Outlander's Diana Gabaldon Takes MSM to School

In an email interview, the author of the "Outlander" series who came to New Orleans for the Wizard World Comic Con conducts a writing masterclass.

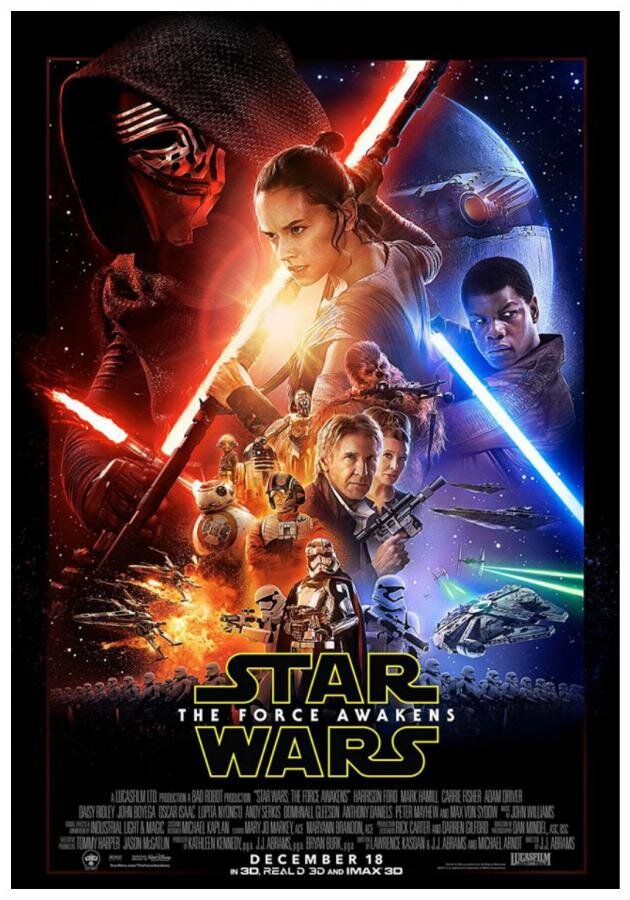

Novelists are usually in short supply at Wizard World Comic Con. Superheroes and pop culture stars are its top-line draws, but this year writer Diana Gabaldon--author of the "Outlander" series--attended the New Orleans convention, along with members of the cast of Outlander, the series on Starz adapted from her books. Her work makes sense at a comic con as her writing blends science fiction, historical fiction, romance, fantasy, and mystery, but she doesn't plan to make too many similar appearances this year as she's trying to finish a book. (Those who want to see her in person can find her public appearances here.)

We exchanged email on the occasion of her visit. Here is that conversation:

New Orleans Wizard World 2019 is upon us!I’m sure you can imagine that a city like New Orleans is bound to have an immense, fiercely weird and beautiful turnout every year. Have you been to New Orleans before?

Yes, I’ve been to New Orleans several times, sometimes professionally, but more often private—my husband and I love the city: food <g>, vibe, history, music—and tubas, particularly. (Every time we go, he comes back with an urge to buy a tuba.)

How often do you tour with groups or appear at events like Comic Con? What does your current schedule look like – hectic, relaxed?

I really don’t ever tour with groups; the closest I come to that is appearing at San Diego Comic Con or NYCC with the Outlander cast/production. We do a lot of different interviews, panels, events, etc., in varying constellations of people, over a period of two or three days, but it’s all within the context of promoting the new (upcoming) season of the show, so limited to that one occasion.

Beyond that, I only do book tours when a new book is released, which means I luckily don’t have to do them often. (Book tours are remarkably grueling and I don’t like being away from home for long stretches.) On the other hand, I get constant (like 30 or 40 a month) invitations to come here, go there, do this, speak at that, etc. Book festivals, writers conferences, library events, awards, you name it. If I accepted half of these invitations, I’d never finish another book and I’d be divorced, because I’d never be home.

So, I pick and choose. Some things—like the Surrey International Writers Conference—I’ve done for 25 years, and will continue doing; it’s immensely stimulating to teach and talk to writers and the atmosphere and people are amazing. Other things are one of a kind, or just happen to occur in a place that I’d like to be for other reasons—which is the case with this weekend, to be honest.

