Lost Bayou Ramblers, Louis Michot Are More Traditional Than You Think

Their 21st century version of Cajun music and their side projects suggest new ways to think about tradition and authenticity.

[Updated] The Lost Bayou Ramblers’ documentary On Va Continuer presents the band and particularly fiddler Louis Michot as traditionalists. That’s a very familiar narrative for the band; soon after it formed in 1999, The Lost Bayou Ramblers came to be seen as part of a new community of history-minded young bands in South Louisiana that included The Pine Leaf Boys, The Red Stick Ramblers, and Feufollet. Rather than look to contemporary music for ideas about where to go with traditional music, they scoured Cajun and Creole music’s past.

Frequently, artists and fans who embrace tradition use yesterday as a stick to beat today. It often represents a retreat to a better time that probably wasn’t really better, but the Ramblers and their contemporaries looked back with a hip-hop DJ’s sensibility to see what new music can be made from the old stuff. Instead of focusing on the biggest, most influential figures, they looked back with a more specific focus. On the 2006 album Lost Bayou Ramblers present the Mello Joy Boys, they were joined by Pine Leaf Boys Wilson Savoy and Jon Bertrand to emulate the swing bands that played along the then-porous border between Louisiana and Texas, performing music that nodded to both states’ traditions.

On Saturday, Louis Michot will play with another of his bands, Michot’s Melody Makers, at The White Roach used record store when it has an in-store showcase with Sharks Teeth and Jonny Campos and the Hunks.

