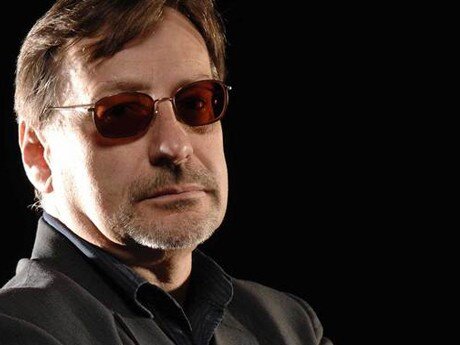

Southside Johnny Brings a Little Barroom to Every Gig, Even Jazz Fest

The last man standing in the New Jersey R&B band still applies the lessons he learned playing bars on the Jersey Shore.

For Bruce Springsteen, being a bar band was a starting point; for Southside Johnny Lyons, it was a destination. Since well before the release of 1976’s I Don’t Want to Go Home by Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes, Southside Johnny has been working clubs the old school way, with the passion, sweat, and belief that the next few hours might be all we get, so we’ve got to live them now. That’s the approach he brought to New Jersey boardwalk dives, and it’s the one he has used to make larger venues around the world feel smaller and funkier for decades since.

Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes will play Jazz Fest’s Blues Tent at 5:35 p.m., and while his musical journey has been very different from Springsteen’s, their stories are tightly linked. They played the same bars at the same time coming up, and the name Southside Johnny echoed those of characters that turned in songs on Springsteen’s Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ. Springsteen’s label, Columbia, signed Southside Johnny as well and released I Don’t Want to Go Home months after Born to Run made New Jersey and all things Springsteen marketable. When Springsteen became embroiled in a lawsuit with his then-manager Mike Appel, he couldn’t record and Southside’s This Time It’s for Real was the only new release to scratch what at the time was referred to as “The Jersey Sound” itch.

The connection between the two acts was furthered by Miami Steve Van Zandt sharing duties in the E Street Band and as an Asbury Juke, and songs by Springsteen on the Southside Johnny albums. Springsteen contributed two songs to the debut album including “The Fever,” two to This Time It’s for Real, and three to Hearts of Stone, one co-written with Lyons and Van Zandt.

In 2010, The Promise compiled the songs Springsteen wrote and discarded as he felt his musical way from Born to Run to Darkness on the Edge of Town. Patti Smith’s “Because the Night” came from that period, as did “Fire,” which became a hit for The Pointer Sisters.

“I thought he was insane,” Lyons remembers when Springsteen offered him “The Fever.” He and Van Zandt were rehearsing the horn section before going in the studio to record I Don’t Want to Go Home at The Stone Pony, the famed Asbury Park club, when Springsteen came in and played “The Fever” on piano. Lyon had seen Springsteen play it with his band a few weeks earlier and thought it was a hit, so when Springsteen offered it to him, he thought the offer was too generous. Doesn’t fit on my album, Springsteen said. “He wanted Darkness to be Darkness, and he didn’t think the song fit on that. I said O-kay.”

The debut album includes “How Come You Treat Me So Bad,” which Southside recorded as a duet with New Orleans’ Lee Dorsey. When Van Zandt wrote the song, he heard it as a tribute to Allen Toussaint, and when a friend at the label suggested that they reach out to Dorsey, they jumped at the chance.

“Lee was a great guy, “ Lyons remembers. “A real open-hearted, decent human being. Lee came up in a three-piece suit with a hat. He looked magnificent.” Lyons and Van Zandt took him to a hotel in Manhattan near where the band was recording, then went back to the studio to get back to work. That night, Southside got worried that he might be lonely and called Dorsey’s room. When he got no answer, he started to worry that maybe Dorsey had been mugged. He tried again an hour later with no luck. The next morning, he went to pick Dorsey up expecting the worst, but Dorsey was in another three-piece suit with a bottle of Chivas Regal. When asked where he was last night, Dorsey said, Oh, I went out with Ben E. King. “He came to the studio and knocked it out in 20 minutes, then he sat around and told stories.”

These days, Southside is the only member of the band who goes back far enough to remember those stories. There have been more than 150 Jukes by his count, which includes Jukes-For-a-Day like Springsteen and Jon Bon Jovi, who have sat in on occasion. He figures that if players will do their homework, they can play the gig, but the willingness to work isn’t the bottom line.

“They have to be Jukes,” Lyons says. “You have to have a sense of humor, you have to be able to put it out every night, and you have to be able to hit the curveball. If I start doing a song that you don’t know, play.”

Those are lessons he learned playing bars over the years. Basic truths still hold. “You’ve got to work hard,” he says. “You’ve got to show you’re enthusiastic about it, and you really can’t fake it. You have to read a crowd. What do they want? If they want to rock, you rock. If they want to cool down, you cool down. I can dictate terms on that, but I have to be aware that there’s a rhythm to the night that’s partly controlled by the audience.

“And if you screw up on stage, you go to ‘I Don’t Want to Go Home’ or ‘Talk to Me’ and everything’s redeemed.”