Bobby Z Recalls The Evolution of The Revolution

Prince's drummer remembers how Prince's band came together before it plays The Joy Theater Thursday night.

Bobby Z’s pride in The Revolution is as obvious in conversation as it is justified. Prince had many bands, but The Revolution was the band. Prince’s “last band,” Z—Robert Rivkin—said in an interview, and the thought rings true. Prince may have played with New Power Generation and steady groups of musicians after The Revolution, but those musicians all signed on to play with an international star. Members of The Revolution signed on with a guy who had more talent than buzz and more buzz than sales. And, they grew together. The band found its personality as Prince became better able to express his. He’d play with a lot of great musicians and make great music after he disbanded The Revolution in 1986, but his music would never cross musical genres so easily again. Dirty Mind, Controversy, 1999, Purple Rain, Around the World in a Day, and Parade realized Prince’s vision of appealing to rock and pop audiences as well as R&B fans. For Purple Rain, he dressed his band in New Romantic finery that had passed its sell-by date with London club kids but was fresh for mainstream America. Prince loved heavy guitars, but he also folded in electropop textures and softer musical influences like The Beatles and Joni Mitchell into his funk. The Revolution brought all that to life.

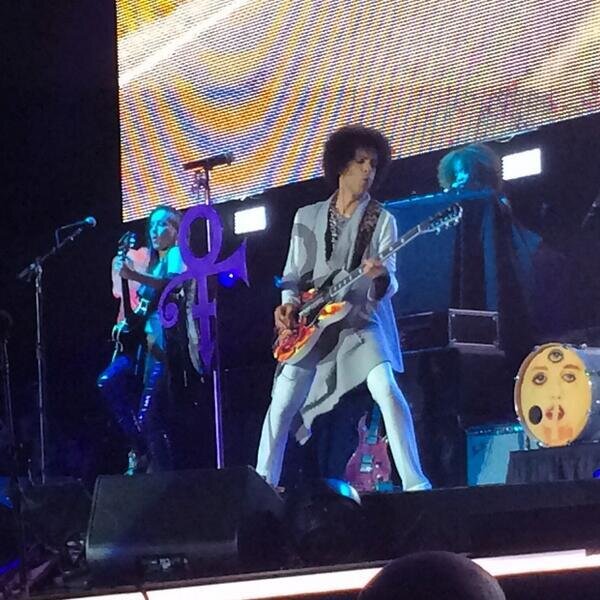

The Revolution plays The Joy Theater Thursday, and drummer Bobby Z/Rivkin has seniority along with keyboard player Matt Fink. They were part of Prince’s first band with Andre Cymone, Dez Dickerson, and keyboard player Gayle Chapman, and they existed to play in concert the songs Prince recorded largely on his own.

Rivkin was an unlikely choice for the drummer. At the time, he was playing with Kevin Odegard, a Minneapolis folkie who’s claim to fame was his participation in the Minnesota sessions for Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks. He saw Prince working in the studio and was blown away by the music and the way he built the songs himself, laying down track after track on his own. “I go, Hey, what's going on in here?” Rivkin told Matthew Singer of Willamette Week. “He looked at me like he just saw Dracula or something. But I won him over with a few jokes.” Rivkin worked for Prince’s first manager, Owen Husney, and he told The Key’s Shaun Brady, “I had to win him over with laughter. During the day I would drive him around and then I would jam with him all night. Eventually I got hired as his drummer, which only took two years of constant playing all night, every night, until I was exhausted. He didn’t need any sleep.”

“Prince wanted a more sophisticated—for lack of a better word—drummer, a busier drummer,” Rivkin says. “Then I think he realized that I had a good versatility to play rock and funk, so I became the Charlie Watts/Ringo Starr model.”

Maybe The Revolution became The Revolution in those endless hours of jamming. It’s when the members learned to play at Prince’s standards, which for Rivkin meant keeping better time. “Prince had perfect time and perfect pitch,” he says. “Nothing got away from him, so you had to stay in your lane and do your job. Even when he was on the speakers 30, 40 feet away, he heard everything.” It was during those jams that they learned to communicate onstage, usually without the audience knowing. “If he ran his hand through his hair, that meant 16 more bars,” Rivkin says. “He was like an NFL quarterback; he had all these audibles. We’d rehearse for hours and hours and hours and could go into any song, any key at any time. They would sound amazingly spontaneous.”

