David Bowie Made Being a Rock Star Pay Off

David Bowie made the most of the permission granted him as a rock star.

I”m late to the Lamenting Bowie party because my mind isn’t percolating with insights I want to share. I sleepwalked through much of yesterday, returning again and again to nothing wiser than He died. I haven’t cared a lot about Bowie in the last decade, but he was still in the world and still full of possibility. More than many of his peers, he'd left behind a musical trail that gave me reason to believe he could still do something amazing, even if it had been a while since he had. His ‘90s albums seemed to take inspiration from those inspired by him, or they felt forced—reinvention through muscle rather than insight. The idea of being part of a musical democracy in Tin Machine was laudable, but it was impossible to accept the rest of the band as his equals because they only were if he allowed them to be.

But Bowie was a great rock star—one of people who made it a thing to be. Stardom didn’t just unlock medicine chests, liquor cabinets and boudoir doors for him; it gave him permission to take chances—sublime, batty, and otherwise. He was indulgent, but his indulgences paid off in his exploration of Japanese avant-garde fashion, productions of Lou Reed, The Stooges, and Mott the Hoople, and a tour as Iggy Pop’s piano player. He acted with Nicholas Roeg. When he went down a drug hole, he came out with Station to Station, which has an album’s worth of catchy parts in the title track alone.

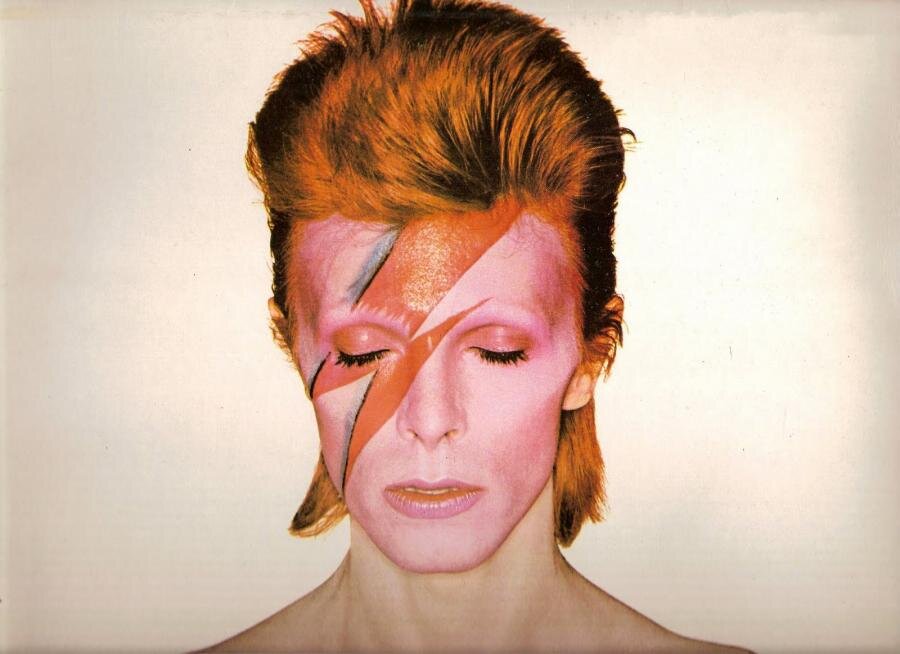

I’ve long argued that Bowie’s characters were the tail wagging the dog. For me, they represented a way to pull songs together more than they were actual characters, and that it’s hard to hear on the albums how Aladdin Sane is a different person from Ziggy Stardust. Earlier this year, I reviewed the Five Years 1969 – 1973 box set, which illustrated what I consider “the power of positive posing”:

Last year’s Bowie retrospective “David Bowie Is” show at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art provided some insight into this period. One room documented the efforts of a pre-“Space Oddity” Bowie to become somebody. In one audio clip, he spoke of how he would buy certain albums—usually jazz ones—not because he wanted them but because he wanted to be seen as the sort of person who did. Similarly, he would walk around with a paperback carefully positioned in his jacket pocket so that people could see the title of the book. He didn’t necessarily read the book, but he wanted to be seen as the guy who would.