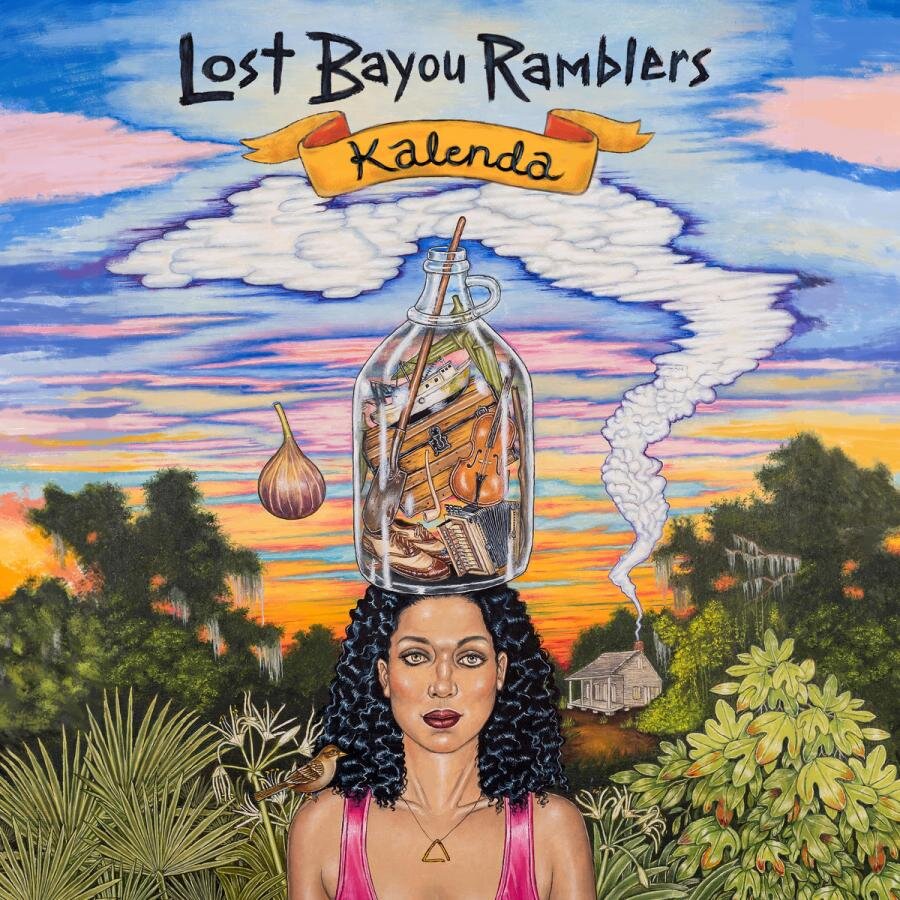

In On Va Continuer, Michot talks with his brother Andre and his father Tommy about the way they grew up playing Cajun music and learned from their father’s band, Les Freres Michot. We also see Louis try out new fiddles and Andre explain how he learned the time-consuming process of tuning an accordion. As specific as those sequences are, the scene that sets the documentary apart from other music documentaries comes early in the film when the camera follows Louis as he backs his pickup to the bayou’s edge and rolls his trailer back down a steep bank to put his boat in the water. We haven’t seen other musicians back their boats into rivers or streams, much less bayous, and they certainly didn’t tool around to explain how the waterways they motored through used to be important transportation thoroughfares. The Lost Bayou Ramblers won a Grammy for 2017’s Kalenda, and On Va Continuer presents the win as a victory for tradition.

At the end of the movie, Michot says, "Music is possibly the best vehicle for transmitting this language and processing how it applies to us today," and moments later, we see exactly what that means. For much of the movie, the band plays music that sounds more or less traditional, particularly if you don’t listen to much traditional Cajun and Creole music. The final sequence presents the band onstage at One Eyed Jacks pounding out a version of Cajun music that moves with a conventional, cyclonic energy, punctuated by unconventionally spongy, beefy drums that stomp like a dinosaur. The song is "Freetown Crawl/Fighten'ville Brawl" from Kalenda and the drone central to so much Cajun music is present, but Andre feeds his accordion through a wah-wah pedal to mess with it while guitarist Jonny Campos distorts his electric guitar through a series of pedals as well. It’s heavy as hell, and traditionalists who have a specific notion of what Cajun music should sound like get skittish around The Lost Bayou Ramblers because the band can sound familiar and deeply rooted, but it can also sound like this.

On Va Continuer! The Lost Bayou Ramblers Rockumentary from Worklight Pictures on Vimeo.

That sound is certainly part of Kalenda. It’s tempting to say that the album features the band’s adventurous side as much as its traditional side, but there really aren’t two (or more) sides to Lost Bayou Ramblers. They’ve been traditional in the way they honor their culture and the impulses behind the music, but they’ve never been purists. Cajun bands historically didn’t include drummers, whether snare drummers like Chris Courville—their first drummer, who Michot met while playing Led Zeppelin covers—or pounders behind full kits, like current drummers Eric Heigle and Kirkland Middleton. They’re not alone in the way they bridge disparate influences. Feufollet sounds like an Acadian art-pop band when it covers Eno, The Beach Boys, and Big Star, and neither band treats Cajun and Creole music like a place to hide from the larger music community. In 2011, Michot spearheaded the compilation album, En Français, which featured young Cajun bands including Feufollet and Lost Bayou Ramblers playing classic rock covers. Appropriately, The Lost Bayou Ramblers covered The Who’s “Ma Génération.”

When the Ramblers back up The Pogues’ Spider Stacy to play Pogues songs under the name Poguetry, the shows sound like a natural extension of the Ramblers and debunk the theory that cultures are impenetrable, stony monoliths to be worshipped. Poguetry shows instead that cultures are porous, amorphous entities to engage and cross-pollinate. Stacy added his penny whistle to Kalenda, and in concert, Michot sings The Pogues’ “Dirty Old Town” in English and Cajun French. This year, Michot also joined Creole cellist Leyla McCalla on her The Capitalist Blues, produced The Rayo Brothers’ Victim & Villain, helping them move from faux Dust Bowl balladeers to make songs that are more distinctly them. “They’re country boys,” Michot says. “They lived a normal Acadiana country life. It’s a refreshing, modern take on country.”

In 2018, Michot launched his own record label, Nouveau Electric, which is home to the Rayo Brothers’ album. He’d gone through the heartache of working on album, pinning hopes to its reception, then having the album disappear into the flood of other releases and end up living a lonely existence on the band’s merch table, only available at shows. “I’m trying to bring my experience and what I’ve learned as an independent artist to try to help other people get their music out more efficiently without it getting lost in the universe of music, that is, like, a thousand releases a day,” Michot says.

