Aspiration and Prerogatives at Essence

Notes on Janelle Monáe, Bobby Brown and more from last weekend's Essence Music Festival.

The Essence Music Festival is narrowcasting at its finest. The event not only speaks first to African-American women, but those who believe in the classic R&B verities. That has left festival organizers with the slimmest of Rolodexes from which to select main stage artists, as the number of year-to-year repeats illustrates. Nonetheless, Charlie Wilson virtually filled the Superdome Saturday night, Beyoncé gave Essence a rare sell-out Sunday, and the weekend's attendance of more than 540,000 made it the biggest Essence Fest ever. For most of the weekend, little cutting edge went on musically or visually, but it's clear that the festival's target audience is happy that way.

As I observed in my coverage of Essence for USA Today, nobody went wrong by flying the flag for old school. You can see my reports from Friday with Maxwell and Jill Scott, Saturday with Charlie Wilson and New Edition, and Sunday with Beyoncé and Janelle Monáe. Here are notes from the weekend that didn't fit in those pieces.

- There is usually a tension between the superlounges and the main stage, and it was pronounced this year. The implication was that the former featured music that an Essence reader should want to hear, while the main stage presented the music it actually wanted to hear. African vocalist Simphiwe Dana sang to a gathering that didn't have the numbers for a touch football game, and Maya Azucena didn't fare much better. Both drew from deep, valued musical roots, with Azucena's set seemingly from an earlier time (the '90s) and place (England) - a jazzy R&B funk seemingly unmarked by hip-hop. That too seems to be an Essence musical value, one the audience didn't share.

But that tension doesn't mark a disjunction so much as a characteristic. The Essence Music Festival always has an aspirational dimension as it presents models of who African-American women could be. This year, Jill Scott and Beyoncé presented two visions of Black women; in previous years, Mary J. Blige was a third. The superlounge fare is often for the woman who is or would like to be worldly and urbane. And while some artists don't find audiences there, others such as Scotland's Emeli Sande received a hero's welcome.

- Artists are almost always more interested in their newest efforts, but it was startling the degree to which that was the case for Maxwell. He sang the opening "Sumthin' Sumthin'" from 1996's Urban Hang Suite with the fire of a man ordering a pizza. When he teased "Ascension (Don't Ever Worry)" from the same album and the audience responded enthusiastically, he tried to beg off. "That's so old," he said. The set started so poorly that an early attempt at a sing-along got no audible response. None. But when he sang an unreleased new song, "Gods," he found his passion, and it animated the rest of the set and finally kindled a relationship with the crowd.

