Jim McCormick Makes the Run

For decade, New Orleans' Jim McCormick has been writing songs on Music Row in Nashville. With Brantley Gilbert's "You Don't Know Her Like I Do," he has his first number one. What does that mean for him?

After a decade of writing in Nashville, New Orleans' Jim McCormick has finally penned a number one hit.

Updated:Nashville is referred to derisively as "Nashvegas," but Nash Angeles may be more accurate. I visited songwriter Jim McCormick a few years back, walked the songwriter's circuit with him and a friend and saw the hustle at a pretty naked level. Country music is built on an army of songwriters giving marketable young men and women something to sing, and one night we dropped by a showcase for a new artist that was aimed at songwriters. The half-hour set was intended to give them a sense of what this guy in a black hat and a Ramones T-shirt could do so they could start pitching material for him.

McCormick's friend had written top ten songs for female artists including Wynnona, so beautiful young women wanted to write with him. Maybe they thought they could be a part of a hit song, but more likely they hoped that if the publishing company liked the song, the woman who co-wrote it could sing the demo that would be used to pitch the song to managers and producers. Then, the powers-that-be would hear her voice and even if didn't like the song, they might like the person singing it.

There's no romance in the business at this level, and McCormick makes no bones about it. He's from New Orleans, where he had an underground rock band, The Bingemen, in the '90s before finding his musical voice in country. He started commuting to Nashville to break into the Music Row community 12 years ago and moved there to work at songwriting full-time nine years ago. He's had album cuts with artists including Trisha Yearwood, Randy Travis, Tim McGraw and Jamey Johnson. His first single to get significant chart action was Luke Bryan's "We Rode in Trucks" in 2009, which peaked in the high 20s. Recently, he had two songs enter the Country charts at the same time--"When I Get It" by Craig Campbell and "You Don't Know Her Like I Do" by Brantley Gilbert. The two songs moved up the charts more or less neck and neck until "When I Get It" stalled in the 20s, leaving the Gilbert song as his best bet for a number one. Album cuts help pay the bills, McCormick had said before, but number ones affect your life. On the week of July 14, "You Don't Know Her Like I Do" topped the charts.

"I've never had a song go this high," he says. "So I've never experienced the feverish pitch with which you look at these charts on a daily basis. It's enough to give you a heart attack. When you get up in that rarified air, when the total weekly spins is just over 60,000, the difference between you and the next guy might be 80 spins. As it gets up higher and higher, you almost can't take your eyes off the charts. You've got to compartmentalize or it'll drive you nuts. The real time data can change hour to hour. At noon you might be the number one song, and by three you're the number three song. It's the weekly tally that matters most."

McCormick was aware of the chart positions of his previous singles, including Joanna Smith's "Georgia Mud," but when your songs are in the 20s and 30s, the numbers aren't as mesmerizing. In the top ten? "It's worse than Facebook."

Nashville is an industry town, and he recognizes the role of everyone involved. "All credit is due to the record company's promotion department," McCormick says. "We wrote the song, yes. Dan Huff produced the record and they made a great record on the song, but after that it was out of our hands. And Brantley was working his ass off out there to ingratiate people to him and the song. I owe him a great debt of thanks for all the work he did to take it up the charts." As much as that sounds like the politic thing you'd expect him to say, he's being real. He's seen enough songs hit or miss inexplicably and had enough unpredictable setbacks to make him appreciate how much has to happen for this level of success.

" It's such a minor miracle when this kind of thing happens because so many things have to go right and at each step along the way a million things can go wrong and derail it," McCormick says. A case in point is the Craig Campbell single that stalled. "A great artist, a lot of momentum, and for whatever reason it didn't gain traction and it just made it up to number 28 before it died," he says. "Why things don't work is as mystifying as why they do."

"You Don't Know Her Like I Do" had the advantage of being Gilbert's second single, and "Country Must Be Country Wide" before it went to number one as well. Still, back to back number ones for a new artist are unusual. He's not, McCormick points out, a Chesney or McGraw, or even an Eric Church or Luke Bryan. "Getting to number one wasn't a foregone conclusion."

At the moment, having a number one hasn't changed things much. If his phone is ringing more than it once did, he doesn't know it. He works for the publishing company BMG Chrysalis, and they and his manager Dale Bobo set his schedule for who he'll collaborate with when. They're likely getting more requests from people who want to write with him, he concedes, but he trusts his team. "They've been working me very well for a couple of years now," he says. "I think we're seeing the fruits of our labor."

