The Mekons: Still Punk Rock After All These Years

Joe Angio's documentary "Revenge of The Mekons" depicts a band whose continued existence flips a defiant bird to a music industry that could never figure out what to do with it.

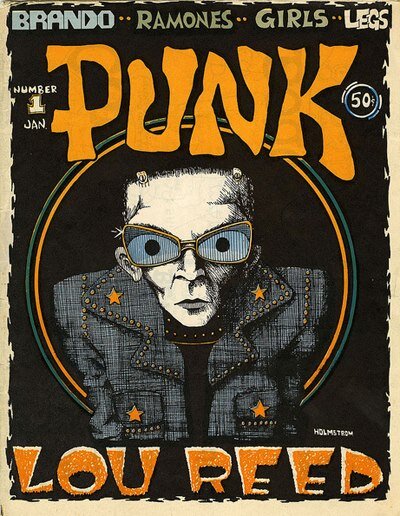

When opportunity knocked, The Mekons pretended they weren’t home. Actually, that’s not true. They just didn’t stop what they were doing to answer the door. The British punk band were art school mates with the Gang of Four and recorded their answer to The Clash’s “White Riot”—“Never Been in a Riot”—in 1978. At the time, primitive skills were badges of honor in the fight against the tyranny of technique as embodied by Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Eric Clapton, and any musician who intentionally played in 11/4 time. The Mekons were as raw as anybody and as pure as punk got, but for them it was an ethos of self-definition, not a sound.

Because of that, the band found champions but not financial success, and in the early ‘80s, they went dormant. The Mekons never officially quit though. In 1985 they released the first of a series of albums that found them a new audience and established them as icons of clear-eyed integrity. Fear and Whiskey is defined by Tom Greenhalgh’s yowl, “Hard to be, hard to be human again,” with others singing along with boozy passion as if it’s a sentiment to rally around, a football cheer for the dispossessed.

Critic Robert Christgau wrote, “What Greenhalgh is desperate about is a literally revolutionary scenario in which the government has routed rebels who swear they'll regroup but find themselves bogged down in alcoholic angst on a highway that's lost the way a beachhead is lost.” Grail Marcus similarly observed, “This is the music of a small group of people who, in a pop moment now almost a decade gone, once thought all things were possible, and who now live in a society where nothing they want is possible as more than an evanescence.”

Fear and Whiskey framed The Mekons as a country band of sorts, tapping into the way country spoke for the working class. Theirs was a rowdy, literary, political version of country with oddly shaped songs that referenced Dashiell Hammett as readily as Hank Williams. For the decade that followed, they recorded a series of albums that would make them the dream band for grad students everywhere—a band smart enough and drunk enough and political enough to make their own lives seem revolutionary through the transitive properties of rock ’n’ roll. When Jon Langford sang “Destroy your safe and happy lives,” it was a rallying cry for thousands who loved the idea more than actually doing it.

Joe Angio’s 2013 documentary Revenge of the Mekons presents the band as a survivors’ story, an example of the power of positive failure. The movie will show at Zeitgeist Multi-Disciplinary Arts Center Friday night at 9:30, and Angio and Langford will be on hand to introduce the movie and answer questions afterward.

The movie began in proper Mekons fashion as something else. Angio knew he wanted to do a music documentary and had one on Yo La Tengo in pre-production. When it fell through, he went to his wall of albums and simply started considering who he liked and who’d make a good movie. “When I got to my sizable collection of Mekons albums, I stopped right there. It was almost a Eureka! moment,” he says. He knew the band’s history, its politics, its background in art, and knew that their story came with questions worth exploring.

“How does a band who’s never made it by any ‘conventional’ definition of making it with eight members living across three continents—not only how to they survive but given their lack of any conventional success, why do they bother?” he wondered.

Not surprising, it’s a premise that didn’t always sit easily with the band. Once Revenge of the Mekons was out, Langford and The Mekons’ Sally Timms started to be asked about the movie while on tour, and Timms took the question as an implied admonition that it might be time to pack it in. She told Zachary Lipez at Noisey:

I do feel like Joe started with the premise, “why do they continue to do this?” And that did bug me, and I said that to him, it's like that isn’t a question that ever comes into my mind, my question is “why wouldn’t we continue to do this?” We get to travel, we get to go all around—well not all around the world, but we definitely go to nice places. So that was what bugs me. It was like this idea like people view us as this kind of weird… to us, we’re not a failure because we never set ourselves up to kind of conform to the music businesses rules about what was a success. So, that kind of bugged me, that premise of “why would you carry on?” It's not that fucking hard. It's actually the opposite; it's really great. I'm paid to go off and travel with my friends and see beautiful places and eat nice food and swan around and meet friends. And sometimes no one comes to the show but we just consider the shows a vehicle for our social life essentially.

“It’s not really the question I was after,” Angio says. “It was the answer, the ways they’ve done that. Like any of us with anything we believe in and do, we’re so inside it that we don’t question it. What else would we do?”

