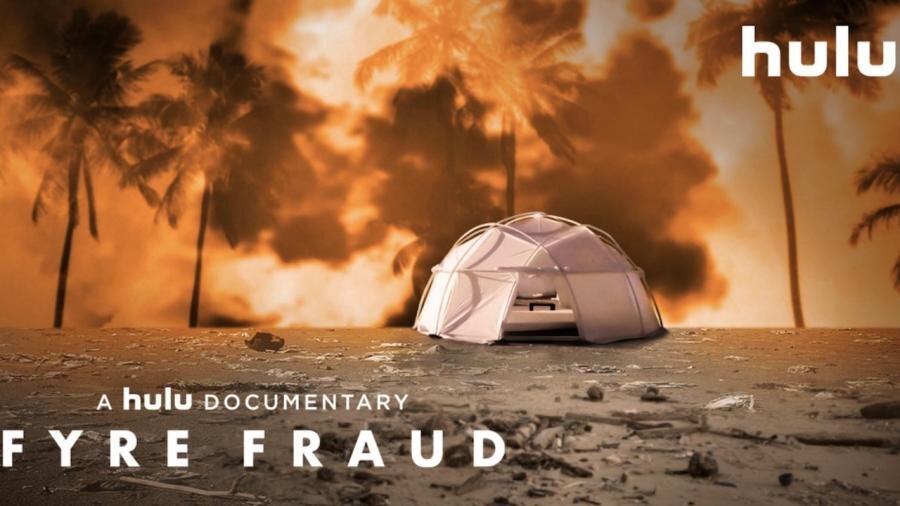

Playing with Fyre

Two new documentaries on Hulu and Netflix speak to broader issues than just the failed music festival and its inexplicable promoter, Billy McFarlane.

Two documentaries on 2017’s disastrous Fyre Festival failed to crack the nut that is Billy McFarland. Neither Hulu’s Fyre Fraud and Netflix’s Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened explain how McFarland managed to float the financing to make the festival look like it might actually happen, though in reality, it doesn’t sound like it was ever close. Fyre Fraud lets you know about all the financial games he played to keep the dream/scam afloat, but neither explains how he did it. How did such a blandly handsome bro convince people to keep pouring money into his failing plan. Fraudulent documents certainly helped, but people in both documentaries talk about a charisma and persuasiveness that doesn’t make its way to the screen. Instead, we see a Gump-like figure or a Chauncey Gardiner Jet-Skiing around the Bahamas with a beer in his hand while New York’s young(ish) and monied class projected their hopes and dreams on him. Maybe he just seemed like such a dolt that no one could imagine that he was scamming them, or maybe he was so delusional that he could lie with a straight face because he really believed in his crazy scheme.

Both documentaries are worth seeing since Fyre Fraud spells out the details of McFarland’s scams, while Fyre reveals the human consequences of them in the Bahamas. The Netflix doc tells a better story, but the Hulu has better information. My favorite at so many levels: McFarland explaining that he really had rented villas and cars for high rollers—despite all evidence to the contrary—but he lost the box with the keys. #mydogatemyhomework

Or, the way he blew up his own game right from the start. One of the few true things that McFarland said was that the island in the Bahamas he envisioned as the site for the festival had in fact been a residence for the famed drug lord Pablo Escobar. According to one of the documentaries, the owner of the island was open to the Fyre Festival because he wanted to rebrand the island and leave its notorious past behind. When the advertising video promoting Fyre Festival announced that the island was owned by Escobar about 40 seconds in, McFarland lost his white sand beaches and crystal clear blue water and had to relocate to a snaking patch of hardpan adjacent to the Bahamian resort Sandals, itself a resort that delivers more faux eleganza than the real deal.

Both documentaries highlight the schadenfreude evident in the social media mockery of those who found themselves stranded at the gravel pit after buying into Fyre Festival’s promo video and the living large party it promised. The “Eat the Rich” vibes were strong, but my hostility was more specific. McFarland and co-conspirator Ja Rule toasted to “Living like movie stars, partying like rock stars and fucking like porn stars,” and the people who thought that was a) desirable, and b) possible if they just spent enough money, deserved a night or two of Lord of the Flies. By the time we’re nine or 10 years old, we’re told that if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is, so it’s hard to feel for people who hoodwinked themselves, or who believed that their money made them shrewder than everybody else. If people thought they were going to get to party with Kendall Jenner and Bella Habib, again, they deserved what they got. They had to know that even at a festival of only 10,000 people, the richest, most beautiful people were going to be kept separate and above the merely rich and beautiful people.

The conflation of Escobar’s island and the promise of the star life is by itself interesting and provides the easiest way to appreciate Capitalism circa 2017. If you have enough money, you can live a life that is above the law and indulgent on every level. And, if you have enough money, you can be a bigger outlaw and more indulgent than those around you. Day tickets of a measly $500 bought on the general admission experience, while $12,000 promised a VIP experience. Never mind that Fyre and McFarland couldn’t deliver any of those things; the elaborate pricing structure spelled out the way that even when the wealthy meet the wealthy, they want markers to demonstrate who has more money than who, and they want to know that their extra wealth entitled them to something more and better than those with less. Money has to mean something.

The festival began as a marketing event to launch the Fyre app, an Uber-like platform that would allow people who wanted celebrities at their events to negotiate with them directly. Both documentaries take the app seriously, in part because the people who worked on it did so in good faith and were part of the collateral damage as the Fyre Festival imploded. Nobody questions the premise, that there’s something intrinsically worthwhile about paying celebrities to come to your parties, and that the celebrities at your party would say anything more about you than you could afford to pay celebrities to come to your party.

The Fyre app, the festival, and the festival’s promise combine to reveal the lie at the heart of the Republican vision of concentrating money in the hands of people who can create jobs. The wealthy could start businesses that employ people, or they could pursue class distinctions insides class distinctions and indulgence inside indulgent experiences. They could fancy themselves outlaws within the safety of their money. The class war vibe on social media accompanied the joy of seeing people stuck on Great Exuma in a situation where their money couldn’t save them.

VIDEO

Fyre Fraud and Fyre are required viewing in part because the interplay of wealth, fame, and rock ’n’ roll resonates in a number of ways. Watching them, I felt like I understood Post Malone’s success and the Trump presidency. And in the Fyre app coders, festival employees, and Bahamian day laborers, we saw that the people who were actually suckers enough to do work were screwed in very real ways.

The story is also a distinctly digital era story. Festivals have failed in the past and some likely failed just as spectacularly, but the Fyre Festival could only have happened now. Do “influencers” have influence because the way their seemingly casual thoughts and shots turn up in the Instagram feeds makes readers feel close to them or trust them? At their hearts, the documentaries explore the relationship between our digital and actual selves, and how the digital realm made it possible for so many people involved to live beyond their means.