I’ve always loved and recommended a video by Signature Views that gives a brief vignette of you walking us through your writing process. “Want to watch me write?” is an awesome exposé of the rather stream of consciousness way in which you craft sentences. It seems that you put a lot of focus on fluidity of language, symbolic detail, and authentic dialogue, each morsel carrying some sort of weight to chew on. Do you write with the intention to be read closely?

You know, I really don’t think about people reading it, while I’m writing. I don’t actually care about “the readers” in more than a vague sense that I wish them well, but I certainly don’t think about what they want or might think of something I’ve written. (I mean, if you’re lucky enough to have more than one fan/reader, it’s impossible to please everyone, so why try?)

On the other hand, the book had dang well better please me, or why write it?

Everything you use, right down to the twigs and leaves, is a significant, symbolic detail in its own way. What influenced you to write this way? Are there any writers specifically that jump out at you as being role models for you or hold an artistic standard to be emulated, or at least imbued, in your writing?

Hm. Well, there are five specific writers whose skills in one dimension or another were illuminating for me when I began to write fiction: Robert Louis Stevenson (from whom I learned the importance of character and the influence of character on story and vice-versa), Dorothy Leigh Sayers (from whom I learned how to define and examine a character via the subtleties of dialogue—accent, locution, word choice, idiom, etc.), John D. MacDonald, (from whom I learned how to do a series character—one that recurs in every book—and how to capsulize a character and make them unique in a sentence or two), Charles Dickens (from whom I learned the art of ensemble acting, as it were, how to use unique minor characters, and how to do effective emotion), and P.G. Wodehouse (from whom I learned how to use language to comic effect while transmitting information).

Beyond that, I’ve been affected—positively or negatively <g>, by pretty much everything I’ve ever read.

You’ve been known to joke about how long it takes you to write a “big” novel. Your fluid, meticulous writing process seems bound to demand lots of time spent with your characters. You’ve managed to keep readers interested for decades now by cultivating a varied cast of, complete with, in your terms, the mushrooms, the hard nuts, and the onions, breaking up plots and subplots driven by history and action with extended moments of tenderness, romance, and introspection. How long does it take for it all to come together? How much of a challenge is it to maintain this delicate balance, one that every long-spanning sci-fi/fantasy/romance/indescribable series surely warrants yet so rarely achieves?

Well, you have memorable characters in interesting situations of intrinsic and extrinsic conflict, and you write well, is about the sum of it.

To offer one bit of craft advice, though—the way you keep readers turning the pages of a Big Book is to create a constant cascade of questions to which the reader wants an answer. These don’t have to be big questions—any little question will do (though you need a few big ones to underpin the plot): there’s a knock at the door. Do we want to know who’s on the other side? We do. Jamie looks out the window and suddenly Or in in this brief exchange:

“Come lie wi’ me and watch the stars for a bit, Sassenach. If ye’re still awake in five minutes, I’ll take your clothes off and have ye naked in the moonlight.”

“And if I’m asleep in five minutes?” I kicked off my shoes and took his hand.

Do you want to know what he says in return? Yeah, you do…

“Then I won’t bother takin’ your clothes off.”

By the same token, you want to be sure that a sense of action runs through the story, whether there’s any major-league stuff like battles, journeys or confrontations going on or not. You do that pretty simply: just make sure there’s at least _one_ sentence of action (any action; lifting a teacup is fine) in each paragraph.

Example:

“I’m going hunting with Da,” she whispered, bending close. “Mama will watch the kids, if you have things to do today.”

“Aye. Where did ye get—“ he ran a hand down the side of her hip; she was wearing a thick hunting shirt and loose breeches, much patched; he could feel the roughness of the stitching under his palm.

“They’re Da’s,” she said, and kissed him, the tinge of firelight glisking in her hair. “Go back to sleep. It won’t be dawn for another hour.”

He watched her step lightly through the bodies on the floor, boots in her hand, and a cold draft snaked through the room as the door opened and closed soundlessly behind her. Bobby Higgins said something in a sleep-slurred voice, and one of the little boys sat up, said “What?”in a clear, startled voice and then flopped back into his quilt, dormant once more.

