Social Distancing Sends Musicians to Live Streaming

As a response to social distancing, musicians are playing live stream concerts from home to entertain us and help cover their expenses. But is it working?

From a cozy nook in her Southern California home, Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Melissa Etheridge played her acoustic guitar while her wife recorded her. Etheridge was there to entertain, and also to soothe. She took a moment between songs to remind her digital audience to find love and tranquility amidst the doomsday moment we’re living in.

“Love yourself and take that love and love others,” Etheridge consoled. She reminded us to breathe, that “this is something we’re all going through together.” Her tone was reassuring; her demeanor optimistic; her music, a remedy.

Etheridge had an audience, but it was invisible and included people looking in from all over the world. Now that we’re indefinitely shut-in at home, we’re increasingly hungry for outside entertainment. As life turns inward and becomes constrained within four walls, we’re experiencing a mass craving for escapism in the form of the arts.

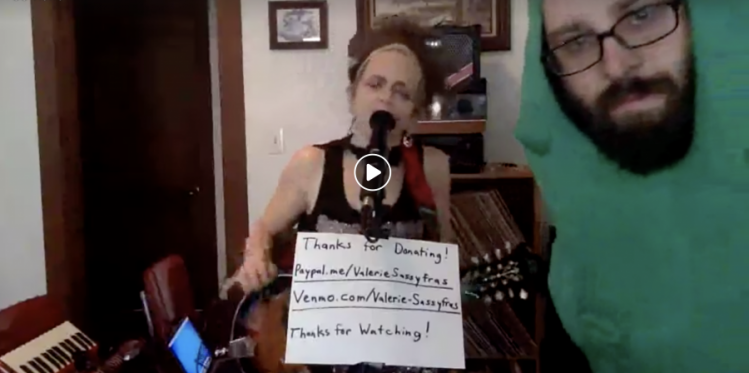

At the same time, musicians have bills to pay and time on their hands. Now that many are experiencing drastic cuts to their earnings due to tour cancellations and the shut down of music venues, they’re pivoting from live gigs to live streams, Venmo usernames attached. For musicians, it’s a way to cope, connect with audiences, and for many, compensate for devastating losses of income.

Melissa Etheridge live-streamed her intimate show on the newly-birthed platform, Sofa King Fest (SKF). New Orleans tech entrepreneur Travis Laurendine launched the Internet-based festival as an emergency response to the situation. The festival, Laurendine says, “is a conduit for helping people to stay at home and be entertained and to help musicians get paid for doing it.” SKF is a space for musicians from around the country to showcase their work and raise money for themselves, their crew, and the beneficiaries of their choice. Artists who want to participate can request a time slot by filling out the form on the website’s homepage.

Laurendine is optimistic that this crisis can be an impetus for innovation and give musicians from New Orleans and elsewhere new tools to grow their audiences and learn how to sustain a career beyond live gigs. “It could end up being this blessing in disguise,” he says. “That we could end up having something more interconnected, musicians have more discoverability, and we get all these new entertainment experiences.” He’s hopeful that the explosion of live-streaming can give musicians another layer of resilience. They'll have to quickly learn how to differentiate themselves, he believes, and hopes that artists can create one-to-one relationships with their fan bases via intimate live streams, and from that, gain lifetime customers.

Many musicians, like Etheridge, have taken to live-streaming not just to raise money and fill empty time, but to engage in collective therapy with their audiences. “Sofa King Fest is musical therapy for the whole country in this time of need,” Laurendine said. On a live-stream show today, COVID-19 isn’t just the elephant in the room. It’s the reason for the season. Acoustic guitarists suddenly become therapists as they gently soothe the nerves of a universally tense, nervous, and physically distant audience. Musicians are taking on the role of healers.

Sofa King Fest is just one of many platforms working to bring musicians and audiences together. Twitch streams live concerts and DJ sets among other things, and emerging platforms can take clues from existing projects like StageIt, an online venue for live concerts. SKF isn’t the first or only live-streaming platform, but by emerging in response to the Coronavirus crisis, it is specifically tuned into the moment. Its has emerged to help indie artists find an audience and to organize the experience with a festival-like schedule.

Another DIY response to help musicians perform has come through the Facebook page, “Viral Music--Because Kindness is Contagious.” The group serves independent musicians and bands who have lost their livelihoods due to social distancing. They are using the group to upload and advertise their live stream shows. Group founder Candace Oxendale Fowler started it as a coping mechanism. Fowler and her husband see between 150 and 200 shows and year and host a house concert series in Atlanta called “Red Boots Roots.” She got the idea to launch the platform with the hope that it would “replace some of the income [musicians] are losing while not touring and playing club gigs." In addition to generating income for musicians in need, she wanted to create a virtual community to fill the gap of live music while everyone stays at home.

“Connecting artists and fans seemed like a decent place to start,” Fowler says, “but I never expected the Facebook group to explode the way it has.” She created "Viral Music" on March 14, and it now has nearly 30,000 members.

This moment presents an opportunity to rethink the artist-audience relationship we take for granted. Instead of paying a cover to an anonymous bouncer or throwing a buck in the tip jar, digital viewers are now handing funds directly to artists’ Venmo and Paypal accounts. And instead of waiting in line and packing shoulder-to-shoulder into a sweaty, booze-dripping club to see one good set, fans watch their favorite artists perform from their couch.

So far, live stream platforms seem more advantageous for some artists than others. Acoustic acts seem to do well. Folk and Americana seems at home on the intimate live-stream; musicians who once played from several meters away atop the stage are now serenading you just inches away on your personal screen, and their music is based on the relatively unmediated communication between the performer and audience.

Younger bands well-versed in social media seem to have an upperhand, too. Millennial artists who have already built digitally comfortable fan bases are positioned well to continue expanding upon that base. In theory, the digital universe should also come more naturally to electronic acts than to those whose performance relies on compelling visual or theatrical elements.

At the moment though, Baton Rouge musician Alex Cook says he has some doubts about the effectiveness of live streaming. Cook, a singer-songwriter and guitarist for The Rakers and the solo project Museumgoer, isn’t sure that audiences are sold on live stream shows. “I think right now we’re in a charmed phase of it,” he says. Eventually, he thinks, people are going to get tired of watching someone play guitar from their couch. “After a few weeks of watching people fumble with their phones, people are gonna want to see more high-quality content.”

One of the challenges with this phase, he believes, is the platform. “The nature of [Facebook and Instagram] is you’re not gonna sit there and watch something for an extended period of time,” Cook says. We’re conditioned to scroll, look for a few seconds, and then move onto something else. This will make it challenging for artists to grab ahold of viewers’ attention spans, when they’re already in a space where a million things are vying for their attention at once. Sofa King Fest tries to address this by creating a separate space dedicated solely to live-stream shows, where audiences don’t have any established counterproductive behaviors.