized that as an oh-so-dada component to the show. Still, Tool fans who couldn’t get enough somber rock ’n’ roll came back for more anyway.

At the same time, Party Favor had issues at Le Plur. According to our Emily Tonn:

The vibe between Party Favor and the crowd never meshed. Favor took a lot of swing and misses as he tried to get the audience to participate in his set, and it made for tangible awkwardness at times, especially when he would dip the music so that people could scream out the lyrics and was met with silence instead.

By 5:30, Le Plur was packed and a peaceful audience chilled all over the Altar lawn for Band of Horses—a group made for late Sunday afternoons. I’ve seen them catch fire in enclosed spaces, but outdoors, words like “pleasant” and “amiable” come to mind. A white wine and brie vendor could have made a killing during their set.

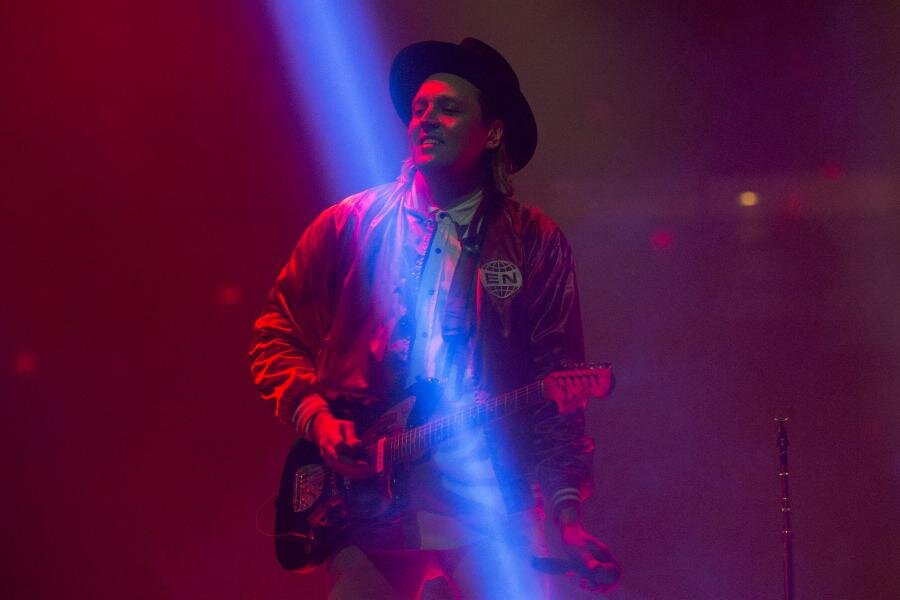

Arcade Fire closed the Altar Stage—and Voodoo as a whole, playing another 20 minutes after The Chainsmokers ended on Le Plur at 9 p.m.—with a set more inspired by Win Butler and Regine Chassagne’s move to New Orleans than a new release. Their set was in keeping with the afterglow vibes Voodoo has historically gone with on Sundays, with reliable, well-loved and respected bands such as R.E.M., The Flaming Lips, Lenny Kravitz, and The Cure. The night before, the band played a private party that featured a number of less-performed songs and a few new ones, but the only nod to new material Sunday was Butler’s attempt to get the crowd to sing a melody that oddly seemed to stump everybody.

Our Raphael Helfand reviewed the set:

Arcade Fire’s 12-piece touring band was massive, but rarely felt excessive. The effects, similarly, were impressive without becoming overbearing, featuring a wall of mirrors (remnants of the tour for their last album, Reflector) that contributed to the light show, but didn’t distract from the music. The rotating instrumentalists played not only the traditional drums, bass, guitar, keyboard, vocals, etc., but also synths, violins, plenty of horns, and an absurd amount of added percussion (two kits and African drum section). The most versatile member of the groups was undoubtedly Régine Chassagne, a founding member (and Win Butler’s wife). She sang (most notably on “The Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains)”), danced in a giant reflective cape, and played drums, keyboard, saxophone and hurdy-gurdy.

Butler, for his part, stuck to the basics, generally occupying the traditional frontman role, occasionally hopping on guitar or keyboard. Still, his giant body, Elvis-like white suit, and hairdo halfway between Skrillex and Clay Matthews helped him dispel any “traditional frontman” conventions before the band played a single note. He mostly stuck to the music, but when he did speak, it was mostly in pointed (if somewhat dated) political commentary. Before starting “Intervention,” he launched into a monologue (his longest of the night) about how he wrote the song during the 2000 election, and related the fear-mongering and Us vs. Them mentality of the Bush campaign to the much worse situation going on today. At a different point, he took the time to let us know that “whatever BP paid the state of Louisiana was a tenth of what it should have been. Fuck British Petroleum!” Even his obligatory I love New Orleans bit had an edge, a not-so-veiled warning against gentrification. (“ A lot of the things we love about this city are being ruined.”) Following this sentiment, he moved into “No Cars Go,” a somewhat problematic choice in that it implies New Orleans should cut itself off, not just from the commodification of its culture, but from commerce in general. Overall, though, his intentions seemed pure enough to let that one pass.

The set was satisfyingly thorough, with a surprisingly equal distribution of songs across each of the band’s four studio albums. Starting out with material from their grammy-winning third album The Suburbs, the band moved into their newest (Reflektor), then went back in time to their sophomore Neon Bible and finally their debut, The Funeral. After a pair of “Neighborhoods” (“Tunnels” and “Power Out”), the set crescendoed with “Rebellion (Lies)” with a little ad libbed riff from the Ghostbusters’ theme song courtesy of Win. Already well past sound curfew, the band plowed on into a Caribbean-tinged rendition of “Here Comes The Night Time” (a brief return to Reflektor) featuring dancers in colorful dresses. Predictably, they closed with “Wake Up,” their breakout hit, donning their characteristic papier måché masks, with even more fully costumed people (the Pope, among others) joining them onstage to add to the Halloween vibes. When Chance the Rapper played Mardi Gras World earlier this month, he tried a similar stunt with puppets, and it came off weird Unlike Chance’s puppets, though, Arcade Fire’s masks felt like just another organic part of the bizarre, beautiful spectacle. Everything felt considered and purposeful, and it made for an amazing show.

Emily considered the set “magical and disorderly,” but we saw one sequence very differently. During “Rebellion (Lies),” Will Butler took over on saxophone in what I thought was a deliberately clowning performance as his body language was that of a man coaxing wailing sounds out of his sax—sounds we couldn’t hear. By the end, I thought Win Butler was goofing on his brother, but Emily saw it this way:

During the set, Will Butler started flailing around the stage with an un-amplified sax in hand, desperately trying to play and then seemingly desperately trying to not to throw up--which I’m still pretty sure he did at one point. A cool Win Butler led the band and forged through the song but no one on stage could mask their reaction--some burrowed their brow in a WTF manner, while others couldn’t help but laugh at the ridiculousness. At the end of the song, Win Butler tried (but failed) to save the slow car crash by helping the crouched saxophonist finish the song on a strong note by singing him through the ending: “C’mon, I know you can do this!” [Note The song died out and it was clear there was no saving the moment so he shrugged off the accident as “the power of music education.” It was funny, weird, uncomfortable, but nothing the crowd couldn’t get over by the time the next song rolled around.

Here are more of our notes and yours on Sunday at Voodoo.