The Best on Bowie

Given a little time, writers and critics brought some interesting takes to David Bowie's passing.

[Updated] When I suggested yesterday that many critics and journalists felt David Bowie’s death too strongly to jump in with their strongest stuff right away, it looks like there was something to that. Later Monday and on Tuesday, stronger pieces started to show up, and speaking personally, my own game got a little better. I wish I’d have talked about Bowie as the gateway artist he was, because although Lou Reed and Iggy Pop are as important to me as Bowie, Bowie’s musical accessibility meant he was the first of the three that I listened to and connected to. I wouldn’t have got to the New York Dolls or punk rock had I not gone through Bowie first, and conversations with friends make me think I’m not alone there.

I also couldn’t find an elegant way to theorize that Let’s Dance was a hit because the pop marketplace was so flooded with Bowie knockoffs that their brains fell out when they had the real deal. The actual music on the album obviously had something to do with it, but so did a new wave full of singers who appropriated his vocal mannerisms, fashion sense or sound. The New Romantics at London’s Blitz Club copped to it, but they were hardly alone.

If you still have an appetite for retrospective Bowie writing, a great place to start is Carl Wilson’s piece for Slate, which emphasized Bowie’s relationship with his fans.

Countless pop stars this week are talking about how the phases of Bowie’s self-inventions inspired them, and justly so: Each of his incarnations birthed movements and subcultures. But in my heart his greatest acolytes were the unknown thousands who recognized him as their enabler, their transformer. Bowie sang for the as-yet nonexistent ones, for the awkward, the strivers. He sang for the members of the public who were full-feathered birds of paradise in their own imaginations yet might also struggle through a simple visit to the grocery store. Bowie’s celebrity was part of his medium, but his core was about ordinariness, the kind of “superstardom” produced in the early Warhol Factory, pre–Studio 54: a vision of existence as ugly as it was glorious, extraordinary but also always below average. Until Sunday night, Bowie and John Waters felt like two of the last surviving links in that particular chain.

Chris O’Leary dissected one of my favorite Bowie tracks, “Sound and Vision,” also for Slate:

Though it’s a depressive’s song, “Sound and Vision” is shot through with little moments of joy, like the way Davis’ drum fills sound like a string of firecrackers. Bowie’s opening phrase, a slow, sleepy rise over an octave (“don’t-you-won-der sometiiii-ii-ii-ii-mes”), seems as if he’s been listening along and just started singing, carried away by what he’d set in motion. There’s a wonderful precision to Bowie’s vocal, a sense that he has to plot his course exactly, underscoring his happy flights of fancy (the long-held ooooos) with glum, nearly-spoken phrases (“nothing to do, nothing to say”).

The first paragraph of her reflection on Bowie’s death that Lindsay Zoladz wrote for Vulture helped me get back on track with its emphasis on the personal:

I don’t think we fully realize what an intimate connection we have to the musicians we love until we lose them. My Bowie grief feels at once collective and also incredibly private, impossible to explain. The obituaries are trickling in; here come the heated debates about the best Bowie record and whether or not he was better than the Beatles or the Stones or both of them combined. I’m not ready for that today. I’m not even ready to confront the full contours of his voice in the harsh intimacy of my headphones. The best I can do is put on “Heroes” in the other room and let it drift over to where I sit, like a muffled dream.

Mary Elizabeth Williams wrote about how he played with style and sexuality for Salon:

