Sasha Masakowski Finds her Music in a Mass of Wires and Keyboards

Sasha Masakowski by Chotika Watanajung

The New Orleans vocalist has added to her musical and conceptual vocabulary, stretching the boundaries of jazz and electronic music in the process.

“He’s so musical. I feel like I learn something every time we play.”

One jazz musician saying that about another isn’t news. For the history of jazz if not music in general, knowledge has been passed on the bandstand and in the rehearsal room. But in this case, the speaker is Sasha Masakowski and she’s talking about Nicholas Payton after their trio—rounded out by Cliff Hines—played an unlikely gig in the Jazz Tent at Jazz Fest 2022.

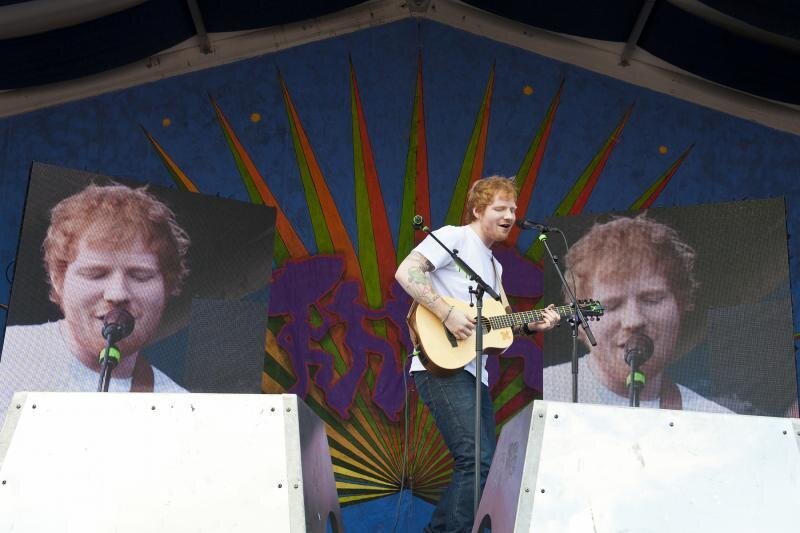

Payton sat at an electric piano with his trumpet, an upright bass, and a laptop on his piano. Masakowski presided over a cafeteria table scattered with a laptop and bits of electronic gear. The table could have been neater, but having the cables visible and accessible makes troubleshooting easier. Hines had a modular synth, his electric guitar, another laptop, and more boxes and devices. Masakowski and Hines responded to the sounds Payton initiated, looping, processing, and adding to them to for Payton to respond to. They created something that borrowed from jazz, dub, hip-hop, and EDM that was true to Payton’s #BAM or #BlackAmericanMusic aesthetic, it deliberately avoided landing cleanly in any musical box, which tested fans or Norah Jones—who’d play next—and those used to usual, more conventional Jazz Tent fare.

For those who never moved beyond Payton’s Young Lion days, the show was likely confounding, and Masakowski only added to the cognitive dissonance because many in the tent first knew her as a jazz vocalist who specialized in bossa nova when she finished at NOCCA. That’s not a part of her musical life that she disowns, but she has moved in more adventurous directions since then. She has a couple of bands—Art Market and Tra$h Magnolia—that scratch different musical itches, and she collaborates with conventional and unconventional musical voices when possible. She participated in the Instigation Festival in January, which pulled together musical improvisors from Chicago and New Orleans for a week of shows, and her Progression music series features Masakowski and like-minded musicians at Chickie Wah Wah on Tuesday nights. This Friday night, she’ll help open the spring season at New Orleans’ Music Box Village.

In retrospect, Masakowski’s musical evolution was probably inevitable.

Her bossa nova period made sense. It was music Masakowski grew up with, and “my voice sits in this really cool range that feels really good when I’m singing Brazilian music,” she says over a late breakfast. She looks back at those recordings as “diary entries” and remembers that period fondly, but when she talks about how young singers need to take control of their careers and their music, it sounds informed by experiences she’s too cagey to volunteer. When producers tell young singers they know how to best present the music, stick to your guns, she advises. “I was constantly disappointed by what other people would do.”

