Last Night: Wynton, JALC In and Out of Balance

Ellis Marsalis contributed a curious, needed moment in Wynton Marsalis' Sunday night show at the Saenger, according to guest reviewer Brian Boyles.

Ellis Marsalis contributed a curious, needed moment in Wynton Marsalis' Sunday night show at the Saenger, according to guest reviewer Brian Boyles.

Sunday night, Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra performed at the Saenger. The People Say Project's Brian Boyles contributed this guest review. We're pleased to have Boyles' voice back at My Spilt Milk. Earlier this year, he covered Lil' Boosie's post-incarceration press conference for us as well.

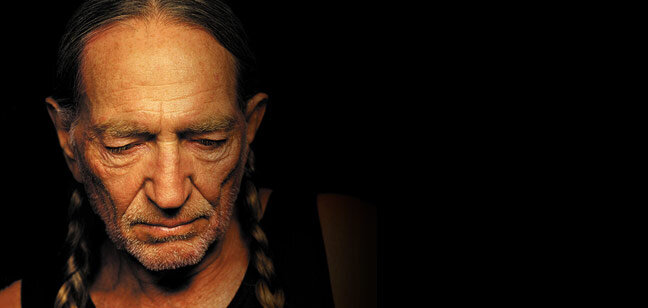

There was a rare moment of imbalance at the Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra’s concert benefitting Tipitina's Foundation on Sunday night. In the idyllic Saenger Theatre, about an hour after the mayor’s introduction, Marsalis announced the next song as a Horace Silver composition that, “back in the late ‘70’s,” he and others struggled to master as NOCCA students. Back then his father was his teacher, so he asked Ellis Marsalis to join the orchestra for “Senor Blues.” Ellis appeared at the top of the center aisle and made his way through a standing ovation to wait in the wings as the band began.

A few minutes later, Ellis came out to relieve deep thinker Dan Nimmer of the piano bench. The orchestra drew down and the modernist played the hippest thing I’ve heard in months. Ellis was minimal but dazzling, just a few bars of mastery, and somewhat Monkish but with a quick, personalized run. You were primed to appreciate whatever he did, this honored guest, but then he did something so…cool.

The band rejoined, and it was evident that Ellis was unfamiliar with this particular arrangement of Silver’s standard. Nimmer came over to turn the sheet music, even jumped in for some solo chords, but mostly the older man stayed at the low end of the piano until the song closed. It created a tension—would they round back to Ellis or would he catch up? He didn’t need to, of course. The figure he cut wasn’t imposing, but it set things askew, a bit tense. His solo overshadowed the remainder of the song.

If you can’t enjoy JALC for its technical brilliance and didactic purpose, you’re missing out. When they perform Wynton’s favorites rather than one of his grand suites, you appreciate the original democratic/encyclopedic function he envisioned when first he plotted a palace. Yes, it’s almost all canonical, but it’s a great canon, and now that Wynton has established it for eternity, fortified it, and proven he’s not knocking down any other walls, you have to thank him for putting Ryan Kison, Victor Goines, Nimmer, Chris Crenshaw and the rest on the task of defending the music. Does it sacrifice adventure? Perhaps, but these are adventurous players who carry on Ellington through the diversity of voices united in song. The jazz-is-America point was always good. The efforts to exclude, not so much, but bygones….

They performed a Mulgrew Miller composition that was grand and soulful and made me want to hear more of the Mississippian’s work, which is the point of the enterprise. They killed at Brubeck, as you might imagine. Wynton didn’t play as much as anyone wanted and when he did, the reliance on a plunger fell flat for me. Sure, there’s a poetry to the restraint, to the plaintive voicing, but why hold back? The material was all there and the band cooks. We’re not asking him to break ground, just to display that fiery virtuosity in service to the tradition.

Alas, the goal is vigorous homage, and homage is important amid this violent flux. Imbalance comes, improbably, at the fingertips of the father. We might wish Wynton set more scores on fire, but he defined his role long ago. To hear JALC is to hear a vision realized. It was nice, for a moment, to hear it disrupted, too.