With The Revolution, Prince’s funk sounded similarly natural, but Rivkin contends that his grooves are more eccentric than they seem. “His rhythms aren’t obviously unique until you write them down,” he says. “He liked to put cymbals on the three, fills going into the one, fills on the two—a lot of stuff on the two.” The idea was to create movement toward the next bar, and Prince understood it because he played the drums on his records. “He recorded many of the tracks with drums first,” Rivkin says, then built the tracks from those drums. “It’s like he built a house with the roof first.”

His interest in Bobby Z’s drums extended to their sound, and he worked early on to incorporate electronic elements into the drums. “He was really early—Nostradamus early—on predicting that drums would be played electronically,” Rivkin says. “He pushed me and my techs to get the Linn LM-1 playable onstage. That had mixed results at first, but nothing stopped him from taking risks, even onstage.”

Prince - Party Up from R-Nand on Vimeo.

Even though Prince was always Prince, he went through growing pains. Like all young bands, he didn’t always end up in front of the right audience. “Warner Brothers sent us out to play any place that we could play,” Rivkin says. “There was a country bar in Texas that tried to have a funk night, and that didn’t work so well.” The pinnacle of that came in 1981 when Prince opened for The Rolling Stones at the L.A. Coliseum along with The J. Geils Band and George Thorogood and the Destroyers. The Stones fans were notoriously impatient with opening acts, and even booed The Meters on another tour. That day, the audience otherwise there for an afternoon of white blues rock didn’t know what to do with a petite black man in heels, stockings, bikini bottoms and a trench coat. With meatheaded predictability, the fans catcalled Prince with homophobic slurs.

“He was looking to Europe at Adam and The Ants and Steve Strange and all the things happening over there with music as a liberating form,” Rivkin says. “It was a shock to him that The Rolling Stones fans didn’t get it. They probably became Prince fans later, but the Dirty Mind outfit of trench coat and bikini was a little much for them.”

To see what the Stones fans, watch Prince perform “Partyup” on Saturday Night Live earlier that year. The performance came late in the show on a side stage in a time slot often reserved for cultural sideshows, and really, nothing sounded or looked like Prince at the time. The funk was almost Devo-like in its mechanical nature, so much so that Fink took a break from his keyboard duties to dance The Robot. The show looked like an arena band crammed into bar band space, and each time Brown Mark and Prince spun onstage, they tilted their guitar necks up to avoid hitting each other. Prince’s effortless shift from singing about the timeless desire to party to the coda—“Gonna have to fight your own damn war / ‘cause we don’t wanna fight no more!”—came out of nowhere for those who were hearing him for the first time, and he, Brown Mark and Dez Dickerson looked like perverts in trench coats. The band ended the song by abruptly running at the camera and past it, leaving the stage suddenly and awkwardly bare.

You can understand audiences being confused. Prince almost predicted the slurs yelled at him with Controversy, the album he released before the Stones show. “Am I straight or gay?” he asked in the title track for the thousands in attendance and millions listening at home.

Maybe The Revolution really became The Revolution “when everybody wanted to be there,” Rivkin says. Gayle Chapman left in 1980 because she was felt like whatever she did was going to exist in Prince’s shadow, and it didn’t help that the Dirty Mind tour and its emphasis on sexuality was at odds with her spirituality. André Cymone speculated that making out onstage every night of the tour with Prince during “Head” didn’t help. Cymone left after recording Dirty Mind because he always saw himself as a solo artist, and he knew the best he’d ever manage in Prince’s band was to be George Harrison to Prince’s Lennon and McCartney. Dickerson had his own spiritual epiphany during the Christmas break of the 1980 Dirty Mind tour, which made staying with Prince for three more years difficult. He finally gave his notice after the 1999 tour and was replaced by Wendy Melvoin.

Rivkin points to Melvoin as a possible true starting place for The Revolution. “We’re lifers, and that definitely makes a band more cohesive because we’re committed to it,” he says. “That helps a band grow.”

Maybe The Revolution became The Revolution with the release of 1999. That was the first Prince album to mention the band on the cover, though the liner notes point out that “All music & voices by Prince except where indicated.” The band members are thanked and they appear in a photo for one of the two discs. The photo on the other sleeve is of a naked Prince in bed with paper, water colors, neon art on the wall and floor, and the sheets down at his butt.

