Tusk in a Box

Looking for last minute gifts that give you more than you need? Fleetwood Mac, Eugene Mirman and Ork Records have what you need.

The red-blooded American in me loves a box set. Who doesn’t want lots of stuff, particularly if it’s attractively packaged? But the specifics of a box set are the rub. If you’re a fan of the artist, you likely already have much of the material on the box. If you’re not, buying one is a pricey way into an artist. They also rarely hold up from end to end. There’s frequently a disc that presents the artist in process, or one that honors the later material that only diehard fans care about. Or, there’s a disc of outtakes, demos and/or previously unreleased tracks that add little to the story.

This fall, comedian Eugene Mirman mocked the whole idea of the box set with the release of I’m Sorry (You’re Welcome)—a nine-volume, seven-vinyl album set. It includes an hour-long stand-up performance, which is the conventionally funny part of the package. Also packed in are eight more conceptually funny volumes—ones of Mirman crying, “digital drugs” (funny synthesized noises), orgasms, conversational Russian, and ringtones among others. They aren’t tedious—or they aren’t simply tedious—because Mirman signals the game of them fairly quickly in volume two. That is a set of sound effects, all of which he makes with his voice. As a result, they’re terrible sound effects for incredibly specific situations. Mirman announces, “Hero Returning from a Budweiser Commercial,” then sighs heavily three times. “Two Apples on a Rainy Sunday in the Park Watching Failure to Launch” produces a couple of high pitched squeals.

Like so much of Mirman’s comedy, it’s all playfully surreal, and compiling all of these absurd ideas in a box only heightens the madness. Fortunately, you’re only paying for the packaging. The digital version is only $5 more than the average single-disc comedy album—and the stand-up volume is the one part of the collection you might return to—while the vinyl box set is $60. That is a bargain compared to the other ways you might get the album. I’m Sorry (You’re Welcome) also exists in the Robe edition (a robe with an mp3 player with the album for $225), the Chair edition (a chair with a built-in mp3 player with the album for $1,200) and the Puppy edition (sold out).

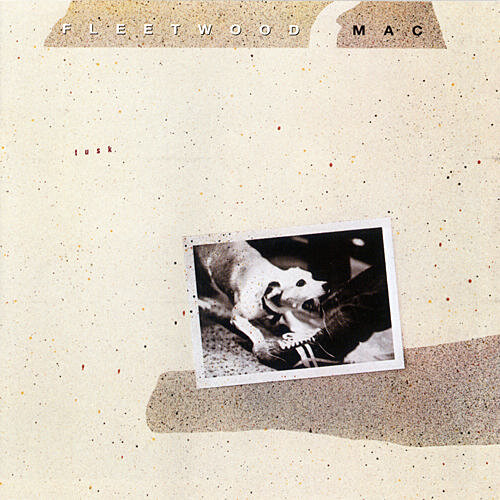

A more conventional box set is the reissue of Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk, which documents the band’s 1979 follow-up to Rumours in exhausting detail. You get the album, an alternative version of the album (made from the next-most-interesting takes), other versions, demos, and leftovers, the band live on the “Tusk” tour, a DVD mix, and the original two record set on vinyl. All of that adds up to an impressive monument to a curious album.

By the time Fleetwood Mac was ready to return to the studio after Rumours and touring had run their course, Lindsay Buckingham had become fascinated with punk and the first flickers of new wave. He cut his hippie hair, shaved his beard, and seemed strident in his desire to not make another record that sounded like Fleetwood Mac. The band’s soap operatic existence was continuing as Stevie Nicks became a celebrity, then found herself replaced in Mick Fleetwood’s life by her best friend. Those circumstances, combined with the privilege the band had after becoming the biggest band in the world, led to Tusk—an album that remains a fascinating mess.

