Kero Kero Bonito Searches for Sense in a Messy World

The once-kitschy poptimists turn to noisy existentialism on their new album, "Time 'n' Place."

Kero Kero Bonito has undergone a sea change. Their sound, once radically cheerful, matured into angsty uncertainty with the release of Time ‘n’ Place in early October. The British pop project started as a simple synth trio, with Gus Lobban and Jamie Bulled manning the boards, and Sarah Midori Perry singing and rapping, alternating enthusiastically between English and her native Japanese. Now, suddenly, they’ve morphed into a live band, replacing their kitschy, J-pop inspired anthems with seething noise miniatures, complete with bass, drums, guitar and analog industrial effects. They’ll bring their retooled live show to a sold out Hi-Ho Lounge Wednesday at 9 p.m. with support from Tanukichan.

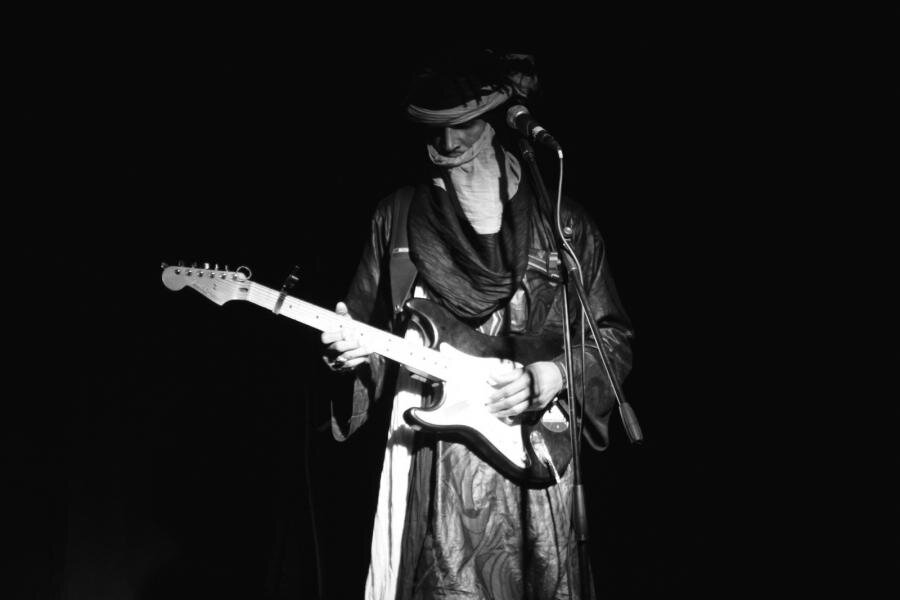

A few shows into their tour, KKB are excited about their new setup, which includes drummer Jennifer Walton and guitarist James Rowland, who contributed extensively to the new album. “We’ve always made dance music and club-influenced music, but adding the guitar and the drums adds so much energy,” says Lobban. “It’s like simply watching someone hit a drum kit and hearing that in the air just does something to people. They get so much more energized.”

On the album, though, the change of pace is more disconcerting than energizing, at least upon first listen. KKB fans have become accustomed to tidy pop tracks that wrap Perry’s shimmering voice neatly in bubblegum synths, so hearing it shrouded in reverb and static is initially jarring. “All of us went through a few things in our lives, and we wanted to use real instruments to let those emotions out,” Perry says. “It’s different when you’re hitting something.”

Album opener “Outside” immediately sets the tone with a blast of warped guitar power chords. “It goes all the way there straight away,” Bulled says. “You’re outside, out in the open. It takes you to a place, which is a theme throughout the record. It’s quite a defining start.”

KKB’s themes have darkened along with their aesthetic. The lyrics on their 2016 debut LP, Bonito Generation, read like pep talks for troubled Millennials, but those on Time ‘n’ Place feel deeply personal and subjective, tied inexorably to the scenes they paint. “For me, it started earlier this year,” Perry explains. “My brother messaged me, out of nowhere, a picture of my childhood home demolished. There was a flatland where I used to sleep, where I spent my childhood. It was completely gone. And last week, I got a message from my mum that my primary school is now completely closed. Also, my childhood pet passed away. So it feels like my physical past is slowly disappearing. It’s just a memory, nothing to refer back to.”

Places disappear, but the spaces surrounding them remain. Perry is interested in the spaces that humans cannot colonize, particularly the sea and sky. She daydreams of flight on “Flyway” and “Dear Future Self,” and of “swimming across the sea” on “Swimming.” Air and water are essential to her look as well. “The reason I started to wear glitter came from seeing this study that said when humans see something shiny or sparkly, it reminds us of the shiny-sparkliness of the sea,” she says. “When I look down at the sea or up at the sky, it’s like there’s still magic in this world. That brings me hope.”

Perry’s shiny-sparkliness gleams through the walls of noise that cover it on Time ‘n’ Place. It’s the driving force behind KKB’s viral success, making the band an instant meme and a message board darling. As one Twitter user recently put it, “It’s that genre of music you like because you think it’s your girlfriend.” Their fandom exists mostly in the perpetual daydream of the Internet, as ubiquitous as the sea and sky and equally impossible to occupy physically. “Those pockets are where it’s at for us,” says Lobban, referring to forums like Rate Your Music and r/indieheads. “It’s like a dog whistle. We have this instant kinship with people who see the world and communication in that kind of way. It was really key in allowing us to bypass the trad gatekeepers.”

Fittingly, Perry was recruited to the band through MixB, a message board for Japanese expats in London. Lobban and Bulled, friends at university and mutual lovers of J-pop, posted an ad there looking for a singer/rapper. “Without the Internet, we wouldn’t have started KKB,” Perry muses. “I think the beauty of the Internet is that there’s no physical barrier. You can do something with someone who lives on the other side of the world. I’ve done collabs with people I’ve never physically met.” Most of the outside collaborators on Time ‘n’ Place contributed remotely, including a “campfire chorus” on “Sometimes” comprising singers who sent their parts in from London, L.A. and Olympia, Washington.

Time ‘n’ Place plays like a jigsaw puzzle, pieced together oddly at its many stops and starts. “It was recorded in different phases, so the tracks will have stuff that was on the demo that we recorded at home, stuff that we recorded when we herded the band into the studio, stuff that I added later on, and then other weird field recordings from times in our history,” Lobban says. “Everything is collagic now, but it’s so random. You can take a photo on your phone and then print it out and rescan it. It can be a photo of an old building or a new building that’s made to look old. It’s so arbitrary. [Time ‘n’ Place] is about trying to make some kind of balletic sense of that mess.”

The concept is far from straightforward. It’s best illustrated on album closer “Rest Stop,” which begins as a gorgeous ode to a roadside oasis but dissolves halfway through into a yawning abyss of noise. “It was tempting to end it with a poignant statement,” Lobban admits. “When you’re growing up, you try to attach some kind of narrative to your life and all the things going on around you. But really, there is no narrative. You make up your own narrative. Other than that, it’s all just noise. Really, there’s no other way you could end this record besides a mess because that’s all it really is. It’s all anything is, essentially.”