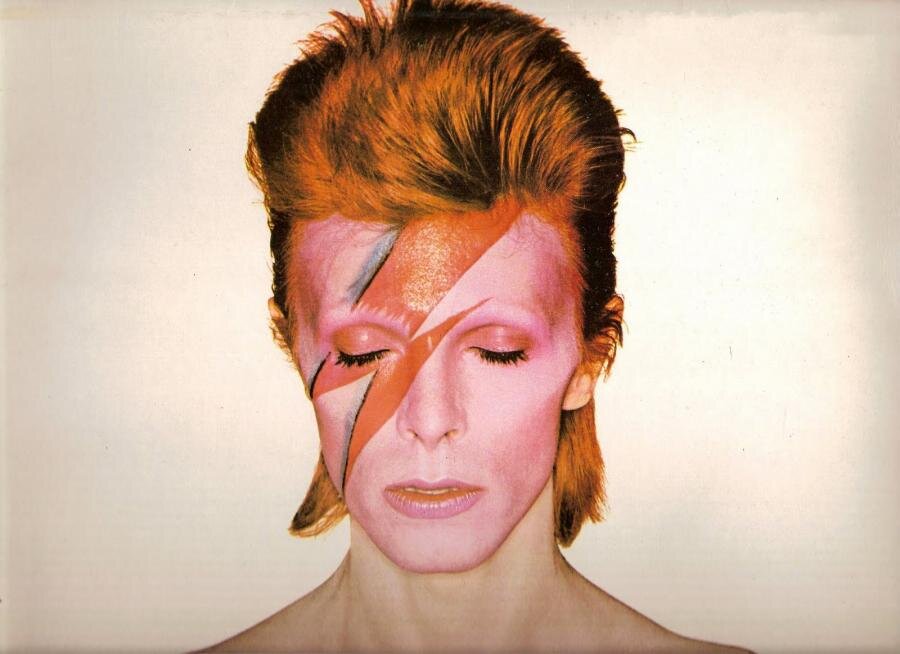

Bowie launched his career as part of a generation of early-Seventies artists like Marc Bolan and Lou Reed and the New York Dolls, all tweaking the traditionally hyper-masculine world of rock and roll with a brazenly feminine glamour. And he did it in a way that was simultaneously post-sexual and incredibly sexy. He was a space alien with two different colored eyes, far beyond the confining limits of male and female. He sang of rebels who made mothers unsure “if you’re a boy or a girl.” He laughed off what it means “when you’re a boy” — including having other boys check you out. When he wore men’s suits, he looked as elegant as Marlene Dietrich in them. He was also, Christ, so goddamn hot.

Sally Kohn examined his queer legacy for Refinery 29:

Let’s face it, David Bowie might have been the world’s first transgender ally — before we had words like “transgender” or even “ally” in our vernacular. He was also one of the first famous gay allies. Bowie “came out” as gay in a 1972 interview long before the likes of Freddie Mercury or Elton John had even hinted at coming out of the closet. Later, Bowie said he was bisexual — in 1970 he married his first wife, a model named Angie, after they met because they were sleeping with the same man. Much later, Bowie said that saying he was bisexual was “the biggest mistake I ever made” because he didn’t feel like a “real bisexual.” “I’ve always been a closet heterosexual,” Bowie said. But even in his own searching, Bowie was illustrating a fluidity of sexuality that many still have trouble grasping.

Finally, Bob Boilen of NPR’s “All Songs Considered” interviewed producer Tony Visconti and saxophone player Donnie McCaslin about the making of Blackstar for a piece that was first posted December 17. In it, Visconti and McCaslin never let on that the album was anything more than another Bowie album, and if Boilen knew, he didn’t let on as he airily hoped to hear the music from the album performed live. That in and of itself is fascinating to listen to now, but the interview is very much about Bowie’s musical process on the album, and while so much writing about Bowie right now takes the macro view, it’s nice to hear something specific about Bowie the musician.

Tony Visconti: "He had one key jazz player in his band for well over a decade, maybe two decades and that was Mike Garson, who is a very accomplished jazz pianist. And so, he always had a hint of jazz in sort of the earlier things. And David has a remarkable knowledge of jazz chords. I don't think he quite knows what they're called. I mean, I don't even know what they're called, but they have things like 13th in them and flatted 9ths and all that. And you don't hear that in an average rock song. But they were well hidden in the recordings of the past. Or alluded to."

Updated 11:04 p.m.

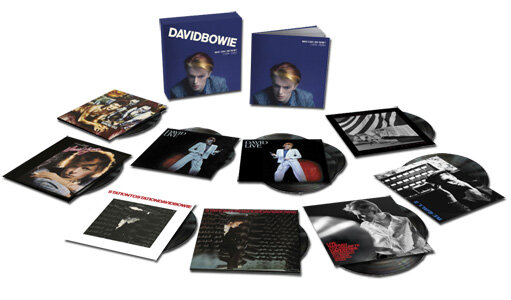

When I posted this story, I intended to include Michael Toland's review of Blackstar:

Produced by classic Bowie cohort Tony Visconti and recorded with a group of NYC jazz musicians, Blackstar builds its palace on groove. Drummer Mark Guiliana and bassist Tim LeFebvre snake through each cut with little reliance on straight rock beats, setting up rhythmic beds over which Bowie can overlay sensual melodies and idiosyncratic lyrics. Woodwinds master Donny McCaslin and guitarist Ben Monder insinuate themselves into the arrangements with long, legato lines, while keyboardist Jason Linder provides the glue to which it all sticks.

Singing over the songs as much as with them, Bowie lets the flow lead him down the stairs, around the corner, and into the woods. The grooves lift him up even when the subject matter threatens to drag him back down. And make no mistake, hints of death abound.

Writer Greg Tate is almost always a must-read, and his examination of Bowie's relationship to the Black community is no exception:

Like anybody in the lily-white rock world of yon who sang, danced, and played saxophone, Bowie was beyond indebted to black culture. But much akin to Miles Davis, assimilating influences for Bowie meant he’d granted himself license to warp and mutilate those sweet inspirations in pursuit of self-renovation. This trait is abundantly evident on 1975’s Young Americans album. Bowie’s rapprochement with Philly Soul in Philly International’s home base, Sigma Sound, remains a watershed moment for our still-racialized world of American music-making. YA marked Bowie’s maiden voyage with Puerto Rican–born Apollo pit band guitarist Carlos Alomar, who’d become a studio and touring mainstay for the next decade.

Updated January 14, 10:44 a.m.

When the story was first posted, the Salon excerpt wasn't the one intended. That has been corrected.