So far, Nouveau Electric has released eight recordings by six artists, ranging from the electronic, sample-based singles by the Levee Bandits to the a cappella songs on Chansons de la Campagne by Ethel Mae Bourque, who was 70 when Michot recorded her singing the songs in 2003. Her husband, Sydney, appeared on the cover of The Lost Bayou Ramblers’ 2005 album, Bayou Perdu, and the couple were the Michots’ neighbors. They served as conduits to the Michots’ Cajun culture and traditions—traditions that remain parts of their lives. On the morning we talked, Michot started the day by helping a friend harvest crawfish.

“He held my little baby while I sacked the crawfish,” he says.

Last spring, Michot recorded performances by 101-year-old fiddle player Willie Durisseau, who played house dances in the 1930s until he went to World War II. Durisseau’s not a lost legend or a pioneer. He was a working musician who could show Michot how people used to play. When Durisseau performed in front of Michot’s mic, he didn’t play for very long—“understandable at 101,” Michot says. When he played longer, he only did so to entertain Michot’s young son. The results were songs from a different era and a window into a different approach to music. Neither Durisseau or Bourque thought of their songs as anything special, and they certainly didn’t think of themselves as artists. They didn’t have the perspective to appreciate their songs as anything other than the things they played at dances or sang to make time pass while working. They were entertaining themselves or others, and couldn’t hear the music they made as artifacts of a culture and way of life that is hard to access in the 21st century.

Michot hopes to release the recordings on Nouveau Electric, but the experience of working with Durisseau was rewarding in the same way that Michot enjoyed recording Ethel Mae Bourque. He got to listen to them talk about growing up in South Louisiana, although he found that like many old people, they didn’t respond well to direct questioning. “But they’ll remember the good stories if you let them think and talk,” he says.

Nouveau Electric isn’t only a home for folklife recordings, though. In 2016, avant garde saxophonist John Zorn invited Michot to play a six-night residency at his venue, The Stone in New York’s East Village. Michot plans to release some of the music from that week, which demonstrated the range of his interests. He performed with many of the projects he has been associated with including The Lost Bayou Ramblers and a reunion of the Mello Joy Boys, but he also performed for the first time with the New York-based violin duo String Noise and Leyla McCalla, and performed the soundtrack to the 2012 film Beasts of the Southern Wild—which prominently featured his fiddle and voice—with the Wordless Music Orchestra. He also collaborated with Spider Stacy and the multi-disciplinary artist Charlélie Couture, who Michot met at Festival International in Lafayette. Some sets featured material that was well-rehearsed while others were improvised.

One of the bands he played with was Michot’s Melody Makers, and it’s the only one that on paper seems like it encroaches on Ramblers territory. Louis says that’s not the case. “It’s Creole music; it’s bluesy,” Louis says, but that’s only part of the difference. When Michot worked as a rep for Bayou Teche Brewery in Arnaudville, he had club owners ask him if he could play their venues. He began putting together bands to play those dates including Soul Creole, a duo gig with accordion player Corey Ledet. While in New York City on a promo trip for Bayou Teche, he played for the first time as Michot’s Melody Makers with Jonny Campos, Korey Richie, and free jazz drummer Jason Ribera. The band’s lineup has changed a number of times since, but its fixed point has been Michot’s pursuit of another Cajun tradition. Willie Durisseau told him that when he played dances in the 1930s, no one played accordion, and that’s the thread that Michot’s Melody Makers picks up. “It’s me trying to explore this fiddle repertoire that was pre-accordion while at the same time doing my own thing,” Michot says.