Tusk is the Fleetwood Mac album for people who are ambivalent about Fleetwood Mac, and the title track is its appropriate emblem. It’s not clear how the lyrics fit together or who is saying what to whom. Sonically, it remains odd with Nicks and Christine McVie’s songs sounding as lush and Southern Californian as ever, while Buckingham deliberately employs scrubby, abrasive guitar textures and extreme vocal performances, barking his lyrics in tightly focused fragments of songs. Today, he sounds at war with his band, and it’s a testament to the weird bonds inside a band that Fleetwood Mac survived Tusk. Like Rumours, the album presents a lot of brokenhearted lovers talking to each other across well-crafted songs, and it’s often pretty compelling as a whole, perhaps because it didn’t become a singles machine the way Rumours did. Still, many of Buckingham’s contributions make it sound like he’s singing to someone in a different band.

The outtakes from Rumours helped me hear the blues in that material that wasn't obvious in its final form, and those from Tusk shed similar light on some tracks. The multiple takes of the title song including the USC Marching Band version all confirm that the song is bulletproof. Six tries at “I Know I’m Not Wrong” show Buckingham searching for the right sound and feel for the song, but what becomes clear is that the song is not so compelling that any take seems more right than any of the others. “Sara,” Stevie Nicks’ signature contribution to the album, began as an eight-minute story-song, and the demo feels at least that long. The version the band recorded is almost as tedious, and it made me want the sort of surging interplay The Band exhibited while backing Dylan to give it some energy. For the final release, the track was cut down to six minutes that still test my patience, but the live version gives the song life. A slightly brisker tempo helps, as does a circular picking pattern that Buckingham plays to give the song the motion it needs.

Lindsay Buckingham would never sound this extreme again, and Fleetwood Mac would never be this enigmatic again. Its chemistry would never been as productively volatile again, and changing musical tastes made lush Southern Californian pop seem old school. Still, 1979 no punk band put more on the line than Fleetwood Mac did with Tusk.

This week’s announcement that the landmark punk club CBGB would reopen as a restaurant in the Newark Airport launched a thousand wisecracks on Facebook. The club once located in New York’s Bowery helped start the careers of Patti Smith, Television, The Ramones, Talking Heads and Blondie, and the recently released the two-CDs-and-a-book Ork Records: New York, New York fills in some blanks in that story by telling us who played on the nights between its brightest stars. Ork Records was the brainchild of Terry Ork, one of the countless people who invented himself in New York in the early 1970s. He worked on Warhol films, in a video store for film buffs, and began managing rock bands starting with Television. In many ways, he was the prototype punk manager/label—an enthusiast with more passion than business sense who kept money moving in such a way that he got more than he could actually afford—most of the time.

Because of that, this reissue from The Numero Group releases some songs for the first time as it pulls together songs by Television, The Feelies, Richard Hell, Alex Chilton and Chris Stamey and such lesser known acts as The Student Teachers, Prix, The Revelons, and Erasers. As a document, Ork Records: New York, New York is revealing as it presents the ragged excitement of young bands who felt like they were a part of a moment playing with more passion than precision. Because the studios they recorded in were often shitty, the records are more about energy than music, but if you have an ear for the drama that plays out on the album, it’s always at least listenable.

Ork’s tastes aren’t easy to pin down on the album, and it would be a mistake to assume that he felt equally excited about each project. It’s likely that there were some records that he thought would help pay for records by bands he cared about more, and there are bands that he recorded because they were the best ones still available after Sire and other labels had signed the ones he really wanted. It’s entirely possible that there are records here that Ork released because he was sleeping with—or wanted to sleep with—someone in the band. Or someone was a drug buddy. Deals were made on such flimsy stuff then and likely are now as well.

There are a lot of good songs on Ork Records: New York, New York, but for me its success is the collection’s ability to convey a moment when everything seemed possible. Maybe stars didn’t have to be classically beautiful or handsome, and maybe chops were overrated. Maybe there was a place in the musical world for a less glamorous, working class culture that spoke to the ways people really lived as opposed to the way they were told they should. Much of that proved to be true a decade or so later, and the Ork collection is in many ways a truer expression of where the indie spirit started. The best from that era did something so well that they eventually reached a national audience; many of the artists included here did it well enough to reach the one right in front of them.