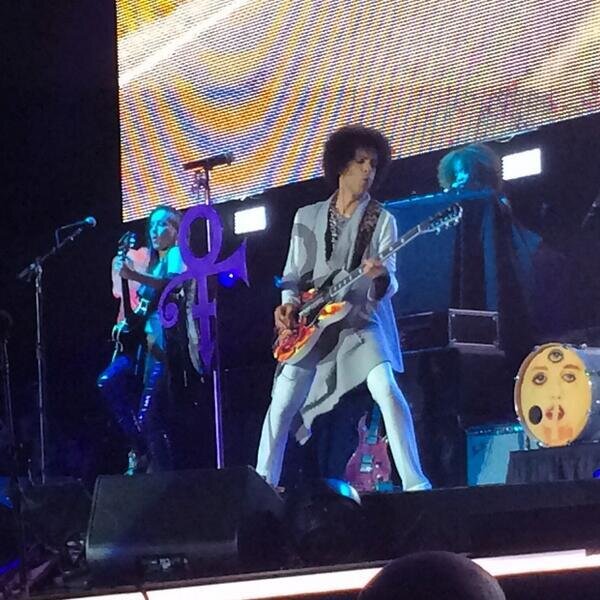

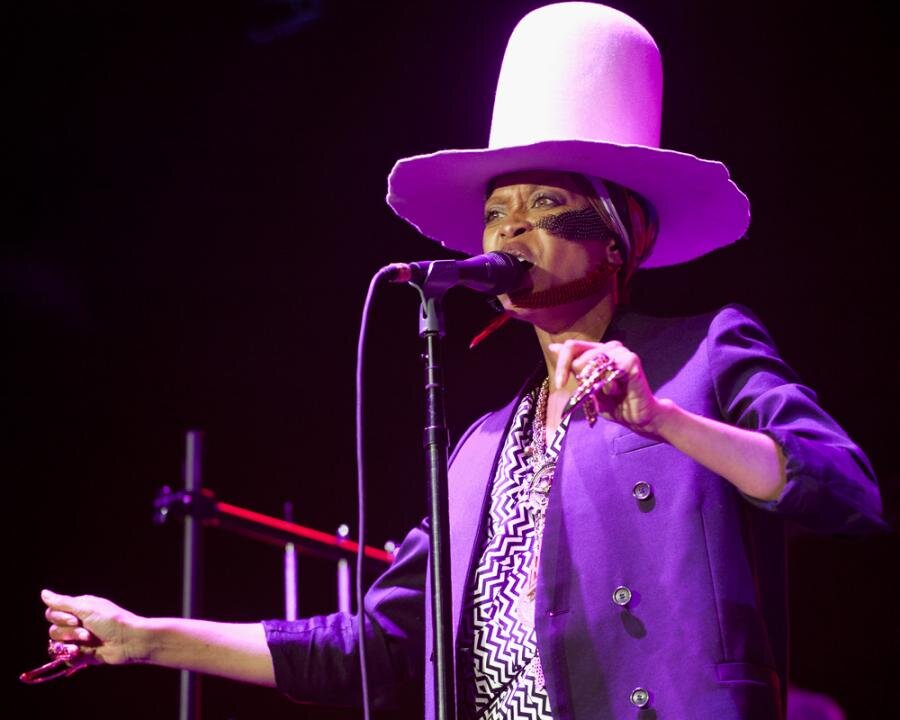

- At this point, Janelle Monáe is more of a presence in the culture than a part of people's CD collections - a critically acclaimed artist and a Cover Girl model, but not someone whose music they know. She enhanced her brand during Essence by curating the Cover Girl Superlounge, including sets Friday and Saturday nights by bands she's producing. Saturday night's set by the Wondaland Arts Society, as she dubbed the collection, felt like a house party for her band and their friends since each act is affiliated with her. The two women who constitute St. Beauty appeared to be her backing vocalists, one guitarist in Deep Cotton is Monáe's guitarist, and Roman GianArthur composed her show's overture.

St. Beauty and the Black rock band Deep Cotton were a little outside of Essence Festival's musical orthodoxy, which tends toward straightforward, unironic musical expressions. If a guy wants to make love, he's likely to sing, "I want to make love to you," not dress it up in metaphor and allusion. Desire is expressed through raw intensity instead of more indirect routes. As such, Monáe and Company were outliers on the weekend, like a Paisley Park if it existed pre-hits. Unlike many of the Paisley Park projects, the Wondaland bands didn't seem like extensions of the leader's ego and had an independent existence. They shared values - all were stylish yet fiercely individual in the ways that mattered - and they were entertaining regardless of Monáe's connection. The three-guitar, downstroke-heavy rock of Deep Cotton might not move me on record, but it was a blast live, and I know I want to hear the voices of the women in St. Beauty again.

- The crowd for New Edition Saturday night still loves Bobby Brown, no matter what. He clearly ran out of gas before the show-closing "Poison." When one member ran down the runway to the far reaches of the audience on the floor, Brown looked like he would follow, then thought better of going all that way and stayed where he was. He skipped the strenuous choreography as well, but he did summon some grit and passion for "My Prerogative," probably more than was seemly.

It's one thing to sing, "Why won't they just let me be?" when you're young, brash, and the price of celebrity is as new to you as celebrity itself. But when you're in your 40s and have had a very public lover's quarrel with drugs and the bottle, you probably shouldn't invest energy in that line because you know the answer. 'I'm leading a tough life' is a hard-sell as subject matter for young singers; claiming you should be able to do what you want is harder for a full grown man since few of us at any age get that license - certainly few in the Superdome. When you've used a reality show about your messy, sad life with Whitney Houston to help stay in the public eye, you can't seriously invest any emotion other than gratitude for the attention you get.

Or, you could be Bobby Brown and give it rage anyway.