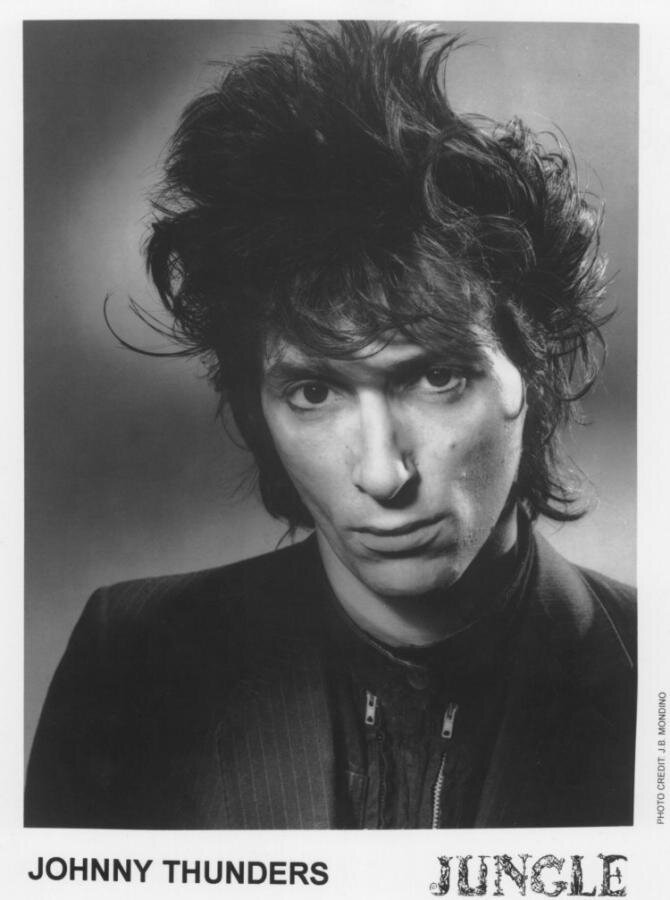

Still Looking for Thunders

The documentary "Looking for Johnny" only tells part of rock guitarist Johnny Thunders' story.

It’s pretty much a given that the makers of music documentaries are too in love with their subjects to do the job. The DVD of Looking for Johnny—a documentary on The New York Dolls and Heartbreakers’ Johnny Thunders—was released late last year, and it further illustrates this point. The film’s not too long, which is usually the problem, nor does director Danny Garcia obsess over fan-only minutiae in Thunders’ life. In fact, he provides a good, clear account of how a drug-free, high school baseball star John Genzale became Johnny Heroinseed, the punk rock guitar hero who left a trail of junkies behind him.

Garcia assembles a who’s who of New York underground rock folks from the 1970s, all of whom knew and loved Thunders, and they tell the story of the impact of The New York Dolls and The Heartbreakers, the latter of which did as much to shape the sound of British punk rock as The Ramones when the band toured England. Thunders’ raunchy, slurred approximation of Chuck Berry’s guitar style was massively influential, and the no-frills directness of the band gave a thousand punk wannabes a blueprint for channelling their anger and energy.

The friends talk about how talented Thunders was (which is true), what a sweetheart he was (which is possible), and how prolific he was (which is false). If all you hear are The New York Dolls' self-titled debut album and Too Much, Too Soon, The Heartbreakers’ Live at Max’s Kansas City '79 and his solo album, So Alone, you’ll have heard the music that makes a claim for Thunders’ greatness. There are other good tracks, but there’s a lot of half-assed shit as well, recordings padded with unconvincing acoustic versions of previously released songs or remakes of older songs, all of which make many of his releases sound like yet another junkie hustle.

What Garcia didn’t find was anyone who’d say what a waste it was that heroin slowed his output and dulled his brain. That the accompanying desperation led him to release sub-par music when he needed a few bucks. People talked about what a shame it was that he died at age 37, but nobody said anything about the way his junkie wipeout persona turned his gigs into sideshows, where fans ghoulishly waited for mumbling, audience-baiting breakdowns or—secretly—an onstage OD.

Nor does Garcia get close to the reason Thunders made the drastic turn that he did. Looking for Johnny mentions a largely absent father, but little is made of that. The doc credits New York Dolls drummer Billy Murcia for turning Thunders on to heroin, but there’s no accounting for why it took like a motherfucker. Garcia has some compelling footage of Thunders that he filters through the documentary, but Thunders is too drug-damaged to be emotionally engaged or articulate, and years of talking around drug-related issues made him habitually evasive. His charisma still shines through in those clips, but Thunders doesn’t give viewers a reason to connect to him.

Thunders’ last chapter took place in New Orleans when he made the spectacularly bad decision to try to clean up here in 1991. He didn’t last 24 hours and was found dead over the toilet in a guest house on St. Peter Street in the French Quarter. Garcia only scratches the surface of controversies and conspiracy theories that surround his death, but that’s consistent with the affectionate tone of Looking for Johnny. He does a good job of elaborating on the last chapter of Thunders’ career when he spent more time in Europe, and the film consistently puts Thunders in the best possible light. Still, there was a far more dramatic story to tell.

One final note: Writers Jon Savage and Greil Marcus have linked The Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren to the avant-garde Situationist art movement. Their arguments make sense (I think Savage’s England’s Dreaming is one of the best books on British punk), but after hearing audio clips of McLaren talking about his efforts to manage the last incarnation of The New York Dolls in Looking for Johnny, I’m more sympathetic to NME writer Nick Kent’s take. In his book Apathy for the Devil: A ’70s Memoir, Kent argues that McLaren was better understood in context of the long line of British pop star managers who were profoundly cynical toward the marketplace, music and fans, and while I can’t quite buy that either—who’d really think that remaking the Dolls as Communist propagandists in the mid-‘70s was a way to financial gold?—his indifference to the talents at his disposal and to the personal impact of having a band’s career turned into into a joke makes it hard for me connect to any understanding that gives McLaren the benefit of the doubt.