The fresh air vanished into the comfortable fug and the cabin slept again. Roger didn’t. He lay on his back, feeling peace, relief, excitement and trepidation in roughly equal proportions.

You can see the sensory stuff working in that brief example, too: sight, sound, touch and smell. Using any three of the senses in a scene gives it a three-dimensional, immersive quality (most beginning writers seldom use anything but sight and sound). [Credit Gustave Flaubert for articulating that bit of wisdom as the Rule of Three.]

I am very slow, both because of the word-by-word pickiness and because of the scope of one of the books (to say nothing of the series as a whole; each book occupies a specific structural position in the series and they’re all linked (and sub-linked) together in a fairly complex (but intuitively understandable) pattern. Also because I have a fairly full life outside the page, too. And then there are the fans and the Price of Fame. <cough>

Bottom line is that it takes me about four years to do one of the Big Books. It used to take about three, but a) the books get more complex as we go along, and also require more internal engineering, to make sure that people who pick up Book Eight without having read the preceding seven will still be able to figure out enough background to enjoy it, without boring the pants off the readers who’ve read all the books multiple times, b) they require a lot of research, and c) I have a lot of intelligent, interesting, super-engaged fans, and while I love to talk to them, it does take time. Social media is great, in that you can manage how much time you spend with it, and there are ways of dealing with the immense amount of email and as noted, I’m careful about how many places I go in a year—but it all adds up.

You’ve been known throughout your career to hold a certain disdain for “stupid women” and weak portrayal of female characters in media and art. Claire has become a sort of cult-like feminist figure, and one whose unique story arc indeed asserts a progressive angle on historical drama. How much time do you spend with Claire? Do you find she chooses where to go next, or do you have a plan for her? Give us a peek into Claire the onion, your process of personality revelation, and your thoughts on the impact her character has had (whether you intended her to or not) within the politically charged media at large.

You—like a lot of people since the show started—appear to be working under the assumption that a) it’s All About Claire and b) she’s my favorite character and c) the main focus of the series. I’m afraid none of those assumptions are true, though of course everyone is entitled to his or her own interpretations.

(In fact, she’s not “the” character that everyone is most interested in. Most people are interested in the story of Jamie and Claire together, though they’re deeply interested in them singly. When considered singly, though, Jamie’s story is by far the more interesting: he’s living through times of desperate historical conflict and is usually in deep emotional stuff, as well, owing to his inborn sense of responsibility. Claire’s solo story (during their 20 years apart) is a pretty standard woman-of-the-'60s, career vs. family responsibilities, distance in marriage story; you’ve read stories like it a hundred times. (Mind, this doesn’t mean those stories are cookie-cutter or inconsequential; the fact that Claire is Claire, though, means that her story and how she responds to her circumstances will be unique (and, we hope, engaging), even if the parameters are familiar. And then, of course, there’s the time-travel, husband in another century, baby not your present husband’s child complication in her particular love triangle….)

For what it’s worth, I don’t actually go around inveighing against women who appear weak in media or art; they can have a purpose—I think you must be extrapolating from my answer to the chronic exclamation/compliment: “Oh, you write such strong women!” To which I’ve always just answered with the truth: “Well, I don’t like stupid women; why would I write about one?”

As it is, people often assume Claire is “the” narrator and thus the most important character, just because her stuff is written in the first person. (“I” did this or that, rather than the third person, “She” did this or that.) In fact, I chose to use the first person there just because it was the easiest thing to do and I saw no point in making difficulties for myself with my practice book. (In later books, there are a number of different points of view, though Claire’s is the only one that stays in the first person—just because that’s how she came to me, so that’s how I hear her.)

As for symbols of feminine agency…is it old-fashioned to say “gag me with a spoon”? I don’t dismiss feminist politics, and if my books have relevance to people urgently concerned with such things, I’m glad to hear it. But (from my individual point of view), books written primarily with any sense in mind of political agenda, whether gender politics, identity politics, intersectionality, etc. tend not to be books I like or find interesting. I sure as heck don’t think about such things while I’m writing.