He also hasn't seen any money yet and doesn't know when he will. "I haven't been here before." But since we last talked about how the money breaks down, the economics of songwriting got worse. "These days an album cut won't pay your bills," McCormick says. "A number one will pay your bills and them some." The writer gets paid based on the number of radio spins a song gets and how many records it sells, but his percentage is a small one. " It's a pennies business. Nine cents per song per album, and the copyright owners split that. It's almost impossible to stay in business without singles, though I did it for a long time." Right now, he feels his success in largely ephemeral terms. "It allows me to feel a little better about myself and check off some boxes that should have been checked off long ago."

There was a time when the artist was largely kept out of the songwriting loop, but in the decade or so that McCormick has been writing, that has changed. He has written with a number of artists in addition to Gilbert. Luke Bryan has been one of his most enduring relationships, having written perhaps three dozen songs together, with Bryan cutting seven or eight of them. He has developed relationships that have allowed him to go on tour with Bryan, Gilbert and Jason Aldean and see country music fans face to face and see what music coming to their towns--often rural--meant. "They're buying a pretty expensive ticket and they're coming to a show that could be the biggest thing since Christmas to happen in their town, and they're there with their fists in the air," he says. "These are the young adult children of parents who worked all their lives and were let go without a gold watch, even. These are the children of the people who are being shit on by the system right now. There's a lot of aggression."

These days, rock is a fairly common part of the country sound. The headliners at Bayou Country Superfest on the Memorial Day weekend in Tiger Stadium have more in common with Voodoo's headliners in terms of production and show than they do with Jazz Fest. McCormick has long made his affection for arena rock one of his selling points as a writer --something you can hear in the Springsteenesque "We Rode in Trucks."

"Ozzy Osbourne's first two albums were huge influences on me."

The growing influence of rock has extended to some of the eternal verities of Nashville songwriting that are proving to be less than eternal. When he got to town, a Nashville song was a concrete song, but that's changing. "As much as I value the awesome craft of the great songs, I value my Jackson Browne ambiguity."

He's also been around longe enough to see the nature of the artist change. Not only can they be more rock than they once were, but they can be more experienced. There was a time when Nashville seemed to want to introduce an artist to the world and preferred less experienced talents to ones that had done their time on the live circuit. Now, "Zac Brown and The Band Perry are two of the biggest artists we have in the format," he says. "They were around for a long time building their audience. Brantley's also been doing it. I don't know if that's a trend inside record companies to look for groups that already have a little traction proven so that the bet is secured because there's very little room for trying things out that look like longshots. The market has shrunk so dramatically in record sales that if they come out with an artist, they really want to know that somebody's there to buy the records. Caution rules the day."

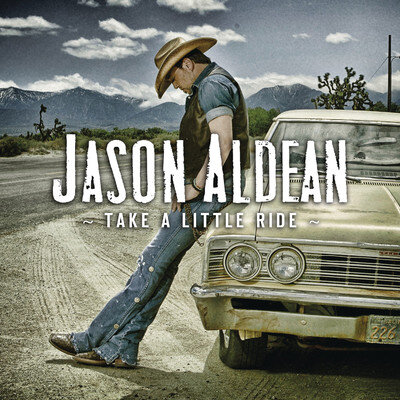

Tomorrow McCormick will have a writing session with someone, and he'll have one the next day and the next day, and so on. What he does isn't governed by self-expression. It isn't about him, and isn't subject to the whims of a muse. He meets with a writer or a young artist and starts. The challenge is keeping it fun, but having a number one certainly helps, and having a good prospect behind it doesn't hurt. "Take a Little Ride," a song he co-wrote with Dylan Altman and Rodney Clawson for Jason Aldean, reached number one at iTunes on its all-genre chart when it was released.

As for "You Don't Know Her Like I Do"?

"I was thrilled when they cut the song; I was thrilled when it made the record. It made the run. They don't all make the run."

Update 9:50 a.m.

Just how business is Nashville? Jason Aldean's upcoming tour will be sponsored by Coors, who asked if he could change a line in "Take a Little Ride." He agreed, so the line that once was "swing by the quick stop, grab a little Shiner Bock" will from here on out be "swing by the quick stop, grab a couple of Rocky Tops." I haven't asked McCormick yet if Coors gets songwriting credit.

You can now get My Spilt Milk in your Inbox. On Friday mornings, "Condensed Milk" - a digest version of the week on the website - will be sent out via email. It's free, and your email address is safe. I won't sell it, give it away, or spam you. To register, look down the right-hand rail on theMySpiltMilk.com home page.