The Ramblers, Michot says, are in a good place, and they remain active. They’ll go on tour in February to play Poguetry shows with Spider Stacy and Cait O'Riordan, bracketing the Pogues music with Lost Bayou Ramblers sets. They took a hiatus in 2018, but it became nothing more than a break from live shows. During that time, they recorded the soundtrack for the movie Lost Bayou that played at the New Orleans Film Festival last year, and they worked on On Va Continuer. “It wasn’t much of a break,” Louis says, laughing. Last year, the band celebrated 20 years, which passed the way 20 years in a band tend to pass. It started as family and friends, and as is always the case in situations like that, changes followed. Andre and Louis added other musicians, some of whom worked out and some who had different visions for where the band should go. Now Michot doesn’t want to tour as much as they used to, so he thinks it’s important that band members understand and appreciate Louisiana as a musical marketplace.

“We’re so fortunate to be able to play locally so much,” he says.

The band now includes Michot, his brother Andre, guitarist Jonny Campos, formerly of the indie rock band Brass Bed who also plays in Jonny Campos and The Hunks, drummer Eric Heigle, who is also an engineer and producer. Bassist Bryan Webre and drummer Kirkland Middleton are members of Michot’s Melody Makers (along with producer Mark Bingham), and they have other side gigs as well. Those other interests and demands on their time might create logistical challenges, but Michot says that the worst times for the band came when members needed the Ramblers to be their sole artistic outlet and financial engine. He’s happy that that’s not the case now. “We have multiple bands, multiple creative outlets, and multiple ways of making money.”

The current state of the band is validated in part by the Grammy win, but the Ramblers haven’t been a journey in search of this musical place. “Andre and I have always been down to be progressive and creative, but we’ve always been happy with where the band was at,” Louis says. In their minds, they’ve always been traditional and authentic, but if you watch crowds at festivals like Jazz Fest—places that draw casual fans as well as fans of the genre—you can see that not everyone hears their music their way. In fact, those who camp out at the Sheraton New Orleans Fais Do-Do Stage are likely to sit, arms crossed while listeners from other stages move in and react enthusiastically to the Ramblers.

“People that don’t know Cajun music, they like us because they like us,” Michot says. “For people who are into Cajun music, there’s a weird lag that happens where a lot of people are still stuck in the ‘80s and ‘90s and this vision of what Cajun music is supposed to be. We were reaching back to the ’20s and ‘30s.” That was part of the Michots’ process of learning the roots and getting the classics under their belts so that they knew the music that the culture was built on. They learned in the process that if they really wanted to be traditional and follow their musical forefathers, they had to go in unexpected places.

“When we got more comfortable, we started experimenting more, but we were still influenced by this older generation of musicians who were doing wilder stuff than the modern musicians were doing,” Louis says. “They were integrating pop music and jazz music and swing music and blues and everything they were hearing in the larger region around them, and meeting other musicians. You can’t not be influenced when you’re Amédé Ardoin and you’re in New York City, taking a bus up there that almost sank in the Hudson River on a ferry. These experiences are informing your art. Or Mayuse Lafleur and Leo Soileau hanging out in Atlanta with Jimmie Rodgers drinking prescription liquor. Must have been like going to Oregon today where things are legal there that aren’t legal here. There’s always that idea of ‘traditional’ and ‘authentic’ that is behind the times. Really, what’s authentic is what’s happening now that you haven’t even heard yet.”

When many people think of “Cajun music,” they imagine the sound they heard when they first heard Cajun music in the ‘80s and ’90s, and they consider that traditional because that’s the framework in which they heard it. That approach is well-meant, but it creates a bind for musicians that play in traditional fields today. They can treat the music as a set of sounds and songs to recreate like a very niche cover band and make one audience very happy, or they can treat the music as a vocabulary and an approach and make music that reflect the times they live in, just as their forerunners did. Lost Bayou Ramblers went the second way, and the audience for respectful recreations of old sounds came along grudgingly.

“As soon as we started progressing, they told us, Oh, we like your old stuff,” Michot says.

On Va Continuer! The Lost Bayou Ramblers Rockumentary from Worklight Pictures on Vimeo.

Updated January 29 at 11:02 p.m.

The title of On Va Continuer has been correctly spelled throughout the story.