Just of curiosity, though--how many people do you know who do like stupid women?

On the film adaptations of your work: Hank Steuver of the Washington Post recently wrote about what he thinks is the magic between Jamie and Claire: “Jamie and Claire deal with all sorts of external melodramatic dangers, but together they might as well be gorgeous unicorns. They don’t bicker. They don’t interrupt one another. He doesn’t ramble on about battlefield heroics; she doesn’t start in with monologues about electricity and indoor plumbing. Their presence within a shared present asks the viewer: When was the last time anyone really heard what you were saying?” In other words, they communicate, a seemingly minor yet tantalizing facet of their relationship. How important was this facet of their relationship in the TV adaptation of Jamie and Claire? Does the TV version of Jamie-and-Claire live up to the Jamie-and-Claire of your mind? Did you have any say in the show’s casting?

Well, TV and its source material are always going to be different. They have to be, owing to the limitations and variations of the separate media (I’ve written graphic novels, comic books and one TV script; I understand what you can and can’t do on film as compared to novels, and vice-versa. I also understand how you tell a story in a visual medium, as opposed to text.)

That said, I think the Outlander production does a really good job of adaptation and how far that adaptation succeeds depends mostly on how well they grasp and execute the main characters. The actors throughout the production have been absolutely fabulous, and Sam [Heughan] and Caitriona [Balfe] have known Jamie and Claire intimately from the beginning.

No, the actors don’t look anything like Jamie and Claire look in my head—how could they? But there’s no reason why they should; if I were to draw a picture of exactly what Claire and Jamie really look like, the entire world would look at them and go, “That’s not what they look like!” Because everyone—well, almost everyone; there are actually people who aren’t able to visualize people from a printed description, which is kind of fascinating—evolves their own interior version of the characters when they read.

What’s important is the degree to which the actors can embody the characters—and Sam, Caitriona, Rik, Sophie, Lotte et al are very good at that.

My mom recalls needing to go to "bodice–ripper "section of the book store to buy Outlander shortly after it was released in 1991. She blushed knowing her mother and the neighbor next door had read (and presumably enjoyed) the same steamy scenes. It is clear your books have huge cross-genre appeal, even more so now that it has come to the screen. Who did you imagine your audience to be when you first wrote Outlander? Even further food for thought: “I Give You My Body” is a fascinating expose of how you flex certain elements of the art of sexual writing. Can you speak to any of the techniques you discuss in this piece, and how you incorporate them in your writing?

You know, there are a good many female writers of romance novels who would find “bodice-ripper” insulting and demeaning. (If we’re talking feminism here, I mean, probably not a good idea to throw shade at women who write fiction primarily for other women.) I don’t write romance novels myself, but I do enjoy them—and I’m not a fan of that term.

I didn’t imagine any audience when I wrote Outlander; I wrote it for practice, in order to learn how a novel worked and what sort of effort went into writing one. Then Stuff Happened, and here we all are…

But the important thing is that since I never expected anyone to read it, I felt entirely free to do anything I wanted or thought necessary, which probably resulted in a much higher degree of complexity and emotional honesty than the book might have had if I’d know how many people might be reading it.

Consequently, I’ve seen my books sold (with evident success) as: Fiction, Literary Fiction, Historical Fiction, Historical NON-Fiction (really), Science Fiction, Fantasy (not the same thing as SF), Mystery, Romance, Military History (true; several of my books have been selections of the Military History Book Club over the years. I do good battles), Gay and Lesbian Fiction, and…Horror. (Also true. I once beat both George R.R. Martin and Stephen King for a Quill Award in the “science-ficition/fantasy/horror” category).

Every reader brings themselves to the experience. Background, prejudices, education, expectation—everything a person is will influence what they perceive in a book and what effect those perceptions have. (This also means that people can re-read a complex book—like mine—repeatedly, and find different things in it each time, as they move into different periods of their lives and have a greater history of personal experience.)

I Give You My Body… is a small book of tradecraft. (It’s only 30,000 words, which is why it’s an ebook, though I’ll probably publish a tactile edition of it one of these days.)

