The Grammys and all Those Cellos

Why do the Grammys think every song needs strings?

The Grammys are often dismissed as behind the times, and some of it is inescapable. All voting members vote in the marquee categories, so engineers, producers, liner note writers, album designers, members of the classical music wing, and everybody else who’s a member of NARAS gets a vote on Album of the Year, Song of the Year, Artist of the Year, and so on. That’s almost inevitably going to skew results toward the well-known and the well-made. I read a convincing analysis on Facebook Monday night that Kendrick Lamar and The Weeknd split the R&B and hip-hop vote for Album of the Year, while Alabama Shakes and Chris Singleton split the roots vote, leaving the lane clear for Taylor Swift and 1989, but I doubt the dynamics were that complicated. 1989 passed five million albums sold last September, and since it had been around since 2014—a fluke of the Grammys’ weird eligibility calendar—it had stood the test of time that many people without vested interests in the results like to validate.

The place where Grammys really show their age is in the way songs are rejiggered for the broadcast, clinging to antiquated ideas about “good music.” Little Big Town was given the gift of cellos for “Girl Crush,” which added a heavy dose of unironic self-importance to a song that needs to be heard with some nuance. Tori Kelly and James Bay performed their songs “Hollow” and “Let It Go” respectively as a duet with only their two guitars, and the result was a rolling ball of earnestness in search of subtlety and form. The addition of a second voice and guitar took the delicacy out of Bay's song and the lightness out of Kelly's. The Weeknd’s “In the Night” was given an orchestral treatment that stripped out much of the song’s rhythmic snap as well as the obvious Michael Jackson reference that colors how I hear the track. As a result, the song itself was conventional.

“In the Night” did, however, confirm that Abel Tesfaye can sing, and that seems to be the old-fashioned gravitational lodestone that the Grammys keep coming back to. The broadcast is rarely about the song or the recording as much as it’s about evidence that the musicians it celebrates are really musicians. That was particularly obvious when Jack Ü’s performance of “Where Are Ü Now” put an electric guitar on Skrillex and gave Diplo drums. It too got the obligatory Grammy strings, which remain signifiers of class and taste, no matter how ineffectually they’re employed.

The emphasis on strings and stripped-down performances meant that much of the first hour of the Grammy broadcast passed with a restless languor as singers vocally mauled their own songs in an effort to create some intensity. Jackson Browne and The remaining Eagles—bless their cooling, harmonically gifted hearts—simply got up their and sang “Take It Easy” as a tribute to Glenn Frey. I’ll argue that it was pretty stiff in the knees, but that may be a trick of the mind caused by watching Don Henley drum like his arms are in casts.

Ironically, when someone actually had energy, the Grammys stepped all over it. The token hard rock performance by The Hollywood Vampires felt forced from its name, which came from a 1970s L.A. drinking society Cooper was a part of along with Keith Moon, Ringo Starr, Micky Dolenz and Harry Nilsson. Here it described the sober Cooper, the sober Perry, the who-knows-his-state Johnny Depp, and a few former Guns ’N Roses. Instead of giving the band a little pyro to spice up their song, the Grammys touched off a forest fire behind them.

Similarly, love or hate Pitbull, but he and his own girl army are not boring. So for some reason, the Grammys created a giant yellow and black construction site grid behind him, saddled him with a second set that he had to inhabit, and sent out Sofia Vergara in a boxy taxi costume—perhaps the only thing that could make her look silly. All of that made him look small and busy when his best thing is standing in one place and feeling the Latin-inflected eurodisco ecstatically while the party—really, just women—cycle around him.

In all of those cases, the Grammys didn’t seem to trust the artists and their music. The best moments put aside the show biz and someone else’s notion of art and let the musicians do their work. The Alabama Shakes didn’t need any help, nor did the army of blues guitarists paying tribute to B.B. King. Stevie Wonder and Pentatonix didn’t suck, though their tribute to Earth, Wind and Fire’s Maurice White seemed dashed off. How do we pay tribute to him in a show that already includes a forest fire? How about a cappella?

For me, Lady Gaga’s tribute to David Bowie didn’t work, but it wasn’t a failure of nerve on anyone’s part. Since her career has been a prolonged effort at Bowie-inspired identity (re)construction, Gaga was the right person for the job. Unfortunately, there was so much going on that I couldn’t find a through-line as she hurried from song to song as if she was trying to squeeze in Bowie’s entire ‘70s catalog into her allotted six or so minutes. I later wondered if there was a visual gimmick in each of the songs she at least touched on, and if that gimmick highlighted the way Bowie changed identities from album to album. If that was the case, it didn’t work because the medley’s brisk pace prevented any idea from registering as anything more than just another distraction. I admired Gaga’s eccentric choice to sing Bowie’s songs at the bottom of her range, but it came off like much of the medley as simply odd.

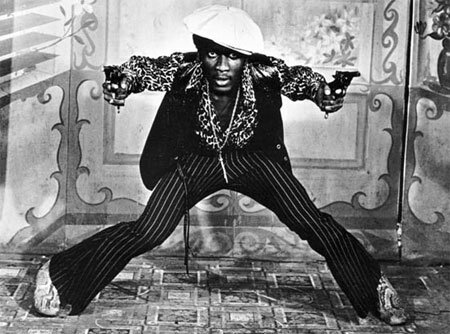

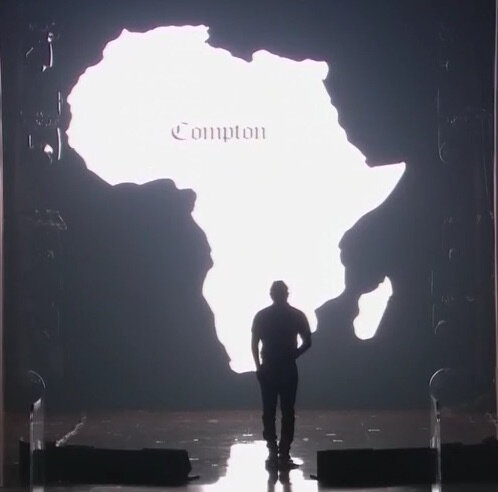

As Carl Wilson wrote at Slate, hip-hop won the Grammys with the performances from Hamilton and Kendrick Lamar. The production threatened to overwhelm Lamar, but his own intensity kept the focus on him, whether he was on the Jailhouse Rock set or on an overpopulated stage. Lamar played my two favorite shows of 2015, and as Monday night confirmed, he is also compelling television. His set and Hamilton also felt like successes because they excelled in ways that the Grammy powers-that-be seem to understand. Hamilton presented hip-hop as art, and Lamar made his musicality inescapable. The precision and rhythmic complexity of his final number was as dazzling a musical feat as the moment was confrontational.

The Grammys trumpet the broadcast’s “Grammy Moments.” After the last handful of years, I take that phrase to be code for “moment when the Grammys handicap the artists.” The question the night raised is why the Grammys don’t trust the artists and their music. And what’s with all the cellos?