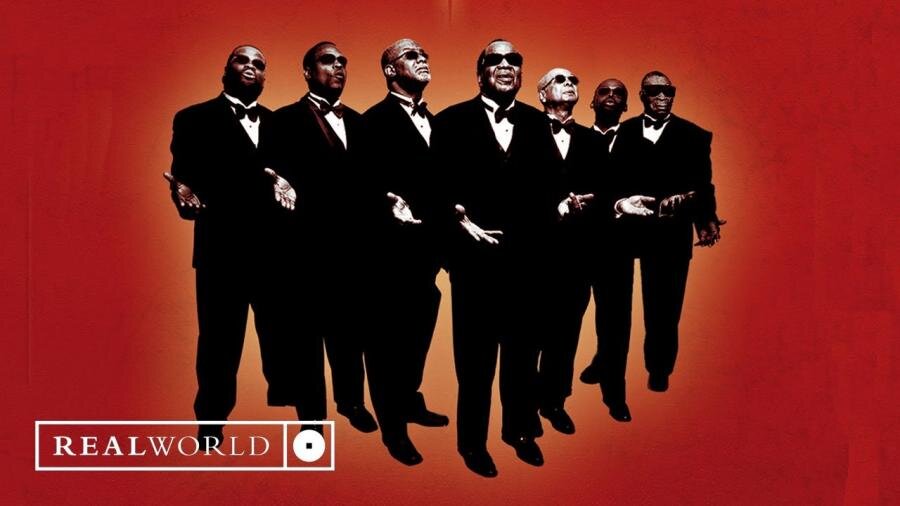

The Blind Boys Branch Out for Christmas

Producer John Chelew helped the gospel legends get unexpected performances out of them and their guests on their Christmas album.

(Earlier this month, I talked to producer John Chelew about his experiences working with The Blind Boys of Alabama on their 2003 Christmas album, Go Tell it On the Mountain, which was recently reissued. On Monday when I sat down to start writing this story, I discovered on Facebook that he peacefully passed away at his home in New Orleans on Saturday night, apparently from natural causes. He was generous with his time and memories for this story, and I’m glad to get an opportunity to draw attention to this one small part of a career that also involved albums by John Hiatt, Papa Mali, Ruthie Foster, Richard Thompson, Vic Chesnutt, Aaron Neville, Charlie Musselwhite, Paul Weller, Los Lobos, and many more.

I’ve written the story in present tense, which is the way I tend to do pieces like this. I tried to write it in the past tense to reflect Chelew’s passing, but it felt too weighty under the circumstances.)

“I guess the thinking was that the Blind Boys don’t know how to sing bad. If we pick the right material and match them with the right guests, it should be an interesting experiment and work out pretty good.”

Producer John Chelew is speculating as to why he was tapped to produce The Blind Boys of Alabama’s Christmas album Go Tell it On the Mountain in 2003. This holiday season, Omnivore Recordings reissued it, which was the third in a series of four albums that The Blind Boys of Alabama recorded for Peter Gabriel’s Real World label in England. Chelew credits Chris Goldsmith, the executive producer for all four albums for the idea of a Blind Boys Christmas album. The idea seems inevitable, but Go Tell it On the Mountain was their first Christmas album in more than 50 years together.

The commercial logic was unassailable. Every year, it’s going to be like a new album, Chelew remembers Goldsmith explaining. Since holiday recordings tend to have at least a four year lifespan, there was a clear truth to that. Since the idea was to pair the Blind Boys with musical guests on the tracks, Chelew was excited by the prospect of putting together such artists as Michael Franti, Solomon Burke, Mavis Staples and Shelby Lynne with the Blind Boys in a meaningful way.

“When you have guests, I like to see them interact authentically with the headliners,” Chelew says.

Often on albums that involve guest artists, the guests record their parts in studios convenient to them and send them digitally to the producer, who integrates them into the finished track. In most cases though, Chelew wanted the Blind Boys and the artists in the studio together. They flew to London to sing the British folk song “In the Bleak Midwinter” with Chrissie Hynde. On the track, “they were being a gospel choir for Chrissie Hynde until the outro, which goes on forever,” he recalls. “Then everybody’s ad libbing and doing their thing. It’s really beautiful.”

The experience was powerful for Chelew because he had admired Hynde’s voice for years. “I shudder when she sings,” he says. “You can hear the English thing, but you can also hear the Dusty in Memphis or Dionne Warwick in her voice.”