Angio first approached Langford with the idea of the movie in 2007, then spoke with Langford and Timms, both of whom are now based in Chicago, his hometown. The Mekons had opened themselves up to documentarians before and had nothing come of it, so they were reluctant to give access to another. “Who would be interested?,” Langford wondered, and Timms was also unsure that the world needed another rock documentary, most of which she considered boring. Angio shared some of her concerns about rock documentaries and made certain promises to himself. He wouldn’t put a few stars and the start or finish of the movie to tell viewers why they should care, and he wouldn’t talk to fans after a show because they’re unlikely to do anything but gush. He also wanted to avoid the big picture problem that leads to those excesses.

“They’re too fannish,” he says. “They preach to the choir. I consciously made a film that wasn’t for the cult.” When making the movie, it helped that his editor knew nothing about the band and had no romantic attachments to songs. That gave her a clearer eye for when a song had been on screen or in the soundtrack for long enough, and nothing overstayed its welcome. In Revenge of The Mekons, that also translates to whole incarnations of the band being left out as the story is told from the long view rather than the album-to-album granular view.

That vision and his persistence won over Langford and Timms, whose hopes for the film were no higher than that it be entertaining. They took Angio’s proposal to the band, which agreed—“It had to be unanimous”—and told him that they’d be recording in England in two months’ time. That gave him a natural opportunity to shoot the band at work as well as time to talk to members who would otherwise be hard to track down as they’re scattered across the States, England, and Europe. He had yet to have a chance to line up financing, but he jumped in anyway.

At first, they asked Angio to give them a few days to themselves to sort out what they were doing before he came around with his camera, but the night before the sessions started, they went to the pub and decided it was weird to have him in the area waiting for them to invite him over and told him to come on. Filming a band while it was in the process of creating might seem like a way to add to the pressure, but Langford found the opposite to be true. “ I think we were so engrossed in what we were doing. We were working, so it was easy to shut him out,” he says. People did talk to him, though, and Langford found some of the things band members said revealing. “I’d never heard people talk about some things,” he says.

Still, during the sessions and later, some Mekons were less interested in being on screen than others. “People would run from the room [when he got the camera out],” Langford says. “You point a camera at people and they will behave completely weirdly. It’s hard to do that fly-on-the-wall, and Joe did it better than a lot of people. We actually let down our guard and felt comfortable with him on lots of occasions, but it’s still a very false situation.”

The story Angio tells in the film traces the band from its art school origins through its rebirth in the mid-1980s through the band’s time on Twin/Tone and A&M, more or less letting the narrative go around 1993 and I [Heart] Mekons. He had taken the band through the period that made its legend, and during which the band made music that gave fans a reason to believe that maybe there was a chance the music world would right itself enough to embrace The Mekons Rock ’n’ Roll and the anthemic “Memphis, Egypt.” He followed them through art projects including their collaboration with writer Kathy Acker, but he had to stop somewhere.

“At that point, I wanted to get across that they’d decided This is what the band is,” Angio says.

The Mekons Rock ’n’ Roll was the band’s first album on A&M Records—the label partially owned by Herb Alpert—and Langford says the band signed its contract in 1989 with a very clear goal. “We needed distribution and the guy who signed us said he was opening up major label distribution for indie bands,” he says. “We thought it was going to be something more stable and maybe a different business model to what we’d been going through before, but as history has shown us, that just collapsed. Major labels were not interested in a new business model, and they certainly were not interested in The Mekons. It was a nice idea for about 10 minutes, but we weren’t looking at pop stardom. We were looking at maybe being able to earn a sustainable living. Even that was beyond us.”

Although The Mekons had been resilient, the A&M deal falling apart left a mark. Nobody quit, but half of the band moved on, and for two or three years the band was Langford, Timms, Greenhalgh, violinist Susie Honeyman, and a rotating cast of bassists and drummers. Then in 1993, Honeyman left to have a baby. “It was really fragmented at that point,” Langford says.

Eventually the lineup stabilized with eight long-time Mekons—Rico Bell, Lu Edmonds (last in New Orleans playing guitar with Public Image Ltd. at Voodoo last October), Steve Goulding, and Sarah Corina in addition to Langford, Timms, Greenhalgh and Honeyman. “It’s been admirable that they’ve crafted their lives—even those with kids at home—around keeping this thing together,” Angio says. “Sally mentions at the very beginning somewhat facetiously but I think there’s some truth to it that success is the thing that kills bands in the end.”

Langford agrees. “The one consensus we have in the band is that we don’t really care about commercial success or money. It was obvious very early on that that was something that wasn’t going to be a big issue for us.”