There are a lot of really terrible sex scenes around (did you see that piece in The Guardian a few weeks ago, with the award for Worst Sex Scene(s) of the Year? I’ll note for the record that the six nominees who were quoted were all men, and that it was glaringly obvious how they came to be nominated: they all violated the first Law of Good Sex Scenes: it’s about the exchange of emotions, not bodily fluids.

And the Second Law is like unto the First: A good sex scene is personal; it can only have taken place between these two unique people. If you can take your sex scene and substitute the names Ana and Christian (or Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny) and have it play the same…you’re not doing it well.

The Third Law is actually a corollary to the Second: Good lovers talk in bed. That’s how you make the scene personal by revealing their personalities; dialogue is the single best tool a writer has for revealing and developing character.

Example:

“It was like making love to a block of ice.” It had been. It had also wrung my heart with tenderness, and filled me with a hope I’d thought I’d never know again. “Besides, you thawed out after a bit.”

Only a bit, at first. I’d just cradled him against me, trying as hard as possible to generate body heat. I’d pulled off my shift, urgent to get as much skin contact as possible. I remembered the hard, sharp curve of his hipbone, the knobs of his spine and the ridged fresh scars over them.

“You weren’t much more than skin and bones.”

I turned, drew him down beside me now and pulled him close, wanting the reassurance of his present warmth against the chill of memory. He was warm. And alive. Very much alive.

“Ye put your leg over me to keep me from falling out the bed, I remember that.” He rubbed my leg slowly, and I could hear the smile in his voice, though his face was dark with the fire behind him, sparking in his hair.

“It was a small bed.” It had been—a narrow monastic cot, scarcely large enough for one normal-sized person. And even starved as he was, he’d occupied a lot of space.

“I wanted to roll ye onto your back, Sassenach, but I was afraid I’d pitch us both out onto the floor, and…well, I wasna sure I could hold myself up.”

He’d been shaking with cold and weakness. But now, I realized, probably with fear as well. I took the hand resting on my hip and raised it to my mouth, kissing his knuckles. His fingers were cold from the evening air and tightened on the warmth of mine.

“You managed,” I said softly, and rolled onto my back, bringing him with me.

“Only just,” he murmured, finding his way through the layers of quilt, plaid, shirt and shift. He let out a long breath, and so did I. “Oh, Jesus, Sassenach.”

Anyway, I Give You My Body discusses what does and doesn’t work in writing sex scenes, and provides a lot of examples (mostly from my own work, as that was much simpler in terms of copyright permissions), with embedded commentary and analysis.

It’s coming on about four and a half years since your last addition to the "Outlander" series was published. We are told the ninth installment, Go Tell The Bees That I Am Gone, is in the works. As you research “Bees,” do you find yourself busier than usual, or with more free time? Are there plans to adapt or further develop the Lord John Grey series in any capacity within the TV adaptation of Outlander?

Life is pretty much nuts (though usually in a good way) all of the time. But I try to write every day, regardless of whether I have a little time or a lot.

I’m sure there will be more novellas—they’re a lot of fun, and let me explore side-stories and minor characters—but I don’t plan them out ahead of time; ideas just come along and when something starts bubbling up, I start writing it. (I normally do work on multiple writing projects at once, whether that’s two or three different scenes from the same book, a scene and an interview (like this one) or other PR stuff, an essay on some nonfiction(ish) topic, a book review, etc. It keeps me from ever having writer’s block.

As to a Lord John spin-off TV series, I’m all for it, but it’s not my call. Keep your fingers crossed!

Finally (the fun question – I saved it for last!): Is there anything of note – characters, plot points, details, anything – that had to be dropped from the books that you secretly wish could’ve made it into the TV series?

<laughing> Yes, hundreds. They just don’t have the room to do anything like the stuff I can do in a novel, so a ton of small interesting moments go by the board, and no few big ones, too. The major overall lack, though, is the story’s sense of humor. You see it often in Season One, intermittently in Season Two, but really not since then. A good bit of that is simple film logistics, though: much of Claire’s humor is interior monologue—she’s funny because of what she’s thinking about things—and you can’t do that on film without constant voiceovers, which are a terrible intrusion/burden in telling a visual story.