As he recalls the sessions for Go Tell it On the Mountain, Chelew the music fan is as present as his producer side. His admiration for many of the artists he worked with on the album is obvious, and when we talk about the importance of finding the right voice for a song, he detours to talk about his love of John Cale and his version of “Hallelujah.” He remembers Mavis Staples in the studio with the Blind Boys telling the story in the studio about how Bob Dylan asked her to marry him. She told him to ask Pops Staples, and when Dylan asked Pops, he said ask Mavis. It’s clear that having an eye and ear on that kind of music history isn’t lost on him.

The only track that kept the Blind Boys and the guest separate was the title song. They cut their vocals with the house band for the album—John Medeski, Duke Robillard, Danny Thompson, and Michael Jerome, who these days drums with Better Than Ezra—in Los Angeles, then Chelew went to a studio in Sausalito, California to record Tom Waits. He showed up with 30 to 40 rare gospel CDs, “just to get us in the mood and play us different ideas,” Chelew recalls. “It was like Professor Waits.”

The Blind Boys initially wanted to record the song in a major key, but Chelew disagreed. “I said Let’s do it in the minor, the bluesy way,” Chelew says. That’s how the song was done, and keys were similarly changed from major to minor on a number of tracks to “darken them” and give them greater emotional depth.

When Waits asked Chelew how he thought he should approach the vocal, Chelew thought he ought to whisper it like a lullaby.

No, I think I’ll preach it, Waits replied, and that’s the approach he went with that led to the keeper take. Afterwards, Chelew apologized to Waits for potentially steering him in the wrong direction, but Waits wouldn’t have it.

No, I needed someone to go up against. Thank you for saying something to do different.

Some tracks required more trust on the part of the Blind Boys than others. “The Christmas Song” is one of two secular songs on the album, and Chelew admits, “I don’t think Clarence Fountain would have done it when we first worked together in 2001,” but by their third album working together, he was able to go with Chelew on the duet with Shelby Lynne.

More challenging was “Away in a Manger,” which had two obstacles. First, Fountain and Jimmy Carter—two of the three remaining Blind Boys of Alabama at the time of the recording—thought the melody was too sing-song to bother with, and recasting it as a blues with Robert Randolph didn’t help much. Guest vocalist George Clinton was the other. “George Clinton had a very different lifestyle from the Blind Boys, obviously,” Chelew says. He had a drug addiction problem, so some wondered if it was sacrilegious to sing sacred songs with him. George Scott, the third original Blind Boy, took the lead vocal and sang with Clinton, who had four baffle walls around him in the studio so that nobody had to see what he was up to.

Clinton and Carter took 12 or so passes each on the song, and Clinton performed a number of takes very differently. Chelew assumed he was trying out different approaches, but once they were done, Clinton explained that he heard them as complementary parts and wanted to use them all. “We ended up blending all of them together in the final mix,” Chelew says.

Solomon Burke joined the Blind Boys for “I Pray on Christmas,” a Harry Connick Jr. song that made Chelew think of them when he heard it while driving one holiday season. “We blues’d it up,” he says.

The session for the song fell on a Sunday, and Burke brought what seemed to be an entourage from church. He also brought fried chicken for lunch and fed everybody. Burke came with a song that he had in mind and was prepared to perform, and he had never heard Connick’s song before. Chelew played it for him a couple of times, and then Burke went into the studio to sing. “He did one take completely and that was it,” Chelew recalls. He instinctively asked him for another take, but Burke announced, Gentlemen, I think you have your track.

Chelew recorded Aaron Neville and the Blind Boys’ a cappella version of “Joy to the World” at Piety Street Studios, and he got Neville at his most natural. “It was bare bones Aaron without all the flourishes and notes that were held extra-long,” Chelew says. It’s an Aaron Neville rarely heard these days on record, and he got it by getting to work without a lot of fanfare. Days later after Chelew had returned to Los Angeles, where he lived at the time, Neville called to say that he knew what they were looking for and he was ready. Chelew passed on the opportunity to record him again.

“I think he would have decorated it and over-sung,” Chelew says. It’s something he’d seen many singers do over the years, and those experiences made him look for ways to capture spontaneous, unpre-meditated musical choices.

“You hope the the tape machine or ProTools are running when they’re soundchecking,” he says. “First thought, best thought. When you think about it too much, you’re not going to get it.”