About a year into shooting with a ton of footage, Angio finally began writing grant applications to pay to shape what he had into a movie. His previous film was on the filmmaker, musician, writer, and cultural provocateur Melvin Van Peebles (best known for Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song). Angio hadn’t thought about any relationship between How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It) and The Mekons project until he ran across this quote from the Chicago Tribune’s Greg Kot:

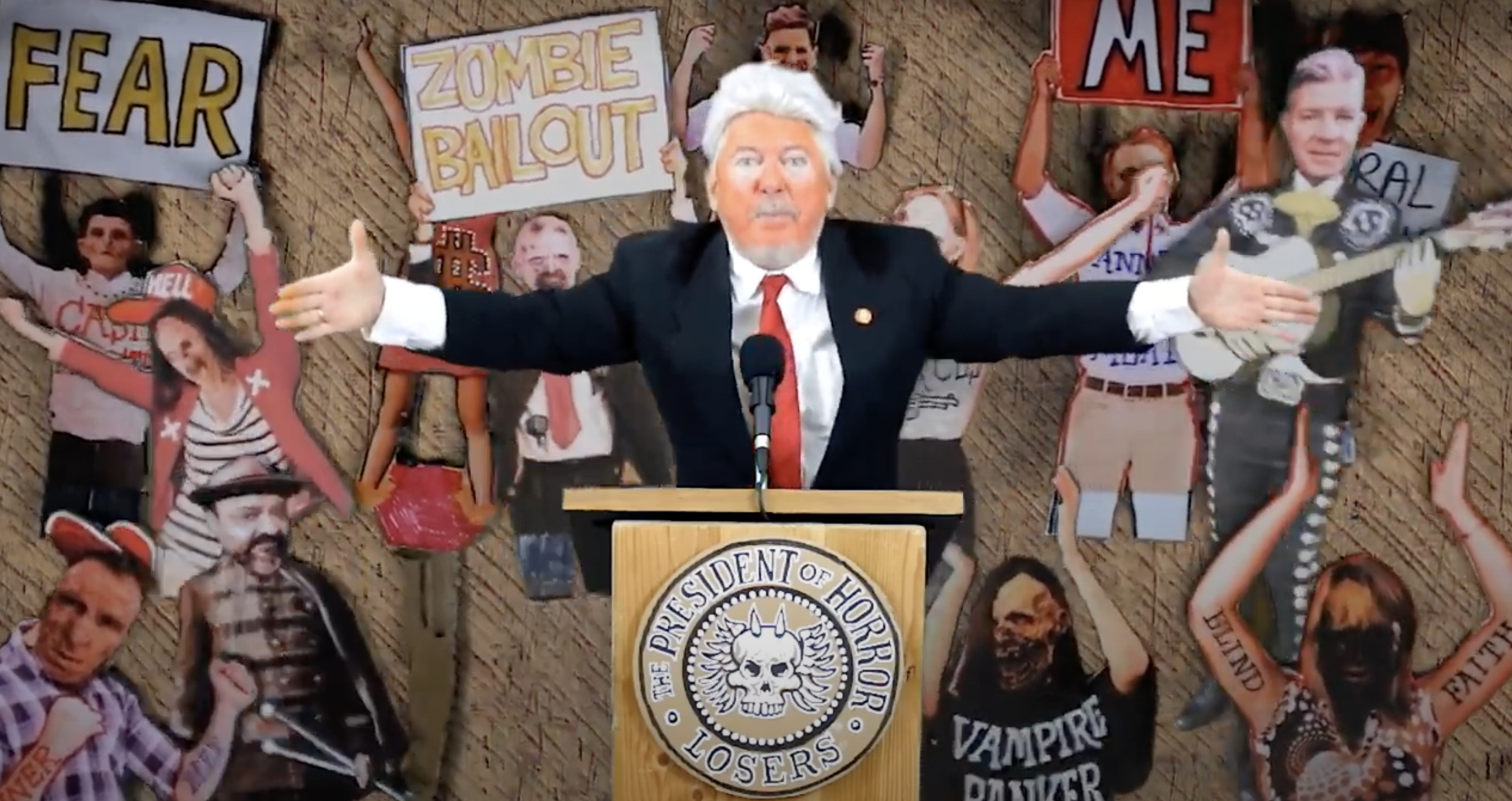

The Mekons have continued to put out records of bewildering variety, erratic musical quality and enormous heart. These function almost without exception as critiques of power and the abuse of power—whether in government, the record industry, or, less frequently, the bedroom.

“It was like, Oh my god, the same sentence could be used to describe Melvin Van Peebles,” Angio says. “The Mekons are the white, British, eight-person version of Melvin Van Peebles.”

Shooting Revenge of The Mekons was a way for Angio to fine tune his understanding of punk rock. The time was formative for him, not changing the way he thought as much as injecting whole new social and political viewpoints into his brain. Telling The Mekons’ story was a way to sift back through that era in his head to better appreciate what punk really meant.

“They couldn’t be further from punk rock as music, but they have kept those values,” he says. “Those have been very important to them.”