Arcade Fire Gets Serious

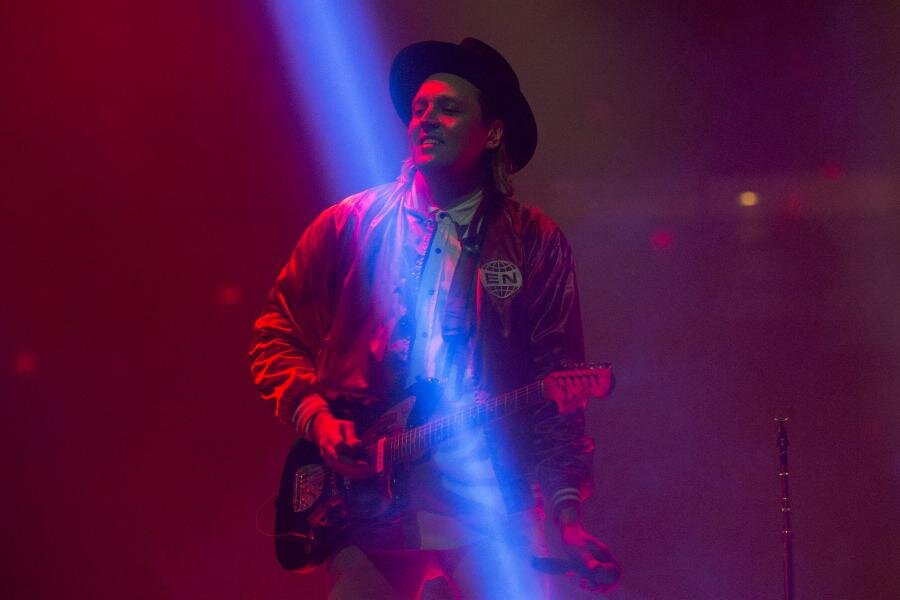

Tuesday night at the UNO Lakefront Arena, Arcade Fire gave their fans a dance party that made the connection between "Everything Now" and its previous albums clearer.

Going into the Arcade Fire show Tuesday night at the UNO Lakefront Arena, the story was that the show didn’t sell particularly well. Two hours later by the end of “Wake Up,” I felt for the people who didn’t buy tickets because they missed a show as compelling as U2’s in the Superdome without the wind of nostalgia at its back. I ended up glad that their absence left room for so many people to dance with abandon at a rock ’n’ roll show.

Doubters have groused about Arcade Fire’s turn toward dance music, but they rarely acknowledge how good the band is at it. When it played disco, disco felt appropriately effortless, and when it veered into heavily sequenced Giorgio Moroder-like electronic dance music, the vibe was sleek and dangerous. “Creature Comfort” from Everything Now segued into “Neighborhood #3 (Power Out)” and together, they played like the rave counter-programmed with the Rapture, with the ukulele and xylophone on the latter replaced by a boatload of distortion that threatened to swallow the song if it didn’t transform it first. In the past, audiences sometimes lived vicariously through the enthusiastic dancing and jumping of band members; Tuesday night, the show gave fans not just the opportunity to dance but an imperative to do so.

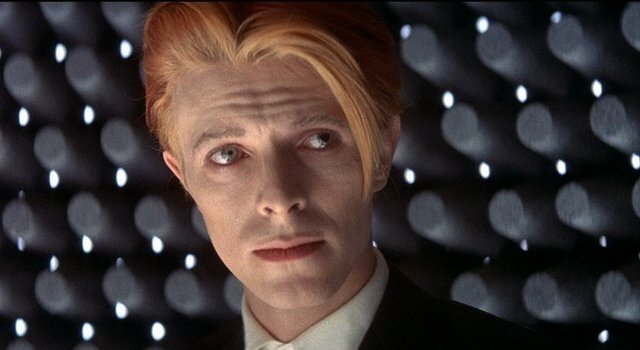

The show started less promisingly. The video screen above the stage periodically featured a cowboy-hatted salesman with a universe for a face who previewed the show in the hyped voice of a 1-800 late night commercial. The reference struck a ‘90s note and was of a piece with the too clever marketing campaign that hurt the reception of Everything Now, and staging the show inside a boxing ring similarly seemed off. Who is the band fighting? Roadies removed the ropes after four songs, and that made it easier to appreciate a stage in the middle of the floor created to foster greater intimacy with the audience. The amount of gear onstage forced band members to perform on the edge of the stage at almost all times. Regine Chassagne did retreat to a drum kit on a rotating platform in the middle of the stage to lay down a rushing beat that made “Neighborhood #1 (Tunnels)” race thrillingly, and Butler sat down at an upright piano on the same rotating riser to play “The Suburbs.” Otherwise, almost all of the action took place on the lips of the stage, just yards from the audience that surrounded it.

The pre-show commercials and boxer comparison—down to a Michael Buffer-like introduction as the band came to the ring—were likely meant to be funny, but Arcade Fire albums and the Everything Now roll-out make it clear that the band doesn’t do jokes. Not well, anyway. Its strength lies in its earnestness. Win Butler’s lyrics as well as his singing of them radiate a desire to say something significant, and I suspect that is something that goads his detractors. Still, Arcade Fire’s best songs effectively explore what it’s like to live five minutes after the good times ended, and they make growing up sound dramatic, whether it happened in the city or in its suburbs. The unironic grandness in the band’s sound makes that upbringing sound meaningful, and when four or five members sing together onstage, it sounds like there’s already a community of people who’ve lived in this neglected space waiting for listeners to join them.

During the encore, Butler put himself in that group by singing, “I want everything now” while strumming his acoustic guitar. He needed to because the Everything Now marketing often presented Butler and the band as scolds wagging their fingers at kids today and all their Internets. Since the online audience embraced the band first and stayed with it longer than many indie rock Flavors of the Month, it was a bad look, and one at odds with many of the album’s songs. In concert, “Daddy how come you’re never around?” comes through “Everything Now” as clearly as the title chant, and “Creature Comfort” shows obvious sympathy and compassion for all the people scaling down their dreams: “God, if you can’t make me famous / at least make it painless.”

For its first three albums, those thoughts took place in the unlikely context of an indie classic rock band—not something people asked for, but they loved it when they heard it. The sentiments and sympathies central to Arcade Fire’s identity are muted in dance music, where the trance imperatives of the groove box out individual moments of grandeur and urgency, and perhaps that accounts for the unsold tickets. Arcade Fire has come to excel at something that works against the impulses that first and solidly connected the band to its audience. The dance music sounds like a natural extension of the members and their affections, and it will be sad if following their muses and the music that speaks most clearly to them prevents Arcade Fire from remaining as popular as its show merits. Unfortunately, the world and the music business in particular are full of aesthetic mousetraps, and there’s no reason to think anyone is immune.

Take the ticket sales out of the story and Arcade Fire succeeded magnificently. By the time the Preservation Hall Jazz Band joined the band onstage for “Wake Up,” Arcade Fire had passed the point where special guests could make the show more exciting. Pres Hall helped the band parade off the stage and back to the dressing room, but the previous two hours defined such a specific, inclusive world that the concert didn’t need a parade band. It was a nod to New Orleans, where Butler and Chassagne live and recorded much of Everything Now, but the rest of the show nodded to the world that the band and the crowd inhabit, and it was more compelling.