Jazz Fest Preview: Public Enemy Didn't Change; The Culture Did

The hip-hop provocateurs remain confrontational as the culture tries to embrace them.

Seminal hip-hop outfit Public Enemy was not always the media darling it is today. Before its ascendancy to icon status, the group, which plays Jazz Fest on Friday, was in many spheres considered a threat to public decorum, frequently lumped in with radicals like the Black Panthers and the Nation of Islam.

When it burst onto the hip-hop scene in the 1980s with the pioneering It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, the group quickly gained recognition as one of the most transgressive—and dangerous—musical acts in recent memory. Pioneering in that they introduced a rap style that was intense, aggressive, and socially conscious. Dangerous in that PE’s fervent social awareness often manifested itself in political vitriol.

That they became one of the most lauded musical acts in history seems to have more to do with a shifting cultural milieu than with any relenting in PE’s invective (and helped along by public endorsements by music luminaries Bjork, Eminem, and Kurt Cobain). Today, critical accolades for the group are overwhelming and virtually ubiquitous. Rolling Stone ranked Public Enemy number 44 on its list of “The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.” Public Enemy is frequently cited as the cornerstone of hip-hop, and Nation of Millions is often championed as the first great hip-hop album.

Public Enemy’s decades of achievement culminated in their induction into the Rock & Roll Hall and Fame in April of last year. “It was great for the genre,” says Chuck D, Public Enemy’s leader and MC. “And it was great paying tribute to Harry Belafonte and Spike Lee,” who delivered the induction. Public Enemy are now just one of four hip-hop groups to have gained this recognition, along with Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Run-D.M.C. and The Beastie Boys, all of whom Chuck D cites as major influences.

Assimilation into the mainstream musical canon may explain why, in recent years, Public Enemy has attracted the label of “old school,” a moniker that, when applied to rap groups, is not wholly positive. (Outrage erupted, for example, after an intern at NPR wrote that he’d keep Nation of Millions on a “metaphorical shelf.”) It’s a classification that’s surprising given the group’s history of political instigation. Not to mention a discography that continues to be sampled and remixed by everyone from Kanye West to Benny Benassi.

It is true that Chuck D has recently been known to very publicly lament elements of current culture, and rap culture in particular. During our conversation, he spouted some lofty philosophical imperatives that, if not for the group’s 27 years of proselytizing, might smack of a paternal self-righteousness: “Corporations—I call them corp-plantations. They’ve altered the climate of the culture of youth.”

Nonetheless, it’s indisputable that Public Enemy changed the game of hip-hop. Chuck D, Flavor Flav, and the Bomb Squad achieved a level of political provocation and social resonance that most bands never attain. The political legitimacy of Public Enemy is particularly evident in light of the advent of “reputation rappers” (Chief Keef, Lil Wayne, 2 Chainz) that promote what Chuck terms a “passive consumerist mentality for the Black male.”

Songs like “Rebel Without a Pause” reflect a characteristic militancy in the music as well as the words. A trumpet sample from The JB's "The Grunt" blares and jars throughout, as do the Reagan-era lyrics: “Impeach the president / Pullin out the ray gun / Zap the next one / I could be your Shogun / Suckers don’t last a minute / Soft and smooth, I ain’t with it.”

It’s fitting that Chuck labels himself a “Prophet of Rage.” “Hip-hop is my religion and rap music is my military. I’m a serviceman for the culture, for art.”

The message is not always cohesive, though. If anything the music is, and has always been, an example in purposeful political obfuscation. Including voices of everyone from James Brown, to Isaac Hayes, to Malcom X. The measured syncopation of Chuck D and the spastic levity of hype-man Flavor Flav.

Similarly, the “gangster” motif present in “Amerikan Gangster” is paired with Chuck D’s trenchant, aggressive intellectualism. , so he'll talk about “Thievin', robbin', hustlin', pimpin'” in one line and cite Orson Welles elsewhere.

Those tonal shifts along with PE’s esoteric sampling often invites descriptions of its music as avant-garde or high-art rap, classifications Chuck agrees with. “I don’t think low art is something that shouldn’t be included into the form of hip-hop,” he says. “Low art should not always take precedent over what high art does.”

Chuck goes on to describe Public Enemy’s upcoming performance in New Orleans as a “homecoming.” “New Orleans is family,” he says. “New Orleans is the origin of American music.”

His current projects include a solo album, scheduled to drop in July. For Chuck, it’s an effort in establishing relevance. “After 27 years in music you try to find an area you can hone in on,” he says. “Try to find what you want to say and how you want to say it.”

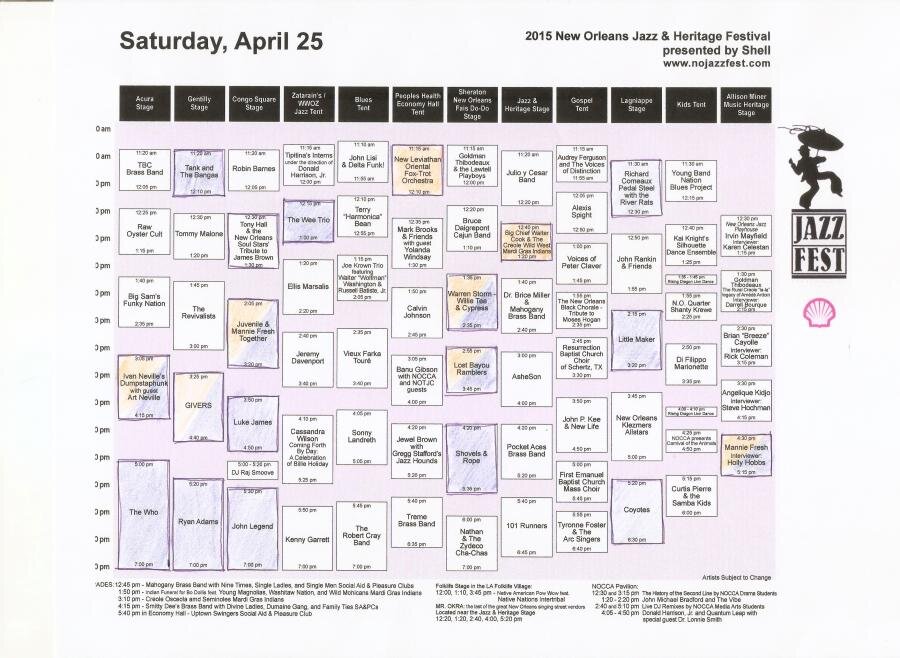

Public Enemy plays Jazz Fest's Congo Square Stage Friday at 5:45 p.m.