Neal Adams Fights the Bulk

The comic book legend has brought common sense to character design for 50 years.

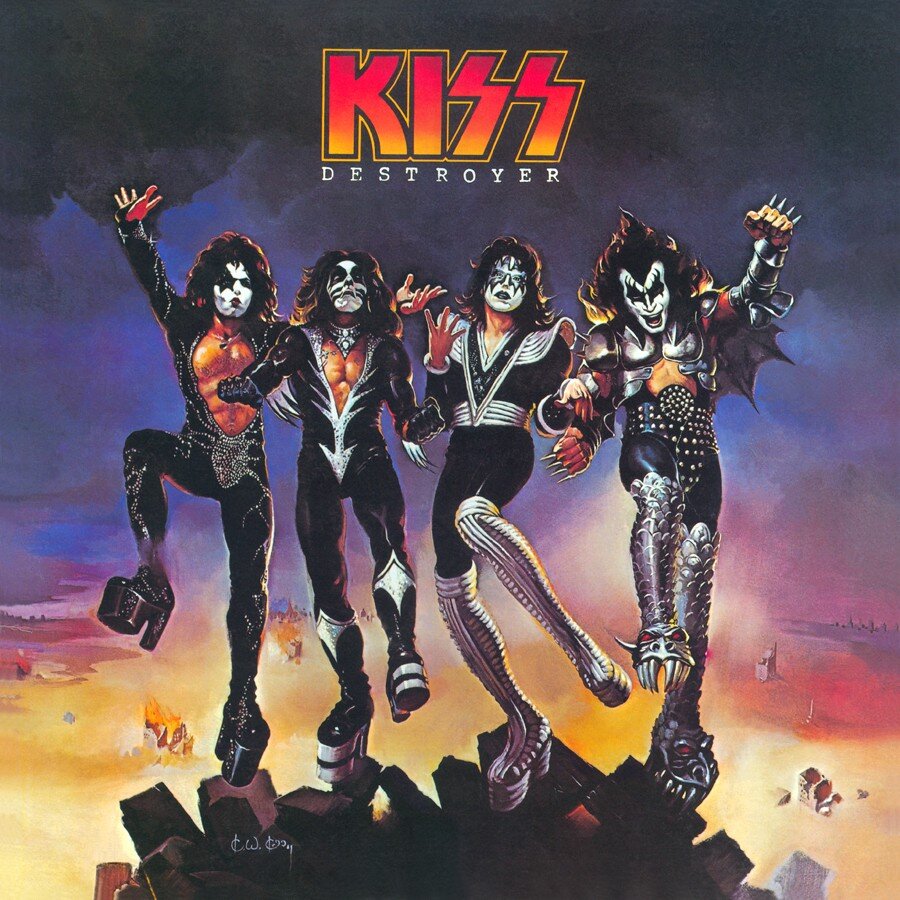

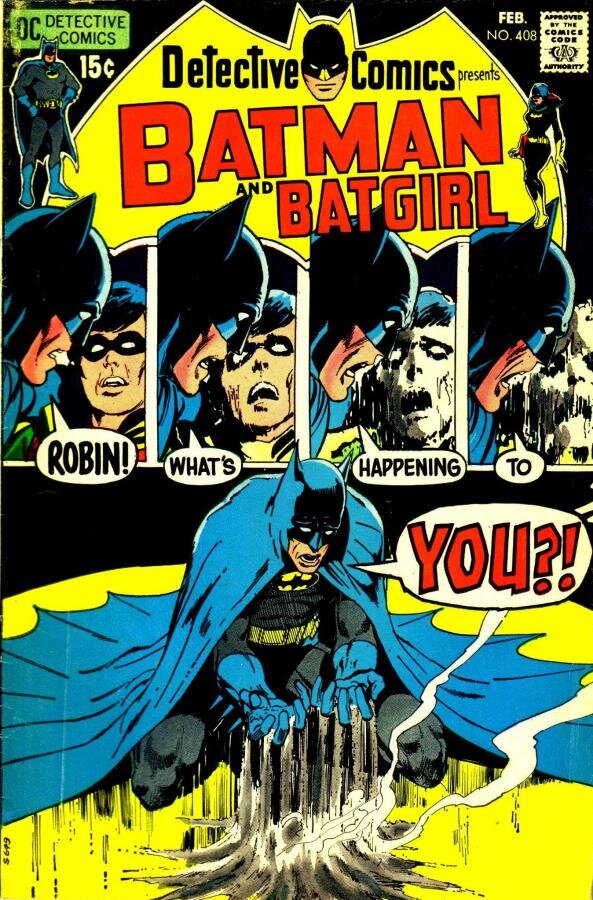

In the 1970s, Jack Kirby and Neal Adams were the two gravitational poles of comic book art. Kirby’s work was all space-aged, visual dynamics, with cosmic impact in every brush stroke, while Adams’ work was far less obviously stylized. His figures were less blocky and musclebound than those of his peers and certainly less so than those drawn by Kirby, whose superheroes were often costumed tanks. Most of their peers and those who came into the comic book business later show the influence of one if not both.

