From the Drawing Rooms to the Rice Fields

His research into the folk songs of South Louisiana led Joshua Caffery to some unlikely origins.

The music business has its ways of directing people down more fitting paths. Joshua Caffery remembers a reality check moment from his days with The Red Stick Ramblers, when they played a sold-out CD-release show at Grant Street Dance Hall in Lafayette, then performed to two friends the next night at the Hi-Ho Lounge here in New Orleans. A marriage and a Masters Degree gave him an occasion to reconsider if the touring band life was for him, and he decided no. He didn’t leave music, though. He was interested in the roots of Cajun music while in the Ramblers and Feufollet, and it was during that time that he first heard some of Alan Lomax’s field recordings from 1934 in French Louisiana.

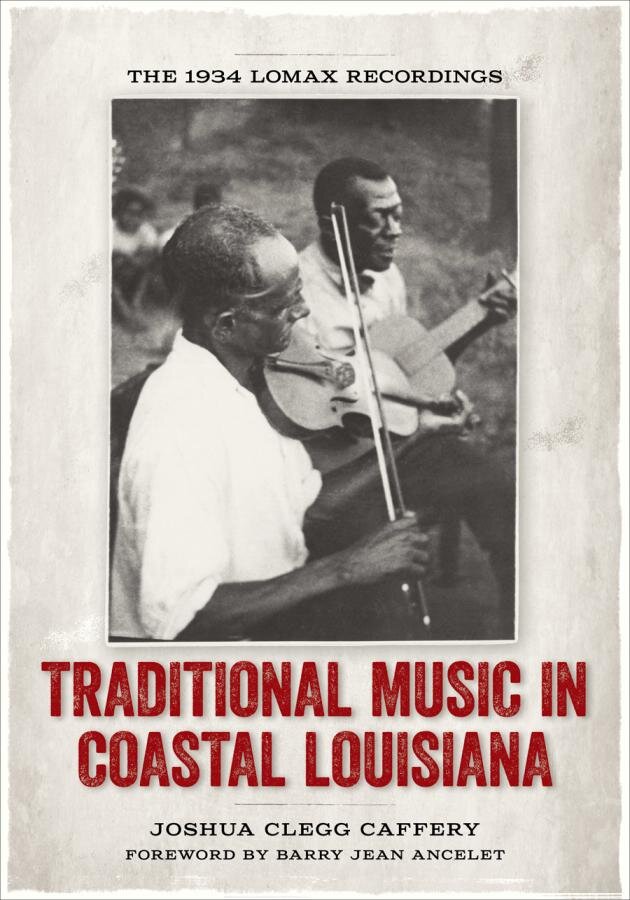

“They represented for me the really old stratum of traditional music in the area,” he says by phone from a building in the Library of Congress. Today, he’s an Alan Lomax fellow in Folklife Studies and working on a website collecting the Lomax field recordings from 1934. His new book Traditional Music in Coastal Louisiana pulls together his research on them, and he’ll be at the Historic New Orleans Collection Saturday from 2 to 4 p.m. to talk and sign copies of his book.

His research into the Lomax recordings became more systematic when he had an assistantship at University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He worked in its Archives of Cajun and Creole Folklore, where he discovered how little had been done with the Lomax recordings. The archive didn’t have all of the recordings, so he worked to complete its collection, including the numerous songs sung in English. In his book, he provides brief biographical notes where possible about the singers, then transcribes the lyrics, translates them if necessary, and examines them for hints of their origins and how the songs changed in South Louisiana.

The songs made it clear for Caffery that South Louisiana was not as culturally isolated as we have typically thought. The insular nature of the culture and the ability of older Cajun and zydeco sounds to continue to present times has led people to assume that was a result of a culture that didn’t have to assimilate or adapt to other cultures.

“They were in contact with cosmopolitan popular culture of the 19th Century and early 20th Century,” Caffery says. “There are all these songs that show up in popular song collections, but also light opera - songs that would have been sung in drawing rooms in France by aristocrats.” Figuring out how they got to Louisiana took some detective work. He found some songs in Canadian songbooks that didn’t exist in French songbooks, so Caffery could infer that some came as part of the Acadian migration. A family that moved to New Iberia from the Alsace-Lorraine region in France sang really old songs with little change from the way they were sung in northern France. “The great mystery is how did these two or three new traditions make it,” he says.

Those “new traditions” are Cajun and zydeco, which are less represented in the Lomax recordings, largely because they were commercially recorded. Alan Lomax and his father John dismissed the bands as “accordion orchestras,” and were searching for what they considered to be real musical expressions from the people. “John saw himself as more of a ballad scholar,” Caffery says. “He was interested in the idea of an American ballad, seeing African Americans as a primitive folk in the manner of European peasantry that would constitute an organic poetic foundation for American culture. Alan Lomax had a more ecumenical vision. He saw it as more polyvalent, that there were many different traditions going on.”

Traditional Music in Coastal Louisiana isn’t Caffery’s first visitation to this music. In 2006, he produced Allons Boire un Coup, a collection of French drinking songs performed by members of the young, traditional music scene in Lafayette that included The Red Stick Ramblers, Feufollet, The Pine Leaf Boys, The Lost Bayou Ramblers and The Figs. While working on Traditional Music in Coastal Louisiana, he discovered that drinking was added to a number of the songs - “I think drinking songs are just popular in French traditional singing” - and when they cut the tracks for the album, it was sometimes at the end of a night out.

“My hope was to try to capture those musicians at their most playful and natural state,” he says. “We had Chris Segura of Feufollet’s house set up like a studio, and whoever we could entice to come by came by. We built it organically around that set-up. It was basically, Come over, have a drink. and we’ll try a couple of songs and see what we can get.” The album is less formal a study than Traditional Music in Coastal Louisiana, but it also had a more ramshackle origins. “My inspiration for that was The Basement Tapes. It sounded like they got a bunch of people together and played a lot of music for a couple of weeks. I wanted that spontaneous feel.”

The book has its personal moments as well. Caffery explores at length the ballad “Batson,” a 38-verse song that tells the story of a brutal family murder in Lake Charles, and the arrest and hanging of Ed Batson for the killing. “A counter-story emerged that he really didn’t do it,” Caffery says, and that’s the story the song tells. While researching the case and its relationship to the song, he found pictures of the sheriff and deputy. “I called my wife into the room to see the picture and her mouth dropped open. I know that man, she said. It turns out her great-great grandfather was the deputy,” he says. “In the song he was a brute who slaps Batson around. In reality, he was a hero and Batson was likely the murderer.”

Caffery will be at the Historic New Orleans Collection at 533 Royal St. from 2 to 4 p.m.