For many, The Revolution became The Revolution with Purple Rain. The movie meant that people knew what they looked like and knew their names. The concert footage also let fans see them in ways they’d never been seen before, particularly Melvoin, who emerged as Prince’s onstage foil. On screen depiction of the writing of “Purple Rain” even had a nugget of truth in it as it showed the song to be more of a band creation than songs had been in the past. Melvoin told Spin’s Brian Rafferty that for the song, “Prince came in with the melody and the words and an idea of what the verses were like. I came up with the opening chords, and everybody started playing their parts.”

To learn to be themselves on screen, the members of The Revolution and The Time had to take acting classes and dance classes, and they took them with the lack of seriousness you’d expect. “We ended up just doing Jane Fonda’s workout every day because the teacher got so fed up with our class clowning,” he says. Nonetheless, “We were camera-ready after that.”

Ironically, Purple Rain was also the beginning of the end of The Revolution. Its success opened doors for Prince, who was ambitious with workaholic tendencies on his own before a world of possibilities rolled out in front of him. “He became a superstar,” Rivkin says. “He was pulled in a million directions. He didn’t stop recording. Before we went on tour for Purple Rain, Around the World in a Day was already in the can. He just couldn’t stop, and he had so many different projects. He was consumed with being a superstar.”

“He became more of a satellite,” Lisa Coleman told Spin. “It hurt our feelings. He used to travel with us on the same bus, but then he got his own. He would always be escorted ahead of us in his own car, and we were left behind. He had his big house, and when he got the guard at the gate, it was, Wow, dude. It’s me. I did your laundry. I lived with him for a while in his house — I’d fix him a sandwich or we’d do laundry together.”

The Purple Rain tour changed everything in much the same way the movie did. It was Prince’s biggest tour to that point as well as his biggest production. He made new demands on The Revolution including synchronized dance moves for the whole band including Coleman, Fink and Rivkin, even though they were behind keyboards and drum kits. The movie’s success meant that fans knew their names, and the attention forced a flight of bodyguards to be added to the entourage. Not only did the band not travel in the same bus as Prince, but they didn’t travel with each other. Melvoin and Coleman had a bus to themselves as well.

The long tour was at odds with Prince’s restless creativity, and at first he tried to keep it fresh by changing up arrangements during three-hour soundchecks. Eventually, he started to augment The Revolution with additional players including Sheila E., sax player Eric Leeds, dancer Jerome Benton and Suzanne Melvoin, Wendy’s twin sister and Prince’s girlfriend at the time. That lineup made “Baby I’m a Star” a showstopper—“almost a show on its own,” Rivkin says.

“Keeping up with Prince during ‘Baby I’m a Star’ was kind of crazy. It turned into Simon Says with the horn punches and the stops on the one, but the energy it created put him in another space, which took the audience and the band to another level.”

The end of The Revolution was and wasn’t a surprise. “I’d known him my entire adult life, but he’d become Prince where before he was just Prince,” Rivkin says. After 1986’s Parade tour, Rivkin learned that he was being replaced by Sheila E. He understood that Prince felt like he’d gone as far as he was going to go with a funk/rock/new wave thing and was moving in a more fusion/funk direction and that the change made musical sense. Still, his diplomacy when remembering the change says the moment wasn’t painless. “I fought off every drummer in town twice to get the job. To hold on to it for 11 years—I was fine,” he says.

Coleman told Spin that her firing was oddly elaborate. “He brought Wendy and me to his house for dinner,” she said. “We always called it the ‘paper-wrapped chicken dinner,’ because it was wrapped in pink slips. We’d be here in L.A. and he’d send us tapes with a piano and vocal, just an idea, and then we’d produce it. We would do all the instruments and background vocals. He felt like, I need to take it back and do it all myself again. I’m losing touch with myself. So unfortunately, I’m going to let you go, because you’re doing everything.”

Despite the unceremonious ends of their tenures with Prince, eventually the members of The Revolution took on alumni status and were part of the extended Prince family if not the band. “He used to call us Mt. Rushmore,” Rivkin says. “He understood that the celluloid version of the band etched us in stone.” The chemistry that they developed never went away, nor did the special bond of sharing an experience as remarkable as playing with Prince at that time. “Chemistry is an intangible thing. We love to play off each other and have a way to be tight and be incredibly proud of each other. The glow never went away.”

“I had three relationships with him—I was a friend first, then a professional one for many years, then a friend later. He knew I was a loyal soldier,” Rivkin says. Even when Prince was recording with other lineups, he’d play songs for Rivkin to get his response. “He’d always get the truth from me, but I was always taken by his ability and songwriting and mastery of the craft. I marvel at it to this day.”