“Everybody worked off the same mold,” Adams says. “Flash looked like Batman. Batman looked like Superman, but people aren’t like that. Runners look different from wrestlers, and bodybuilders look different from everybody. Batman needed to be lithe and athletic, Superman could be bulkier.”

Adams first approached DC Comics in 1959, and like many artists of his generation, he had a commercial art school education that prepared him first for a career in advertising, where he did storyboards and ad campaign mock-ups. In 1962, he did the newspaper strip “Ben Casey,” bringing a then-unprecedented level of visual realism to newspaper comics. Subsequent generations of artists learned to draw comics from other comics; Adams learned figure drawing and human anatomy, so his characters had a clear, recognizable humanity. His superhero art was also considered “realistic” by fans - certainly compared to his peers - and he was one of the few artists whose work affected the value of a comic on the collectors’ market. He continues to work today, having done the Batman Odyssey mini-series in 2011, and the five-issue The First X-Men in 2012.

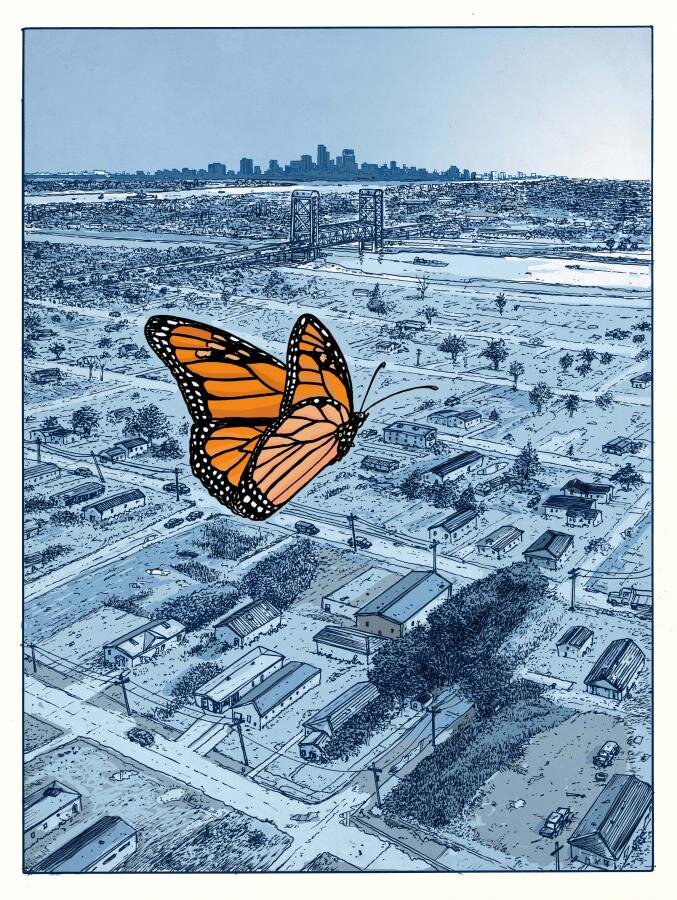

Adams will be in New Orleans for the Wizard Comic Con, which runs from Friday through Sunday at the Morial Convention Center. Comics legends Stan Lee, Chris Claremont, Marv Wolfman and Mike Mignola will be there, along with a battalion of contemporary comic artists and pop culture figures including much of the cast of The Walking Dead, Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn from The Terminator, Matt Smith from Doctor Who, actress Pam Grier, WWE Diva champion A.J. Lee, J. August Richards from the Joss Whedon posse, Elvira, Robert “Freddy Krueger” Englund, and many more.

“It’s like the circus has come to town,” Adams says, and it’s a far cry from the early conventions he attended. He attended the first San Diego Comic Con - today, the biggest convention - when it was a gathering of 140 or so people. “Anybody who had money in their pocket could fit around four tables for lunch,” he says. Early cons were focused on collectors; guest artists and writers were secondary to the opportunity to fill in gaps in collections as other collectors sold back issues.

