James Baldwin Returns from the Grave to Confront White Supremacy Again

The Academy Award nominee "I Am Not Your Negro" powerfully makes a case that shouldn't have to be made in 2017.

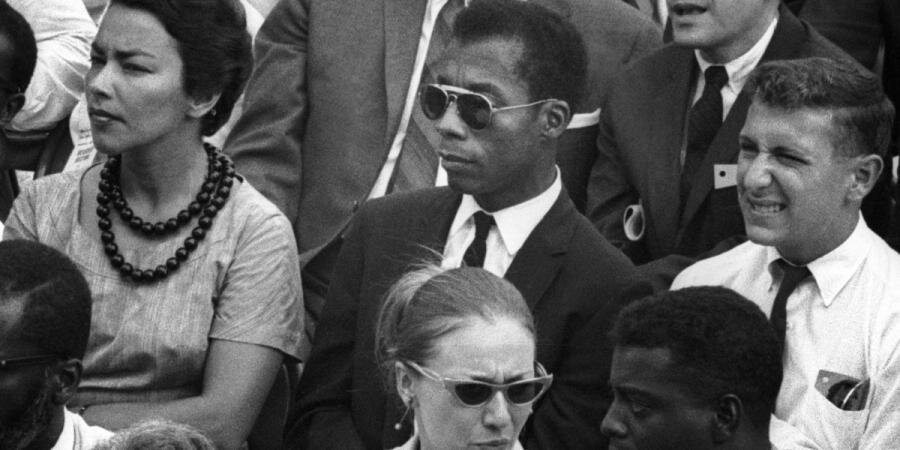

[Updated] Everybody who has written about how I Am Not Your Negro is powerful is right. The film nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary presents the late James Baldwin speaking on writing on race, African-American history and American history, and his eloquence and incisiveness come with clear, dramatic weight.

Addressing the consequences of being black in America could bring out the professor in Barack Obama, but Baldwin doesn’t gear down or moderate his language. When asked in the mid-1960s why black people always bring conversations back to race, Baldwin said, “Once you turn you back on this society, you may die.” In this moment and throughout the film, he speaks like a man who knows he could be shot at any moment, and that knowledge gives him a tangible mix of courage, fear, and sense of purpose.

In the film by Raoul Peck that opens today in New Orleans at The Broad Theater, Samuel L. Jackson reads from an unfinished Baldwin manuscript titled Remember This House, and he shows great restraint as he resists the temptation to go Sam Jackson all over it and instead lets Baldwin’s writing be quietly but unquestionably moving. It’s not obvious the voice is even Jackson’s for much of the film, and while he’s not impersonating Baldwin, you can hear a clear relationship between the two voices fairly quickly.

Peck depicts Baldwin talking ostensibly about Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evans, who were the subjects of Remember This House, but really, Baldwin walks through the 20th and 21st centuries with thoughts on the place of African Americans in the U.S. that are as applicable now as they were then. Color footage of Ferguson and police violence today are shuffled in neither imperceptibly nor showily because Peck doesn’t want to step on the point or emphasize his own filmic slight of hand. Such footage shows up as if it was the obvious, logical next thought, and of course it is.

The film is as much about Baldwin as race, and Peck presents him like many cultural commentators today—someone with enough history to be taken seriously, and with sufficiently culture and pop culture savvy to recognize the insights we can glean by reading the tea leaves of the marketplace and the entertainment industry. Unlike talking heads today, Baldwin has a palpable anger on low simmer each time he’s on television, which makes him a compelling but slightly awkward figure each time he’s on screen. If he were alive today, he wouldn’t be a talking head on speed dial at the cable news networks, but he'd be good television each time he got the call.

While watching I Am Not Your Negro though, it was impossible not to notice that we're having the exact same conversations right now that we had then, and how little has changed. I was thinking about writer David Dennis being flamed by Fox News and its readers for their deliberately obtuse, headline-only reading of his argument that Tom Brady’s MAGA hat makes him more un-American than Colin Kaepernick kneeling in peaceful protest against injustice. I was thinking about Trump supporters taunting Samantha Bee’s Full Frontal staff at the inauguration, and how their seemingly good-natured ribbing echoed the smiling faces of teens holding up protest signs as Dorothy Counts tried to enter Harry Harding High in Charlotte, North Carolina. More than 50 years have passed, and generations of Americans don't seem even curious enough to look into what all that unrest is about. They may not be racist, but in the last election they didn't see racism as a disqualifying trait.

Baldwin talks about white privilege and white supremacy with such clarity that at one point, I had to stop pausing and rewinding the film and adding quotes to my notes. I had plenty, none of which were going to have as much power in my story as they do coming from Baldwin or Jackson. But do we really need to be reminded in 2017 that blacks have to prove themselves worthy of equality daily, which is not a burden white people face? Is it really so hard to accept that generations before us made the system work better and more easily for white people than for blacks? (If it is, viewers would do well to stay away from the Oscars’ Best Documentary category this year, which also includes the brilliant OJ: Made in America and Ava Duvernay’s 13th, which links the mass incarceration of blacks to slavery.)

A.O. Scott reviewed I Am Not Your Negro in Thursday’s New York Times and declared it “life-changing.” Peck’s film and Baldwin's writing have the power to be, but that's cold comfort since the people who most need to see it aren't likely to take time off from prepping for their Super Bowl party to get out and see it. Still, the story of the next four years on the left will likely be one of small acts of resistance, and seeing a good movie is one of the less painful ways to take part in one.

Want more conventional reviews? Try Jordan Hoffman's in The Guardian, Noel Murray's at The AV Club, and David Edelstein's at Vulture.com in addition to A.O. Scott's, which I linked to earlier.

Updated February 6, 10:25 a.m.

I updated the story to include links to other reviews.