As superficial as that sounds, that experience clearly prepared young David Jones to become David Bowie. You could say he was being a pretentious git, or you could say he was being a teenager, doing something primarily for effect. At the same time, he was learning—or perhaps honing—his ability to inhabit someone not entirely himself.

By Young Americans and Station to Station, the character concept had run aground. Even if it was an extraneous bit of sideshow, it was sideshow that suggested that rock could be about something. Today it’s hard to remember how controversial he was for much of the ‘70s, and how his refusal to stand still kept his relationship with his audience from ever being simple. He played with gender when the mainstream wasn’t sure what to do with a flamboyant dude who flirted with homosexuality, then embraced R&B music to the outrage of fans who liked their glam rock pale and powered by Marshalls. Young Americans packed the additional whammy of alarming the Authenticity Police who were upset at a white British guy trying on soul. Then when people caught up to that, he stopped writing full-fledged songs, populating Side A of Low with fragments that seemingly came from a sonic nowhere, and Side B with ambient tracks that erased the horizon lines.

Somewhere around “Heroes” or 1979’s Lodger, either Bowie stopped scurrying away from his audience, or perhaps after all the changes he’d put them through in less than a decade, they stopped being rattled by his refusal to hold still. He had become sufficiently accepted to appear on Bing Crosby’s Christmas special in 1977 to sing “Little Drummer Boy,” and he appeared on Saturday Night Live in 1979 after the release of Lodger. 1980’s Scary Monsters (and Super-Creeps) was his first album after Ziggy Stardust and the Spider from Mars to go platinum on the strength of the singles “Ashes to Ashes” and “Fashion,” and he followed it with Let’s Dance in 1983. It was the moment when he and the marketplace were in perfect sync and served as a belated victory lap for the ‘70s.

Throughout all that, Bowie’s provocations mattered because he worked in the popular arena. He wasn’t the first to dramatize gender, sexuality and race-related themes, nor was he the first to draw attention to the tensions around around authenticity. Others before him had asked hard questions about the fundamental nature of pop music, but many of those other pioneers plowed their fields less publicly, or with less on the line. Each time Bowie challenged his audience, there was a substantial one to lose.

As a fan, part of the beauty of The Next Day and Blackstar is that in his last years, Bowie sounded like he was charting his own course again. It’s also reassuring to know that because he stage-managed his own musical exit, the odds are low that we will have to listen to final tapes of him performing in a diminished state. Because if he left behind his version of Johnny Cash’s American Recordings, we’d have to listen.

I spent part of yesterday reading what people wrote about Bowie, and felt like most people were in my shoes—too stunned to be stunning. I also wondered what Iggy thought. Iggy, Lou Reed and Bowie opened the door to a world of music outside AM radio and meatheaded hard rock for me as they did for so many others. Since I didn’t see nor expect any tweets or remembrances from Iggy yesterday, I looked back at I Need More—the collection of autobiographical stories he published shortly after working with Bowie on The Idiot. Most of the book is about his Stooges days, but Iggy tells this story about being in recovery in a studio in France with Bowie taking a break to play ping-pong. I like this story for Bowie’s generosity and the playful side we rarely saw. The ping-pong side.

Never in my life had I been able to play ping-pong. Never had the coordination—literally, couldn’t play.

David said, “Come on, give me a game.”

“I can’t. I can’t play.”

But I tried it, and suddenly that day I could play, and I’m playing and we were tied and I said, “You know, man, this is weird. Really weird. I always failed at this game, and now I can play it.”

He said, “Well, Jim, it’s probably because you’re feeling better about yourself.” In the most gentlest way he said that, because usually, you know, nobody wants to be anybody’s teacher or learner. You know what I mean? In the very gentlest way he said that. I just thought that was a nice answer. Three games later, I beat him and he never played me again. I got good real fast.