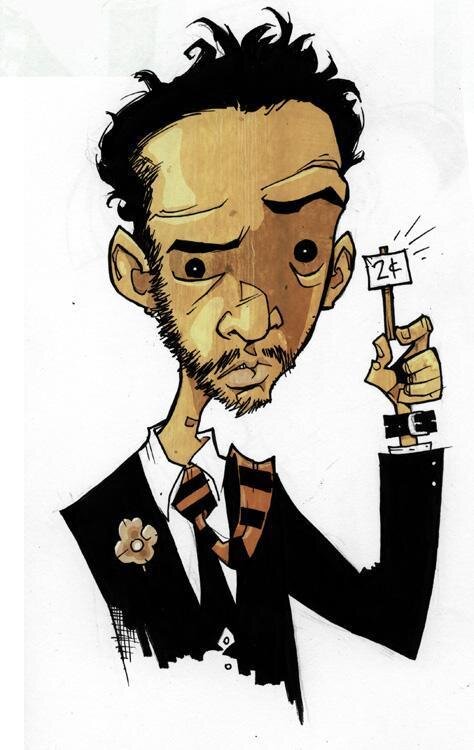

“When this began, it was these fans who actually were doing illegal business by buying comic books out the back of their local wholesaler and selling them in their garages or at a hotel, buying them for 15 cents and selling them for two dollars,” Adams says. “Those guys ended up becoming the direct sales market or comic book stores. It was teenagers beginning to take over the business.”

Comic conventions, on the other hand, are no longer a series of small, local organizers putting together events in airport hotel banquet halls to companies. Wizard ended its sci-fi-leaning pop culture magazine in 2011 and got into the comic con business, reflecting its interests on trade show and convention hall floors. This year will do 16 cons around the country, and other companies are getting into the business. They’ve become pop culture celebrations and gatherings of the nerd tribes, and their fascinations including cosplay and sci-fi makeup have now found television homes in shows on the SyFy Network. Autographs generally cost money, and attendees can pay to be part of meet-and-greets with some of the industry’s biggest stars. This year, Stan Lee and original Mighty Morphin Power Ranger Jason David Frank will host such events.

“It’s going to cost you some money, but you’re going to be able to get the stuff you couldn’t get all year around,” Adams says.

When he talks about comics’ place in the pop culture universe - “We’re the rock ’n’ roll of the industry” - he does so with a mix of insight and showmanship that has always threaded itself through comics’ history. “We do graphic novels and they turn them into TV shows and movies, computer games. We’ve become the feeder for our entertainment, and we always have been.”

Adams used his stature in the industry to make it easier for artists to move to between Marvel and DC. Many worked for one company or the other, and if they worked for both, they did so under two different names. He remembers a conversation he had with Stan Lee about drawing a comic for Marvel while he was doing one for DC

“So what should we call you?”

“How about Neal Adams?”

“Well, some publishers are kind of sensitive about that.”

“I’m not.”

“When we hire somebody, we don’t want them working for the other company.”

“Well, goodbye Stan.”

“No, no, it’s okay.”

That exchange may be suspicious in its pithy precision, but Adams is a storyteller. He’s likely told the story a few times, and he has a history of using his art to make comics about something meaningful. During his famous run in 1970 on Green Lantern/Green Arrow, he brought superheroes face to face with very human problems instead of supervillains. During the series, Green Arrow’s teen sidekick Speedy became a heroin addict. For similar reasons, he claims one of his favorite comic books is Superman vs. Muhammad Ali, a one-off published in 1978. Editor Julius Schwartz came up with the idea to exploit the popularity of Ali, but Adams took on the book to help address the white, northern, urban racists who gave themselves a pass because they weren’t southern. “In New York, we were the last to realize we were bigoted,” he says.

During a recent episode of the Fat Man on Batman podcast, Adams told filmmaker and comics writer Kevin Smith about his role in breaking the color barrier for superheroes. He found the premise that Green Lantern’s ring would seek out the good, true, and brave on Earth and keep finding white, country club types hard to accept and argued for the introduction of John Stewart, the first black Green Lantern. He also worked to have him colored in tones closer to ones found on real African Americans than comics had previously used.

Adams also used his stature in the ‘70s and ’80s to fight for creators’ rights. He tried to start a comics creators’ union, and he worked to get better, fairer treatment for artists, which among other things meant publishers returning pages of original art to the artists who drew them. The companies didn’t pay for the pages, only their use, and the growth of the comic art market made these pages a potential source of income at a time when the page rate for artists was generally a pittance. At the time, original art was often given away as goodwill token by company executives when negotiating deals, or were left to mold or rot in company basements.

“If you’re sufficiently good at what you do, you really do have a responsibility to undo some of the bad shit,” Adams says.

Still, Adams embraces what comics first and foremost are. “Comic books are like jazz,” he says. “It’s ground-level stuff.” His working class roots seem to take pride in that. They may have roots that he traces back to Egyptian hieroglyphics, and they may have spawned the dominant mode in action movies today, but “in a weird way, it’s not important. It’s comics.” He brings the same energy and sense of pride that he shows in discussions of justice to an explanation of his costume design for Havok, one of The X-Men, applying the same clear logic to something far more ephemeral.

“The design was functional to his powers,” Adams says. “There were no highlights on his black costume because no energy was escaping him, no light bouncing off. It was absorbing energy. That thing on his head was meant for projecting energy.”

Neal Adams will also sign books Thursday from 4 to 7 p.m. at More Fun Comics.