In 2015, Masakowski made her first public foray in a more electronic direction when she and Hines formed Hildegard, an eclectic electronic rock project that was credible on its own terms but didn’t quite land at the time. It flexed very different musical muscles from the ones they were known for, so much so that it was hard reconcile the project with its makers. As such, it can now be seen as a transitional project. Masakowski didn’t want to be stuck in any genre or niche, but because her talent, looks, and professionalism made her marketable, she had people in the industry telling her that no one was sure what to do with her. Her restlessness made her frustrating for people who believed that money could be made with her, but she embraced her changes.

“You’re a perpetual student,” Masakowski says, and she has enjoyed her evolution and growth as she moved from music she could do well to music only she could make. That doesn’t mean she rejected bossa nova, though. “I think a lot of the beats I make now are influenced by Brazilian music—samba, bossa nova, and now baille funk,” she says. She always thought of herself as a composer even though that wasn’t the music she was known for, and she felt like she had a good ear for hooks and melody. “My background in jazz informs the harmony behind what I’m doing and makes it more interesting,” she says.

Masakowski spent a lot of her time between 2015 and the pandemic in New York, where music performance and production merged for her. At the time she was working with musicians Jason Lindner, who played keyboards on David Bowie’s Blackstar, and drummer Zach Danziger. Both had projects that created live, improvised dance music that merged contemporary technology and dance music aesthetics with jazz, hip-hop, and other musical sounds around her. She contributed by using her voice as an instrument, looping it and other sounds that interested her.

“I manipulated them and chopped them up into beats,” she says.

Purists may not hear the product as jazz, but the concept has been in the air with such artists as Flying Lotus, Robert Glasper and Terrace Martin making music that honors many of the values associated with jazz while living squarely in the 21st century. In New Orleans, Terrance Blanchard and Nicholas Payton work in that space as well, Blanchard largely using computers and synths to attenuate the sound of his E-Collective, while Payton’s more aggressive embrace has helped him further flesh out the #BAM concept.

“I used it as a tool to compose for Tra$h Magnolia,” Masakowski says. Tra$h Magnolia gives us the current version of Masakowski the singer, and her voice has the same airy intimacy that made bossa novas the soundtrack for a generation’s daydreams. That it’s not an obvious connection, though. 2021’s Exist EP sounds more like the natural follow-up to Massive Attack, with “art pop,” “experimental pop,” and “experimental electronic” tags on its Bandcamp page to help it find its audience.

It’s easy to hear the technology first because it’s so prominent, but Masakowski found the tools useful to solve the problems composers face. “I have a tendency to think linearly,” she says, but the software helps her find ways to disrupt those patterns. She could change the sounds themselves and the way they’re organized, but that awareness has come with time and practice. “It’s like learning an instrument,” she says.

Masakowski was excited when Payton asked her to collaborate in 2020. “He was a huge inspiration,” she says. “I used to listen to Sonic Trance over and over again.” They came together to play a gig at The Sidebar in early March, and she played it wearing a camouflage-patterned mask that she got the week before while in Japan. With COVID concerns in the air, it made precautionary sense, but it also worked for the presentation of the music. She could hear the whispers as people wondered if it was a health measure or a fashion statement.

A week or so later, everything shut down and with no gigs or tours on the books anymore, they got together with Hines at Payton’s house to record Quarantined with Nick, which is a good early document of what the three do together. The album is very much of its moment with found audio snippets talking about “a life lived in fear” putting obviously human voices in the midst of the percolating sounds. It’s often witty, most obviously on “Charmin Shortage Blues,” which extensively samples a woman saying, “Somewhere along the line they announced Coronavirus. They said it’s gonna affect your immune system, and everybody must have thought it’s going to affect my booty hole.”

Ironically, Masakowski realized while recording the album that she had contracted COVID. She had a mild case, but it was scary when she realized while working on music that she had lost her ability to taste.

They played together regularly as Payton live-streamed shows during the shutdown, and last fall Payton, Masakowski and Hines played the Monterrey Jazz Festival, where she saw some of the puzzled looks that they got at Jazz Fest. She also saw signs of engagement, particularly from teenagers and college-age fans. “They get it,” she says. “I think it’s because young people are interested in the evolution of jazz music.”

Creator of My Spilt Milk and its spin-off Christmas music website and podcast, TwelveSongsOfChristmas.com.